Advanced clinical practitioners (ACPs) are currently embedded in an ACP-led Ambulatory Emergency Care (AEC) clinic. They work under a designated acute medicine consultant responsible for the overall care of the clinic's patients.

The ACPs triage, undertake subjective and objective examination, diagnose and implement management plans. The patient is then reassessed by a consultant to ensure that the diagnosis and management plan is optimal and aligned to best practice. There is an increasing demand for patients to be redirected from the emergency department into the AEC, alongside more GP referrals into the clinic. Increased winter pressures and the impact of COVID-19 (eg physical space available) mean that the process requires re-evaluation to streamline patient flow. This would reduce waiting times within the clinic, which are additional to the excessive wait times in emergency departments that are on the rise nationally (The King's Fund, 2024). Reducing waiting times would allow the clinic to review a larger number of patients and therefore ease pressure in the emergency department.

The Royal College of Emergency Medicine (2022) dictates that for some illnesses, a patient must be reviewed by a senior doctor. However, with others, management is criteria-led and dictated by aids such as clinical prediction tools, blood tests and imaging to confirm a diagnosis (Crouch and Brown, 2018). One such diagnosis is lower-limb deep vein thrombosis (DVT). Currently, work-based credentialing portfolios produced by the Royal College of Emergency Medicine and Society for Acute Medicine aim to develop practitioners to autonomously review conditions such as DVT, which is consistent with NHS strategies to improve management and reduce harm (NHS, 2017).

Evidence suggests that the management of DVT is both erratic and non-standardised across NHS trusts within the UK, despite the availability of national guidelines (NICE, 2023). Khanbhai et al (2015) noted such an issue in the north west of England, highlighting that across trusts, the professional who routinely assessed DVTs varied—36.4% advanced practitioners vs 45.5% doctors vs 18.2% a combination review. Furthermore, DVT guidelines were only available in four of the 15 trusts reviewed.

The management of DVTs by non-medical professionals has been a common practice for a number of years in alternative NHS trusts. Davis (2005) reported on nurse-led DVT clinics in the Wirral Peninsula, where nurse practitioners reviewed and ordered diagnostics for 1600 patients per annum, resulting in a positive reduction in waiting times and admissions.

A case study involving an ACP-led DVT clinic within a ‘same day emergency care’ setting at Kingston Hospital highlighted numerous positive results including reduced admissions and a streamlined pathway, with many patients quoting an excellent experience (Dunkerley, 2014). Dunkerley (2014) also noted the positive impact of autonomous practice on the ACP's job satisfaction.

ACP-led DVT clinics in the north of England have underscored several benefits of this service. Managing 115 patients annually, they avoided hospital admissions equivalent to 575 bed days and provided a financial saving of £115 000 (Neville and Swift, 2012). Evidence suggests that using criteria-led proformas reduces the overall waiting times and acts as an empowerment tool for ACPs in their practice (NHS England, 2021).

