Conducting a comprehensive assessment is the foundation of advanced nursing practice and requires competencies in critical thinking and clinical decision-making (Nursing and Midwifery Board of Ireland (NMBI), 2017). An advanced (mental health) nursing practice assessment has been defined by Poulhuis and Grealish (2022) as a: ‘Process by which an (advanced nurse practitioner) engages and interacts with the person and their significant others; collects, selects and weighs information; comes to a contextual understanding of the situation and makes collaborative clinical decisions’.

This definition aligns with the assessment process in advanced nursing practice in paediatric neurodisability, where the collection and interpretation of information informs the formulation of interventions underpinned by the biopsychosocial (BPS) model. The following paper will critically review this model within the context of a strengths-based approach and neurodiversity paradigm, which are core elements of advanced nursing practice in this area. The paper will present an anonymised case study from the author's area of clinical practice, to illustrate the advanced practice skills utilised in the assessment process, from information gathering to the interpretation of data, to collectively inform the case formulation. The clinical recommendations from the case example will be critically reviewed within the context of the current evidence, including an appraisal of behavioural-based interventions. Verbal consent was obtained from the child's parent to write an anonymous paper on their experience and all identifying information about the case has been changed. The paper concludes with a summary of key themes and makes recommendations for future research and practice.

The author is currently employed as an advanced nurse practitioner (ANP) in paediatric neurodisability working in a community setting across several children's disability network teams in Ireland. Like other jurisdictions, advanced practice roles in the Irish healthcare context are developed in response to service need, patient demographics and in the interest of quality (Department of Health, 2019). In Ireland, ANPs are registered with the NMBI and are viewed as senior clinical decision-makers (NMBI, 2017). Although relatively new to the Irish healthcare setting, the ANP role has significantly evolved since its initial inception (Thompson and McNamara, 2021).

In this case example, the ANP in paediatric neurodisability works on a specialist, interdisciplinary team that provides an intensive level of assessment and support to children and young people who present with neurodevelopmental differences and associated emotional regulation needs, from ages 0–18 years, in a community setting. The paper refers to neurodevelopmental disability rather than neurodevelopmental disorders, despite this being the terminology used in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual 5th edition diagnostic criteria (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). The use of the term ‘disorder’ has been criticised for being deficit-focussed and does not acknowledge the disabling impact of socio-environmental factors on a person's needs (Rose, 2022). The author's area of clinical practice is framed within the neurodiversity paradigm, which embraces the range of diversity that exists in neurodevelopment and rejects the view that divergence from the ‘norm’ (neurodivergence) is a pathological disorder requiring ‘fixing’ (Walker, 2021). Language and terminology utilised in the paper is reflective of this.

Overview

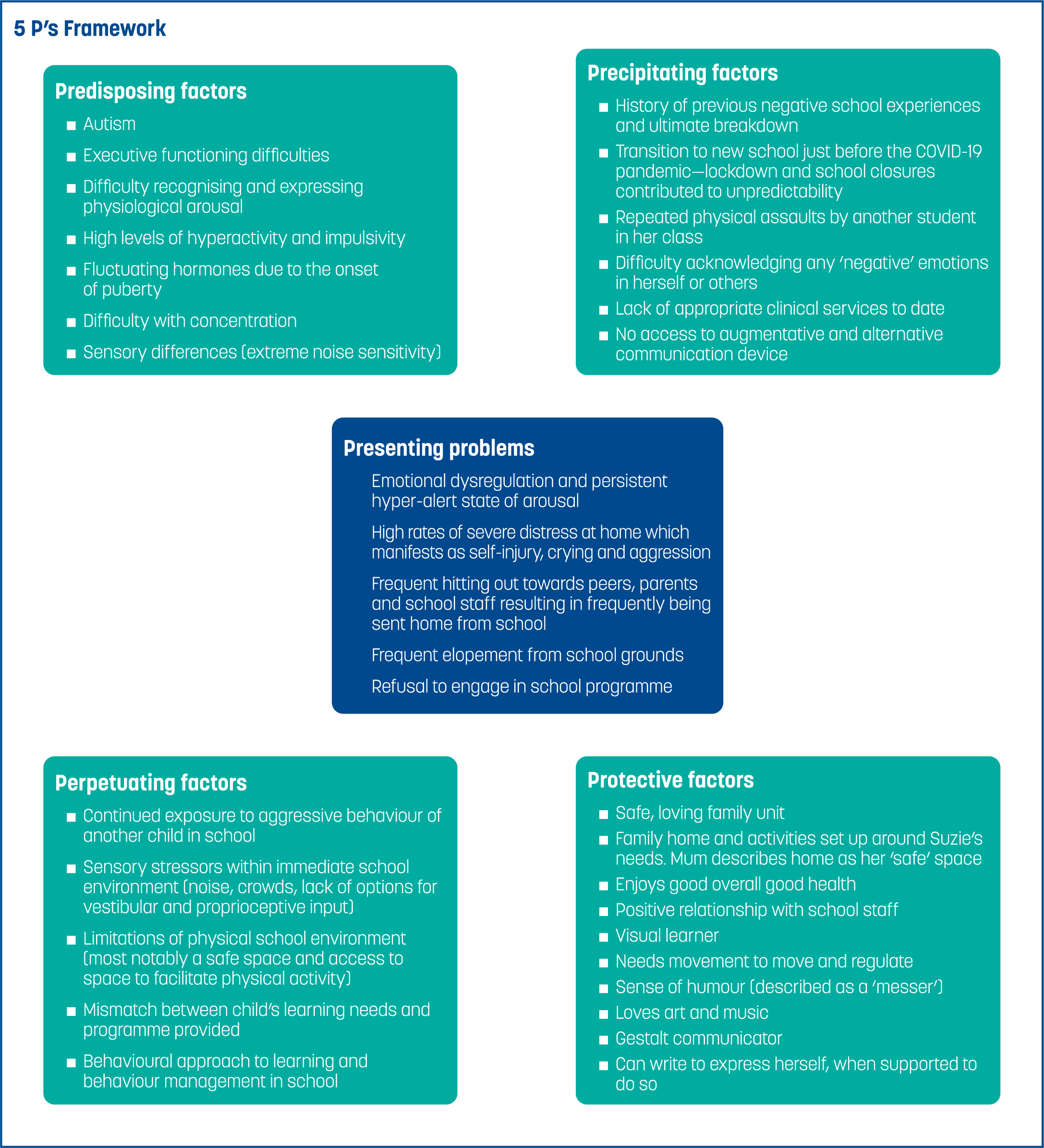

The child, who will be rereferred to under the pseudonym ‘Suzie’, is a 13-year-old autistic girl who receives clinical supports from her local children's disability network team. She was referred to the specialist team for intensive assessment following a request from her mother, due to the presence of significant self-injury, aggression towards others and a deterioration in skills and participation across all environments. Given the complexity of Suzie's presentation, a decision was made to refer her to the ANP. Suzie was at an imminent risk of school breakdown and parental stress levels were reported as extremely high. The ANP coordinated the interdisciplinary team assessment for Suzie, which took a total of 40 hours to complete. It consisted of a comprehensive clinical history with her parents and teacher, direct observations across home and school environments, and the utilising of a standardised questionnaire (the Conners 3) for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) to augment the clinical reasoning process. Assessment data was analysed and interpreted to develop a developmental profile of strengths and needs for Suzie, and an additional diagnosis of ADHD was clinically indicated. The presence of exposure to traumatic events in school made assessment more complex. Case formulation was utilised to develop a support plan which was informed by her many strengths, preferences and individual learning profile.