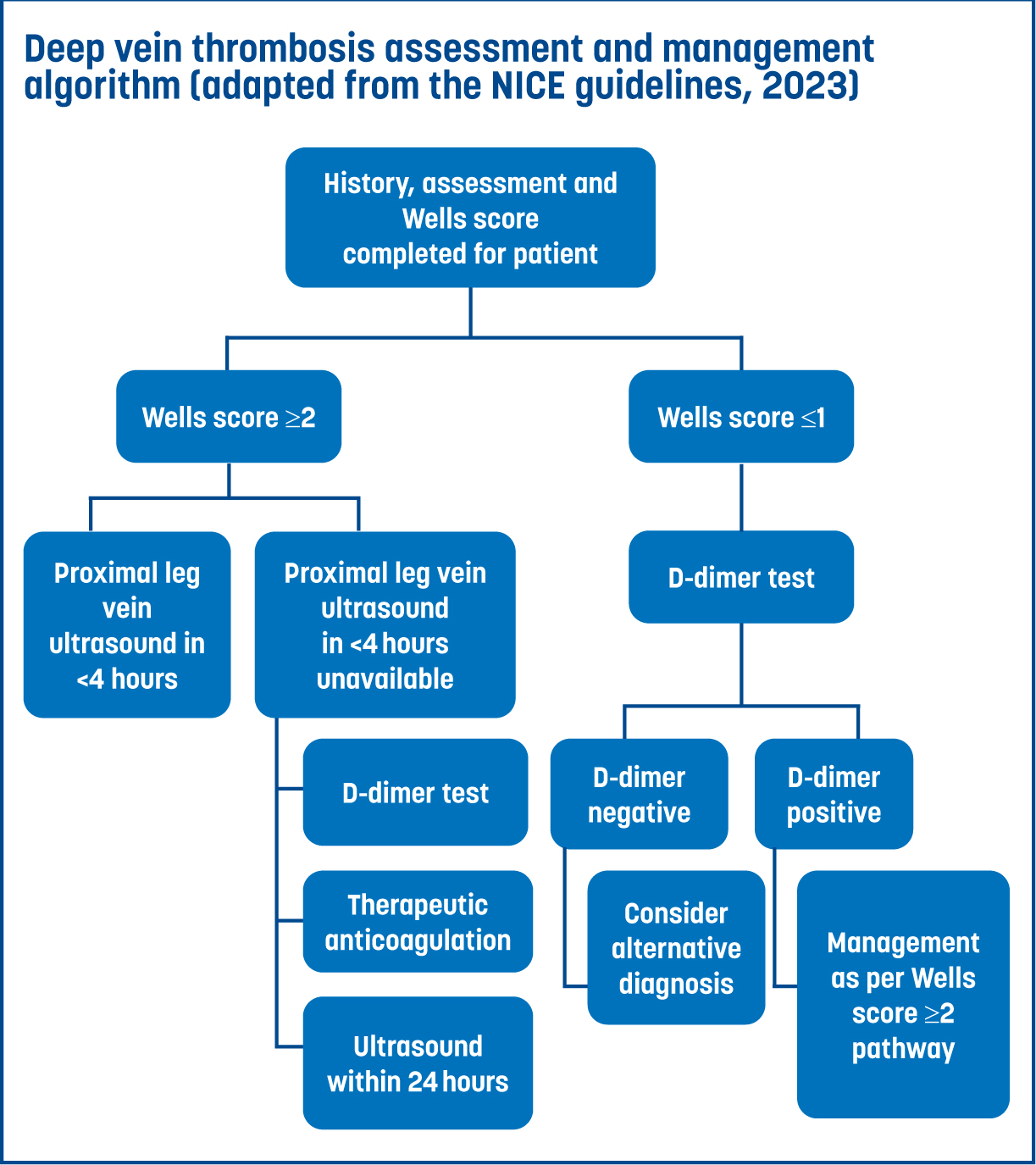

The assessment of lower-limb DVT relies heavily on criteria-driven scoring systems, with national recommendations supporting the use of a two-level Wells DVT score (NICE, 2023). The clinical prediction tool is also recommended internationally by the European Society of Cardiology in risk stratification for those presenting with suspected lower-limb DVT (Mazzolai et al, 2022).

Evidence suggests a strong negative predictive value in ruling out DVT. Modi et al (2016) noted that in a cohort of trauma patients attending the emergency department with a low probability of DVT (Wells score<1), the scoring tool was able to rule out DVT presence at a sensitivity rate of 100%. This is of particular significance in medical same day emergency care and emergency department settings where such risk stratification can help rationalise the need for further investigations. It could potentially allow for discharge of patients presenting with a Wells score of <1 and therefore a low probability of DVT. However, it is important to note that as the probability of DVT increases with the Wells score (1–2 indicates moderate risk; >2 indicates high risk), its sensitivity decreases to 67%. Despite the Wells score specificity of 90% in moderate-to high-risk patients, ultrasound imaging is needed to confirm a DVT diagnosis.

The Wells score was first developed by Dr Philip Wells in the late 1990s and is not without its limitations—it does not assign scoring to significant patient risk factors such as a family history of thromboembolism or hereditary clotting disorders like Factor V Leiden deficiency (British Medical Journal, 2022). Nevertheless, Condliffe (2016) reported implementation of a DVT pathway in a hospital in the UK, noting a positive impact on patient satisfaction in addition to reduced healthcare-associated costs. Condliffe (2016) also commented on the benefits from a clinician's point of view as the pathway ‘provides clarity in an area with a large choice of diagnostic tools [and] an increasing number of treatment options’, thereby highlighting its important role in routine clinical practice in the management of DVT.

Clinicians have been able to successfully manage possible DVT patients in a safe and efficient manner within an NHS trust (Kingston NHS Foundation Trust, 2020). Having such a pathway readily accessible for ACPs is also significant. Evidence within emergency departments suggests that ‘locating and consulting guidelines to score patients accurately was time-consuming’ (Daum, 2013). One NHS trust implemented a DVT treatment proforma and compared Wells score and ultrasound results, requesting compliance both before and after proforma implementation. Their results highlighted significant improvements in the documentation of Wells scores (9% pre-proforma vs 46% post-proforma) as well as a reduction in incomplete investigations of suspected DVTs from 45% to 12% (Daum, 2013).

Aims

This audit aims to evaluate whether ACPs in the AEC clinic can independently assess and manage patients with suspected lower-limb DVT in an autonomous manner consistent with national guidelines. ACP clerking will be evaluated against national standards for the management and treatment of DVT set by national guidance (NICE, 2023).

Audit standards

Standards 2a–2c applied only to those patients where an ultrasound scan appointment was unavailable within 4 hours of initial assessment.

Methods

Audit design

Clinical audit was selected as the method because it allowed for an objective, comprehensive review of the service (Healthcare Quality Improvement Partnership, 2020). It provided tailored data specific to the AEC clinic, leading to valid and reliable conclusions. This audit aimed to serve as the first step in a plan-do-study-act (PDSA) cycle (Blagburn, 2022) and to identify ways to optimise the AEC care pathway.

Although the initial focus was on DVT management, it could eventually serve as a foundation for expanding to other criteria-driven diagnoses that ACPs can manage independently. The audit standards and questions were developed based on national guidelines for the assessment and management of deep vein thrombosis (NICE, 2021; 2023).

Data collection

A retrospective review was conducted on 12 months of patient attendances to the AEC clinic with a confirmed DVT diagnosis at a single NHS site, covering the period from 2021 to 2022. The review included both qualified ACPs with over five years of experience and trainee ACPs currently enrolled in MSc Advanced Clinical Practice programmes.

Data analysis

The time of initial clerking and consultant physician review was recorded, and the difference was calculated in hours and minutes. To simplify analysis and determine whether the audit standard was met, a ‘Yes’ or ‘No’ was assigned to each patient for each standard.

Ethical approval

The study, as a service improvement project, was not classified as research. The NHS Health Research Authority (2022a; 2022b) confirmed that the project did not require approval from the Research Ethics Committee. The audit was registered with the trust, and all data were managed confidentially in accordance with local policies and the national general data protection regulations.