Theoretical principles underpinning the assessment process

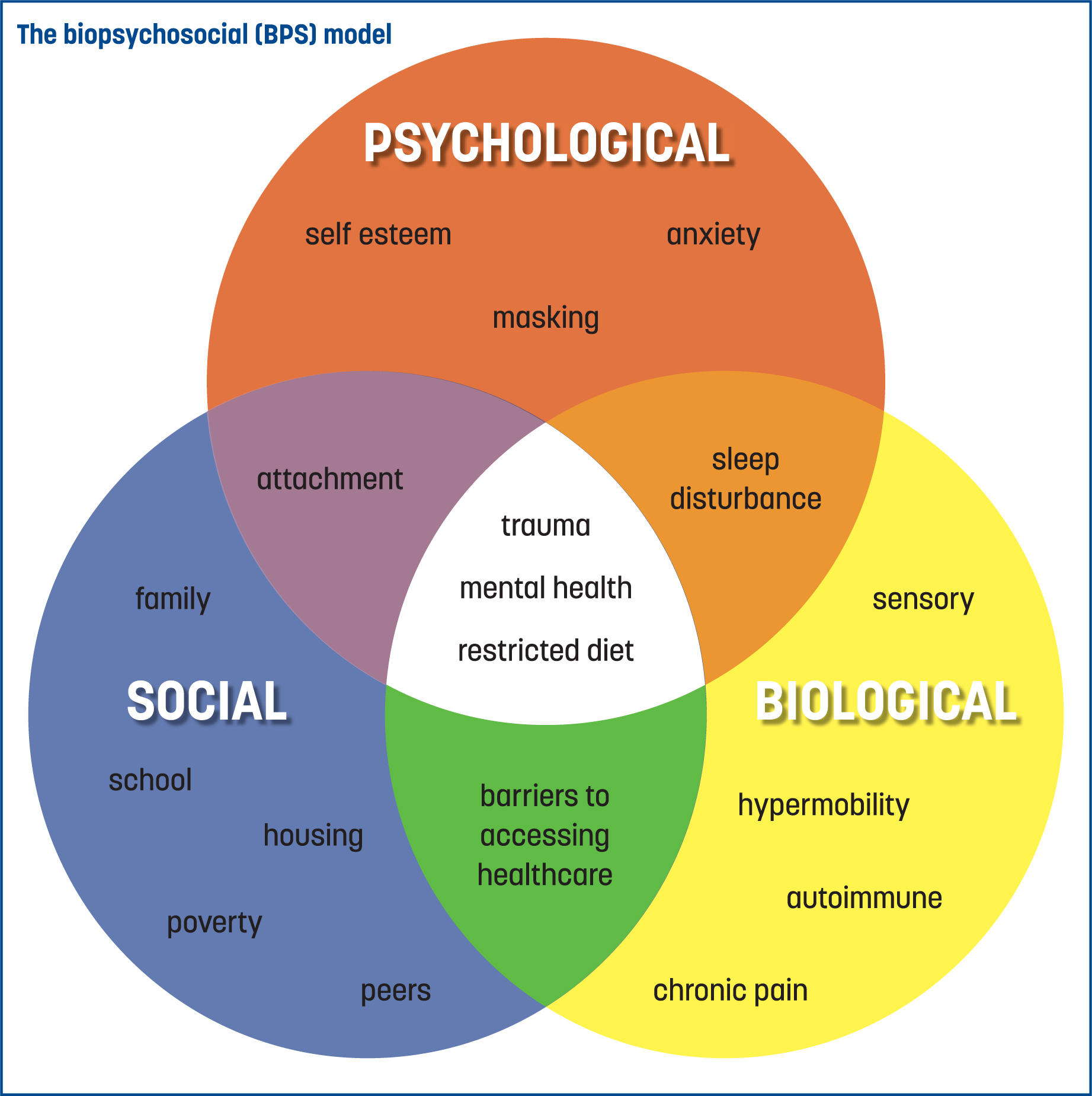

The ANP assessment and practice, in the author's clinical area, has drawn on evidence-based practice (EBP) frameworks from both the disability and mental health fields, as the caseload includes both domains. EBP involves the integration of the best available research with clinical expertise in the context of patient preferences, culture and characteristics (Woods, 2019). The primary core principles underpinning the assessment process for the case example are the BPS model and a strengths-based framework. The BSP model, which was arguably first coined by Roy Grinker in 1952 and then expanded upon by George Engel in 1977, remains relevant to contemporary advanced nursing practice. Engel (1977) proposed an alternative to the dominant medical model of mental illness—one that was based on the interconnection between mind and body, where biological, psychological and socio-environmental factors interact. The model proposes that difficulties experienced by people can be influenced by multiple domains of human experience across different contexts and recognises that the interventions required may be multi-faceted. Underpinned by the BPS model, Suzie's assessment was completed across home, school and community settings; and biological, psychological and socio-environmental factors were considered within the assessment process (Figure 1).