Results

Patient record analysis

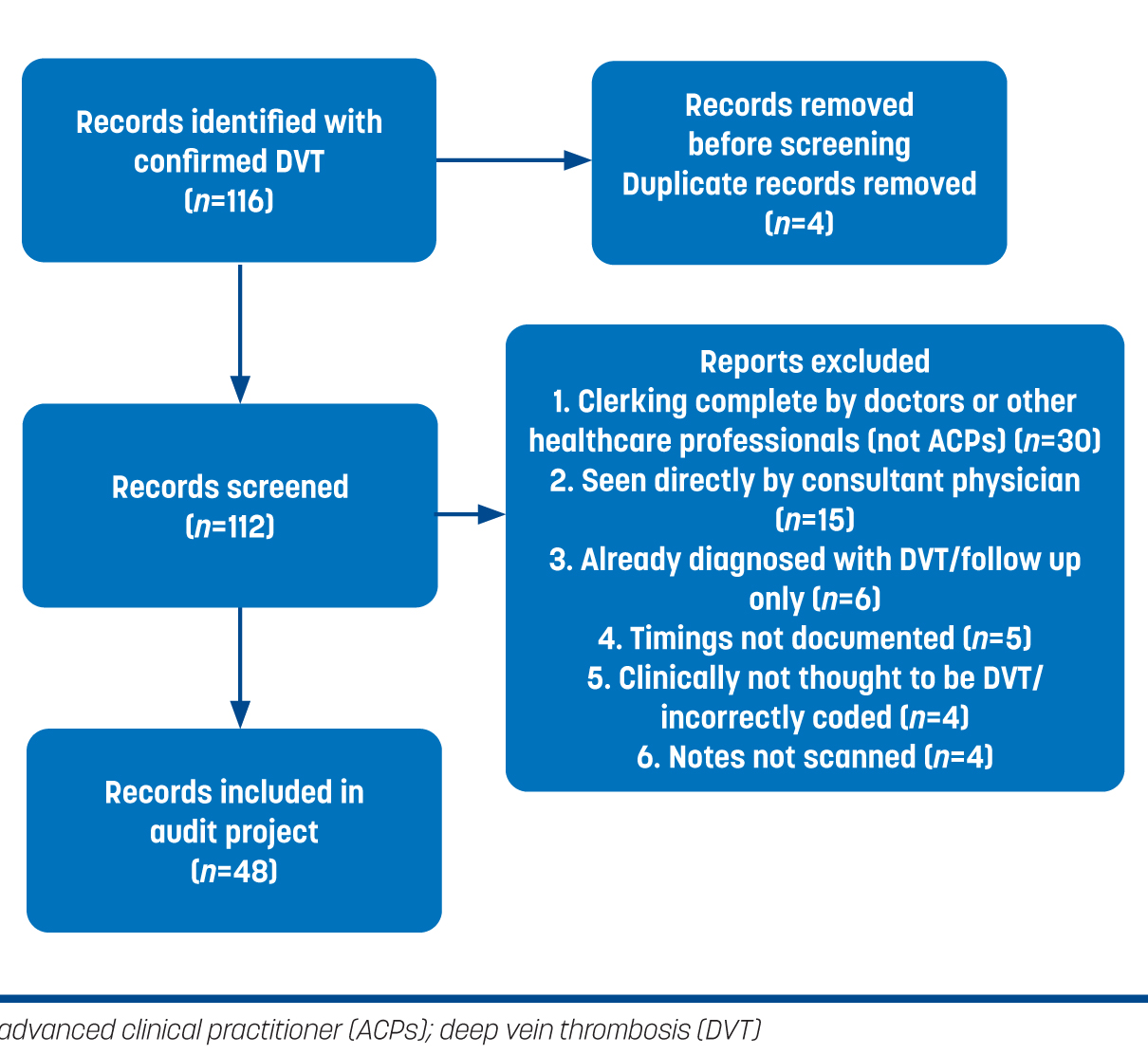

Over a 12-month period, 116 patients attended AEC and were discharged with confirmed DVT. Records were screened and 64 were excluded (Figure 1). A total of 48 patients were included in the audit.

Time-frame of ultrasound scan

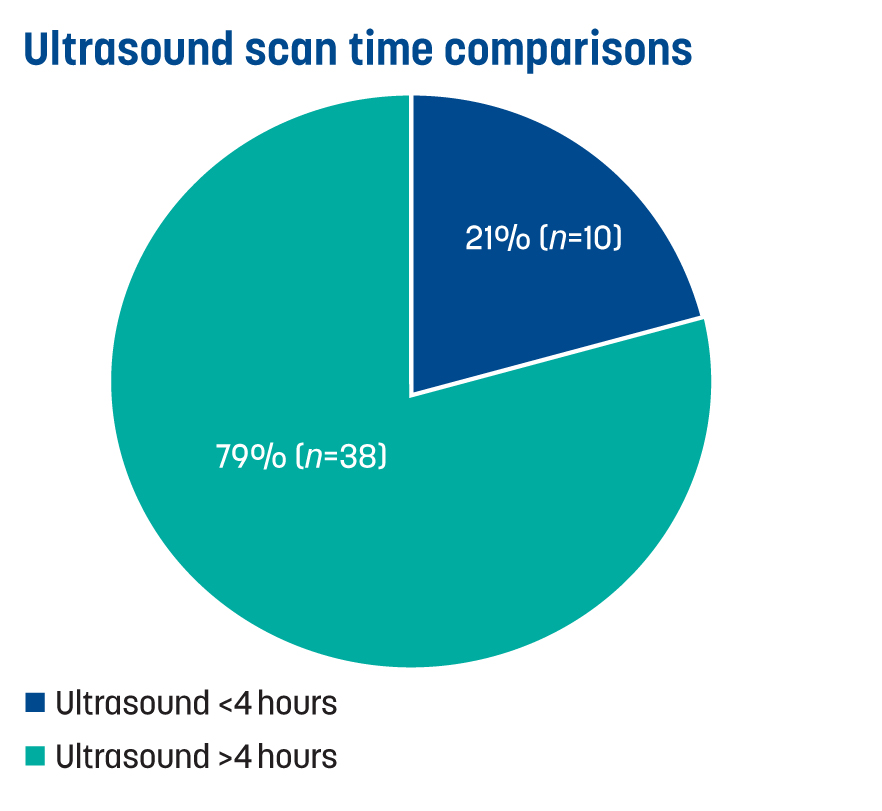

A total of 21% (n=10) received their ultrasound scan within 4 hours, while 79% (n=38) had scans outside this 4-hour window, often the following day, which required re-attendance (Figure 2).