The BSP model was adopted by the World Health Organization (WHO) in 2002. It has subsequently been used to develop guidelines in a national and international context, including the policy framework for service delivery of children's disability network teams in the authors' area of practice (Figure 2) (Health Service Executive, 2022). Despite its widespread use, the BPS model is not without criticisms. According to Ghaemi (2011) physicians who adopt the BPS model are at risk of losing the defined boundaries regarding their expertise and knowledge. As Ghaemi's critique is specific to the medical profession, one could argue that it is an appropriate framework for ANPs in neurodisability, due to the holistic framework underpinning advanced nursing practice and the focus on the interconnection between the body and mind.

A strengths-based approach (SBA) underpins all elements of the author's assessment processes and clinical practice. This approach aims to identify the child's strengths and resources within the assessment, to support the identification of appropriate interventions. Historically, disability and mental illness have both been conceptualised within a medical model and deficits-based framework (Wehmeyer, 2020); the SBA approach provides an alternative. Xie (2013) acknowledges that traditional mental health assessments are designed to determine deficits and essentially pathologise the person, whereas a strengths-based assessment is more comprehensive and is essential to maximising positive outcomes. According to Niemiec and Tomasalo (2023), focusing on strengths and needs within the context of a person's environment is central to the SBA, in order to wholly understand their presenting difficulties. The SBA is appropriately positioned within the neurodiversity paradigm, which respects all forms of neurological diversity and centres neurodivergent voices at the core of the movement (den Houting, 2019).

The concept of neurodiversity has been the subject of considerable debate within the literature. Neurodiversity itself is a biological fact, defined by Walker (2021) as ‘the diversity of human minds, the infinite variation in neurocognitive functioning within our species’. Recognition of this fact has given rise to the neurodiversity paradigm, the philosophical basis for the activism of the neurodiversity movement, which values the range of diversity in human brains and centres around the voices and experiences of neurodivergent people. Critics of the neurodiversity paradigm, such as Jaarsma and Welin (2012), argue that it can only be applied to ‘high functioning’ autistic people. They suggest it diminishes a person's disability or support needs because neurodiversity advocates do not view autism as a disability. In line with this view, some parents of children with significant support needs have claimed that the autistic advocates leading the neurodiversity movement, do not represent more disabled autistic people such as their children. It is clear from such arguments that criticisms of neurodiversity appear to be largely based on misconceptions, and the failure of opponents to acknowledge the authentic inclusion of all neurodivergent voices, including those with the highest support needs, such as Suzie.

Misrepresentation of the neurodiversity movement has resulted in the promotion of ‘neurodiversity lite’ by many services, a term coined by Neumeier (2018) to refer to the superficial appropriation of the neurodiversity language, without genuine application of the concept. Xie (2013) acknowledges the difficulty faced by services to move from pathology-driven models to a strengths-based approach. Suzie's case study provides an example of how employing a strengths-based approach from point of referral, through to assessment, facilitated meaningful goals for her and her family.

Coexistence of autism and other disabilities

The challenge for any clinician assessing and evaluating difficulties arising from neurodevelopmental differences is determining the specific factors that contribute to difficulties being experienced by the child. Co-existence of specific neurodevelopmental disabilities is common and there are many overlapping differences across multiple developmental domains, including communication and language, motor coordination, attention, behaviour, sleep, social relationships and mood (Rutherford and Johnston, 2023), as was the instance in Suzie's case. It has been well established in peer reviewed studies over the last decade that autistic people experience higher rates of physical and mental conditions across multiple body systems, further suggesting that a holistic approach to support is needed. Two systematic literature reviews conducted by Bougeard et al (2021) from the period 2014–2019, which included 13 studies on the prevalence of autism and 33 on co-occurring conditions, found extensive evidence of greater rates of both physical and mental health conditions—including visual/hearing impairments, epilepsy, gastrointestinal disorders, depression, ADHD and anxiety—co-occurring with autism. This evidence has been instrumental in the comprehensive and multi-dimensional approach utilised in the ANP assessment in the author's clinical area; advanced clinical judgement skills are also required to differentiate the overlapping traits across the different domains.

Assessment process and clinical history

An individual approach to each child/young person is essential to obtain information about their biological, psychological and socioenvironmental history, in order to better understand them and their presenting differences. Multiple assessment methods are required to ensure holistic, objective information is gathered. Clinical interviews, observations and questionnaires are methods utilised as standard in both clinical practice and research, within the disability and mental health domains. The clinical history is widely acknowledged as a core element of clinical assessment within multiple frameworks (Douglas et al, 2005). A comprehensive clinical history is an essential component of the advanced practice assessment process and a core skill of the ANP role (Ingram, 2017). In the area of paediatric neurodisability, the clinical history is primarily obtained from parents or guardians, and as developmentally appropriate, with the child or young person. The information gathered is used to develop an in-depth understanding of the child's experience. In Suzie's case, the developmental history was obtained from her parents with some input from her teacher, as she indicated a preference for not engaging in this part of the process. A comprehensive clinical history provides the information needed to formulate a profile of the child's strengths, skills, needs and impairments, identify external factors contributing to current issues and signpost towards additional assessments where indicated, such as specific neurodevelopmental assessments and onward referrals to other clinicians or services.

Observational assessments

Observational assessments were also utilised with Suzie, to gather objective information across different settings. Observational assessments involve obtaining both quantitative and qualitative data through direct observations of a person in natural settings. They are widely used within the education, health and psychological fields, and most often used to obtain information on behaviour, social-emotional functioning, language and skills (Spear-Swerling, 2021). Observational assessment can increase the reliability of informant interviews and ensure objective data is obtained, thus minimising the risk of informant bias (Fix et al, 2022). In clinical practice, the author has found that children tend to present more anxious and dysregulated in a clinical setting. As a result, it can be difficult to obtain an accurate baseline; thus, direct observations in natural settings can often be more beneficial. Direct observations in natural settings of Suzie provided a valuable insight. This approach resulted in objective evidence when there was conflicting information provided by her parents and school staff in informant interviews around her ability to engage in learning tasks and preferred activities.

Standardised rating scales

Questionnaires and rating scales can be used to augment clinical history and physical assessment (Baer and Blais, 2010). There are numerous tools used to generate quantifiable measures across a range of outcomes, including presence, severity, frequency of specific traits, quality of life aspects, health and wellbeing. Tools utilised must have robust validity and reliability; however, they do not replace clinical decision-making of practitioners. In Suzie's case, the clinical history and observations indicated many traits in line with current ADHD diagnostic criteria, consequently the 3rd edition of the Connors questionnaire (2022) was administered to enhance the clinical reasoning process. This is a standardised, psychometric tool that is widely used to support the diagnosis of ADHD in childhood (Conners, 2008) and used consistently in the ANP's area of practice. This tool has been shown to be both a reliable and valid measure of ADHD (Izzo et al, 2019). Although standardised tools can have a place to support clinical reasoning, they very much remain within a deficit framework and can centre around the impact of the person's behaviour on others, rather than on the lived experience of the neurodivergent person (Rutherford and Johnston, 2023). Despite some progress by individual clinicians and service providers, the clinical application of the neurodiversity paradigm has not resulted in positive changes to standardised assessment tools or diagnostic criteria such as the DSM-5 (American Psychiatric Association, 2013).

Case formulation

Diagnosis alone does not incorporate the complexity of individual cases, nor does it provide information regarding the cause of a person's current presentation nor the impact on daily functioning (MacNeil et al, 2012). Case formulation has gained much interest in recent years and transcends diagnosis. It incorporates an assessment of presenting biopsychosocial factors, the maintenance factors and an intervention plan achieved through a collaborative approach between the child/young person, their family and the clinician (Rainforth and Laurenson, 2014). The Five P's framework (MacNeil et al, 2012) is a formulation tool that was utilised to assist with the assessment information for Suzie. The depth of this model aligns with the ethos and skill set of an ANP. The five key areas in this model are the following:

Comprehensive case formulation is essential to clinical reasoning in advanced practice, to inform an appropriate, evidence-based support plan. Diagnosis alone does not provide information about specific support needs. Given the overlapping traits across different neurodevelopmental disabilities, such as autism, ADHD and mental health issues, it is necessary to have an advanced level of understanding about the overlaps and distinctions in order to inform clinical reasoning and the differential diagnosis. Since the launch of the DSM-5 in 2013, that there has been an acknowledgement that autism and ADHD can coexist in the same individual. Prior to this, dual diagnosis was not permitted and the two were considered mutually exclusive (American Psychiatric Association, 2000). Many studies have been conducted to further explore the prevalence and commonalities of both diagnoses. Two recent epidemiological meta-analyses have shown that the number of children and adolescents with ADHD who meet the criteria for autism ranges from 12–40% (Hollingdale et al, 2020); between 2–86% of autistic individuals also meet the diagnostic criteria for ADHD (Lai et al, 2019). This emerging evidence is significant in terms of gaining a better understanding of the caseload and should also be a consideration in the development of services for neurodivergent children.