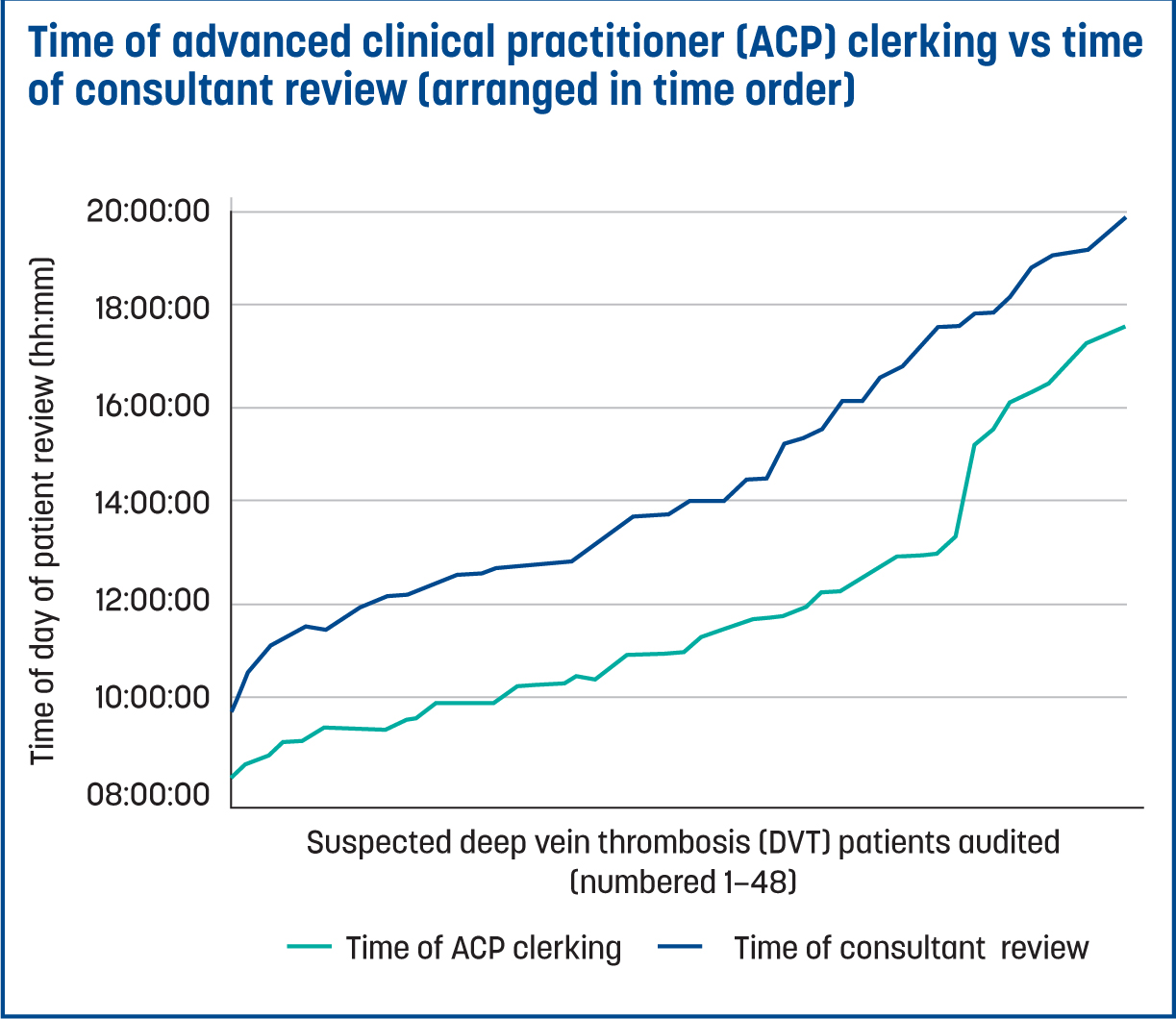

Waiting time

The 48 patients spent a total of 125 hours and 32 minutes waiting between the ACP and consultant review. Figure 3 illustrates the waiting time between ACP clerking and consultant review, with each patient waiting an average of 2 hours and 37 minutes for a consultant review.

Wells scores (audit standard 1)

There was 56% (n=27) compliance with Wells score documentation during ACP clerking. There may have been some cases where Wells scores were calculated but not documented. Any absence of documentation was considered a ‘No’ in terms of compliance.

D-dimers (audit standard 2a)

A total of 38 patients were eligible for standard 2a. Of these, 97% (n=37) had a D-dimer result. Additionally, 70% (n=7) of patients who underwent an ultrasound within 4 hours still had a D-dimer test.

Prescribing anticoagulation (audit standard 2b)

In 100% of cases where anticoagulation was required, the doses set by prescribing ACPs were in line with recommendations for weight and renal function. The most commonly prescribed anticoagulants were apixaban and enoxaparin, both of which are local first-line medications.

Ultrasounds (audit standard 2c)

Ultrasound scans were successfully requested (with the results available within 24 hours) in 100% of the audited patients.

Baseline blood tests (audit standard 3)

Among patients who required baseline blood tests, 98% (n=37) had the tests requested, obtained and results available. There was one instance where this was not fulfilled for a patient who did not have liver function tests. However, the patient had received liver function tests within the last three months.

Discussion

Waiting times

On average, patients had to wait 2 hours 37 minutes for a consultant review, having already been by clerked by an ACP. It is common for patients to wait for extended periods in the emergency department before being reviewed and transferred to AEC for further investigation. With current average waiting times in emergency departments at record highs (Banfield, 2023), any additional periods can reduce patient satisfaction and increase stress levels which has been reflected in feedback from the trusts patient and family survey.