Overlapping symptoms of ADHD and trauma further complicates differential diagnosis. Young children who experience trauma may have symptoms of hyperactivity and difficulties with concentration that resemble ADHD. Physical and psychological trauma can make children feel agitated, nervous and on hyper-alert, which can be mistaken for hyperactivity and inattention (Siegfried and Blackshier, 2016). This consideration was particularly important in this case, as Suzie had experienced trauma in the form of physical aggression from another student in school. Observational assessment clearly indicated a heightened level of physiological arousal when she came into any contact with this student, which manifested as restlessness, hyperkinesis and difficulty attending to tasks. This highlights the need for an in-depth clinical history, which includes the developmental context of the onset of these traits.

Physical examination

Despite the high rates of co-occurring physical conditions in autistic people, they can experience significant barriers to accessing appropriate healthcare. A self-report survey of over 500 autistic adults and 157 non-autistic adults by Doherty et al (2022) found that 80% of autistic adults faced difficulty accessing a GP. These difficulties have been affirmed in clinical practice and, in the author's clinical experience, tolerating even basic physical examinations can be difficult and traumatic for many autistic children. In relation to this case example, Suzie's mother reports that she has not attended any medical appointment in years and previous experiences have been very stressful for her.

Acknowledging the overarching aim of the ANP in neurodisability is a biopsychosocial assessment, the need for physical assessment is crucial, and an area that requires systematic development within the sector. Phelan and Blair (2018) recommend that physical health assessments should be regarded as a continuous process throughout a person's contact with services. This consideration would be a core feature in the future expansion of the ANP service through the establishment of local ANP-led specialist pathways and the development of integrated care pathways with primary and acute services.

Clinical recommendations

Mental health and emotional regulation difficulties can occur because of a mismatch between a child's support needs arising from neurodevelopmental differences, and how these needs are understood and supported by those around them. The clinical recommendations for Suzie comprised of a range of trauma-informed, non-pharmacological interventions based on current best practice within a neurodiversity-affirmative model. The Therapist Neurodiversity Collective (2023) advise that neurodiversity-affirming practices are non-behavioural, ‘trauma-informed and respectful of sensory systems, diversity in social intelligence, autistic learning styles including monotropic interest systems’. There is significant evidence indicating that applied behaviour analysis (ABA) is ineffective, unethical and a violation of human rights. Many autistic self-advocates and academics have indicated that it promotes masking and causes trauma, and this has been reflected in the evidence such as the large survey of 460 children and adults conducted by Kupferstein (2018), which found that almost half of the respondents exposed to ABA met the diagnostic criteria for post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

Positive behaviour support (PBS) is frequently recommended as a ‘softer’ alternative to ABA; it has been widely adopted as the ‘intervention’ of choice for supporting autistic children with distressed behaviours across a range of educational, health and social care organisations. Within an Irish context, the provision of PBS is mandated in the Health Act (2007), and forms part of the Health Information and Quality Authority (HIQA) standards (2013) for evaluating residential service provision for children and adults. Despite its widespread use, there are ongoing concerns with regards to its impact and efficacy, and it has been the topic of much debate within the clinical and academic arena. A systematic review by Simler et al (2019) concluded that there is insufficient high-quality empirical evidence to support the efficacy of PBS across a range of domains, including improving quality of life and reducing restrictive practices. Similarly, Gore et al (2022) acknowledges the lack of rigorous evaluation studies for PBS in the UK. Despite this, they maintain their stance that it is an appropriate framework for supporting people with intellectual disabilities, but concede it is not for people who ‘identify as neurodivergent’ with no intellectual disability. The National Joint Committee on Disability Matters in Ireland (2023) acknowledges that behaviourist approaches such as ABA and PBS are founded on modifying people's behaviour to align with more neurotypical ways of behaving and communicating, and therefore cannot uphold the United Nations Convention for the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (UNCRPD) principles of autonomy, dignity, right to identity and freedom from non-consensual or degrading treatment. Despite the multitude of concerns, PBS remains embedded in educational, health and social care settings, both in Ireland and internationally.