The 48 audited patients waited a total of 125 hours 32 minutes between ACP and consultant review. A reduction in this waiting time would inevitably lead to an improvement in clinic efficiency and result in financial savings for the NHS (Baileff, 2015). No comparison was made between weekday vs weekend attendance; weekend rotas often experience lower staffing numbers and therefore, potentially longer waiting times. Similarly, there was no comparison thcare Ltd between the wait times for patients clerked by ACPs and those clerked by medical staff (doctors or physician associates). The clinicians followed the same method of wait for a consultant review following initial clerking. A number of patients (n=15) were reviewed by a consultant independently before the ACP review. This ‘single-clerk’ is not common practice and occurs during periods where the clinic is experiencing large patient numbers, which is why these were excluded from the audit.

Blood test requesting and Wells score compliance

Triage nurses often request and prepare preliminary blood tests for clerking. For patients with suspected DVT, it is common to request a D-dimer test in line with NICE (2023) guidelines. While these nurses are experienced, they are not ACPs, and there is currently no established standard for such requests within the clinic. This practice differs depending on the nurse; while this may not negatively impact patient safety it does have the potential to increase the amount of inappropriate requests for D-dimers. Further research is required in this area, including methods to resolve this issue such as a specific condition pathway which advocates for certain blood tests to be requested by all clinicians.

The documentation of Wells scoring was the poorest outcome in the audit with 56% (n=27) compliance. This may be explained by available D-dimer results influencing clinicians' decision making. If a D-dimer level was already included in the patient's biochemistry results, it may have been used to guide management decisions rather than relying on the Wells criteria, which should be used to direct initial investigations.

There is also a possibility of omissions within the clinical notes where Wells scores may have been calculated but not documented. With strong evidence supporting the use of the clinical prediction tool, such an omission can have negative consequences by way of extending patients' length of stay and the overuse of resources. One method of improving Wells score documentation is to make it a fundamental component of the pre-printed proforma (using an adaptation of Figure 4), where treatment is influenced by the score itself.

Anticoagulation prescribing

There was 100% compliance in the safety of prescribing anticoagulation (based on weight and renal parameters). However, a limitation is that there was no review of each participant's past medical history. National guidance recommends the use of apixaban or rivaroxaban for patients with proximal DVT (NICE, 2023). Local guidance aligns with this, specifically recommending apixaban as the formulary first-line agent. However, low molecular weight heparins (eg enoxaparin) may be indicated for certain patient populations, such as those with malignancy. While a direct oral anticoagulant may be prescribed for this group, certain patient-specific factors, such as tumour site and interactions with anti-cancer therapies, must be considered as outlined in the national guidance (NICE, 2023). For this reason, local guidance is to commence enoxaparin with referral to the appropriate specialty for further anticoagulation management or replacement.

For sub-populations at the extremes of bodyweight, specifically those under 50 kg or over 120 kg, national guidance recommends regular monitoring of therapeutic levels in confirmed venous thromboembolism cases (NICE, 2023). Obesity in itself represents a higher risk factor for recurrence and so, in the context of enoxaparin, 1 mg/kg twice daily is preferable dosage as compared to the conventional 1.5 mg/kg once daily dosage (British National Formulary, 2023). A limitation of the audit is that patient notes were not reviewed to determine whether those in the extreme bodyweight category had an appropriate referral for therapeutic level testing.

Furthermore, when the dosage was reviewed, the focus was solely on ensuring a safe prescription based on bodyweight and renal function, rather than considering whether a higher-risk dosage was indicated or not. Given that anticoagulation is a high risk medication and has the potential to cause harm, ACPs who prescribe it counsel patients on its usage and potential side effects. This includes a shared decision making approach where the patient is satisfied with the prescribed medication. While this did not feature as an auditable standard within this project, it is common practice within the AEC clinic for clinicians to undertake this role.