One of the primary aims of Suzie's support plan was to provide an alternative to the dominant behavioural approach; recommendations included a range of strategies to accommodate her learning, sensory and communication needs, reduce environmental stressors, develop her emotional regulation skills from an interoception perspective and ensure that the school team utilised a child-centred, low arousal approach to co-regulation and managing her distress when it occurred. It contained a range of trauma-informed strategies to promote her sense of security and minimise her experience of hypervigilance within the school environment. The programme was underpinned by her strengths and designed to support her to reach her full learning potential, rather than encouraging compliance through extrinsic reinforcement, which held little value in supporting any meaningful learning for her, and ultimately exacerbated her anxiety. Training in the areas of autism and ADHD was provided to the school by the interdisciplinary team, to ensure successful implementation of the clinical recommendations. Suzie's hyper-arousal and associated distressed behaviours significantly improved, when she was facilitated to have greater control over her learning programme, within a safe environment.

Despite meeting the diagnostic criteria for ADHD, Suzie's parents choose not to pursue pharmacological interventions and declined an onward referral to their local child and adolescent mental health (CAMHs) team. A small-scale qualitative study by Flood et al (2019) indicated that the decision by parents to commence ADHD medication is difficult and brings on feelings of powerlessness and guilt; Suzie's parents were reluctant to explore this treatment avenue for her. This reflects the concept of shared decision-making, which was central to the development of interventions whereby both Suzie and her parent's preferences and values were considered.

The assessment process and case formulation for Suzie was developed from an interdisciplinary perspective, with a collaborative approach taken by the team. Interdisciplinary team-working is a core element of children's disability teams; evidence suggests that when interprofessional healthcare teams practice collaboratively, it can improve the delivery of person-centred care and lead to better outcomes (Sangaleti et al, 2017). In Suzie's case, the interdisciplinary team included the ANP, clinical psychologist, occupational therapist, speech and language therapist, and clinical nurse specialist. Farrell et al (2015) suggest that ANPs are in a unique position to assume a key role in the development of interprofessional collaboration in practice and decrease the often-fragmented approach of the current healthcare system.

Conclusion

This case example demonstrates the comprehensive nature of the ANP assessment process, highlighting the unique position of the ANP in paediatric neurodisability to go beyond diagnosis, critically review all the information to inform clinical decision-making, and formulate interventions in line with the person's strengths and needs across multiple domains. Case formulation indicated that despite Suzie's history of trauma, she meets the diagnostic criteria for both autism and ADHD. This conclusion was reached following an in-depth, intensive assessment that took approximately 40 hours to complete. This highlights the complexity of assessment in the field of neurodevelopmental disabilities given the significant overlap of traits across the different diagnoses, and the role of the ANP in the assessment process. Suzie has made significant progress since then, enjoying a more meaningful school programme, with greater control and autonomy over her day. She has been provided with her own space, which has significantly supported a reduction in hypervigilance, and has been provided with a communication device to express her needs. She has still not managed to have a physical examination or accessed her GP; however, this area of need is currently being addressed as a wider organisational issue and there is a plan for establishing pathways to increase accessibility to healthcare for autistic children.

A systematic, comprehensive BPS assessment, underpinned by a strengths-based approach within a neurodiversity-affirmative paradigm, is central to clinical reasoning and the identification of appropriate interventions within the area of advanced nursing practice in paediatric neurodisability. Case formulation is a complex but core skill of the ANP in this area, and bridges assessment and treatment. A robust and extensive clinical history is key to gathering sufficient information. There can be significant difficulties with aspects of the physical assessment for a large cohort of this population, as was the case with Suzie, which poses a considerable clinical need. This suggests the need for the development of more specialist pathways to facilitate close collaboration with other clinicians, such as GPs and paediatricians, to share information and utilise a collaborative approach to assessing the often-complex health needs of this caseload in a dynamic way.

A literature review for this paper confirmed the distinct lack of evidence in relation to advanced nursing practice within the paediatric neurodisability field; this area warrants considerable development, both in practice and within the research sphere. While the neurodiversity paradigm underpins ANP practice, it is essential that it also influences any future research undertaken to ensure that the lived experience of neurodivergent people are at the core of any research in this area. As the establishment of the ANP role in paediatric neurodisability is a recent development, there is significant scope to align service development and future research within the neurodiversity paradigm and drive meaningful change in existing services.