The impact of COVID-19

The impact of the pandemic is not considered to have skewed results or reduced validity. The clinic continued to run throughout the pandemic without a reduction in attendances. Local analysis of attendance data highlighted that the number of visits to the clinic during the period of 2021–2022, when the audit took place, were similar to pre-pandemic levels.

Pre-printed proforma

A pre-printed proforma for suspected DVT management assists the clinician with decision making in a time-efficient manner (Condliffe, 2016). Such proformas also help align practice with national standards, such as those audited within this project (Daum, 2013). Following the findings of this audit, AEC should aim to incorporate a proforma-based clerking for suspected DVT to streamline the process of review, avoid the need for consultant re-review, improve time efficiencies and financial savings, and maintain patient safety; adhering to national best practice guidelines (Kingston NHS Foundation Trust, 2020; Kabrhel et al, 2021). Ultimately, this will benefit patients and empower ACP staff in their ‘final decision maker’ role (Dunkerley, 2014).

Interventions regarding ultrasound

A total of 79% of patients requiring an ultrasound received one after the NICE 4-hour target. One method to alleviate the problem is through point-of-care ultrasound (having an ultrasound scanner and trained practitioner within the clinic). Evidence from systematic reviews and meta analyses identify the imaging modality to have a sensitivity of 90.1% and 98.5% specificity (Bhatt et al, 2020). This is echoed in previous research where sensitivity was confirmed to be >90% at 94.2% (Goodacre et al, 2005).

Case studies suggest that ‘one-stop’ services reduce waiting times for patients and decrease pressure on radiology (Keeling, 2012), leading to improved patient satisfaction and reducing costs (All-Party Parliamentary Thrombosis Group, 2015). The ability of ACPs to request ultrasounds would likely have influenced the results of this audit. Locally, ACPs have only recently been granted permission to request radiological imaging. This training was made available to ACPs only recently, and before this, requests had to be made by a physician, which often led to delays.

Recommendations

Limitations

Although there are cost-saving implications of the recommendations, further research specific to the local clinic is required. No comparison was made between weekday vs weekend working, where staffing levels can be variable. The audit did not look at ‘who’ requested baseline blood tests for patients, rather ‘were’ any tests requested. Triage nurses routinely requested baseline blood tests for patients themselves, which may have included D-dimers.

Anticoagulation choice is based on multiple patient-specific factors including past medical history and patient parameters. These include, but are not limited to, malignancy, hereditary thrombotic disease and extreme bodyweight. Patient notes were not reviewed to ensure such factors were accounted for, or whether appropriate referrals were made in this group. The audit did not explore the consultant viewpoint on independent management of patients by ACPs, an important consideration if pathways are developed giving more autonomy to ACPs. Patients' perspectives on their suspected DVT management or their comfort with the ACPs independently overseeing their care were not assessed. The audit also did not include ‘single-clerked’ patients who were reviewed directly by a consultant physician and therefore did not experience a wait time.

Conclusions

This audit assessed whether ACPs in the AEC clinic are adhering to national guidelines in managing suspected DVT patients. The goal was to determine if ACPs can manage these cases autonomously, without requiring a secondary review by an acute medicine physician.

Findings show that ACPs met four out of five audit standards with >95% compliance. However, Wells score documentation in clerking was only 56%, which could impact diagnosis and management. The audit also highlights potential time savings by promoting autonomous ACP practice.

Further local research is needed to quantify the financial benefits of this approach. Additionally, this audit establishes a benchmark for optimising ACP-led DVT management while ensuring patient safety. Recommendations based on current evidence and UK practice include developing a suspected DVT pre-printed proforma and condition-specific treatment pathway to support decision-making, and providing additional training for ACPs with a specialist interest in radiology to enable point-of-care ultrasound within the AEC clinic.