The four pillars of advanced practice in England—leadership, research, education and clinical practice—are the cornerstones which underpin all clinical practice (Health Education England (HEE), 2017). The devolved nature of the UK means that while England, Scotland and Wales have variations in their definitions of advanced practice (NHS Education for Scotland, 2008; Health Education and Improvement Wales (HEIW); 2023), they all share common elements based on Manley's (1997) conceptual framework for advanced practice.

Despite the emerging evidence base in support of advanced clinical practitioners (ACP) and its correlation with patient satisfaction and safety, there is variability in roles across the UK (Evans et al, 2021; Dean, 2023). Current attempts to standardise and accredit practice prove there is still a long way to go. While individual nations in the UK are developing frameworks, they are not yet able to achieve the shared goal to unite and produce joint quality assurance standards (Hill, 2024). This poses a challenge in terms of the perception of the role by patients, healthcare staff and ACPs themselves regarding what their role should entail and the development of their own professional identity (Timmons et al, 2023). This article reports on the perceptions of 29 trainee advanced clinical practitioners (tACPs), and what they view as the most and least important pillars of advanced practice, the rationale for this and what qualities they believe ACPs should possess.

Background

The ACP role can be intense and highly pressurised in its quest to satisfy medical workforce shortages (Klein et al, 2020). As the role becomes increasingly established as a credible part of UK healthcare, it brings additional challenges for both ACPs and organisations to ensure it reaches its full potential. ACP roles in the UK are multi-professional and function at a defined level of practice which supports autonomous and complex decision making (NHS Education for Scotland, 2008; HEE, 2017; HEIW, 2023) and encompasses professions such as nursing, pharmacy, allied health professionals and paramedics.

Previous literature notes that the importance of the clinical pillar often takes precedence, to the detriment of the other three pillars (Henderson, 2021; Fielding et al, 2022; Mellors, 2023). Prioritising the development of all four pillars for ACPs within the NHS England (2023) Long Term Workforce Plan is integral to strengthening ACP roles (Gloster and Leigh, 2021). Conway and Barratt (2023) recognised a new era of multi-professional care, emphasising that interprofessional and collaborative working enriches teams by incorporating diverse professional backgrounds, ultimately contributing to positive patient outcomes.

Becoming an ACP requires a Master's degree from a designated training and education programme, typically in the form of an MSc Advanced Clinical Practice degree. To achieve professional competence in line with the HEE multi-professional framework for practice, the requirements for Master's level study aim to standardise and safeguard care (HEE, 2017; Gloster and Leigh, 2021). The competence required to practice safely and the potential for litigation at advanced practice level is indicative of the high level of risk and autonomous decision making required for the role. The Nursing and Midwifery Council (NMC) (2024) proposal to regulate advanced practice recognises the complex, autonomous and high-risk decision-making roles that nurses and midwives carry out. They aim to develop standards of proficiency for advanced practice and regulate such roles that have the potential to make a significant difference in safeguarding the public, organisations and clinicians (Palmer et al, 2023). This could encourage similar developments from the Health and Care Professions council, which registers, quality assures and governs the multi-professional regulation of other healthcare and psychology professionals practising as ACPs in the UK. The vision for ACPs is to ensure competence, confidence and credibility in understanding and engaging with all four pillars of advancing practice. However, ACPs are primarily expected to deliver effective bedside clinical care at an advanced level, which raises a challenge for front-line practitioners trying to develop in a role that lacks standardisation on a national level (Mann et al, 2023). Qualified ACPs should be well-rounded practitioners, practising across all pillars of advanced practice. Trainee ACPs learning from them should recognise and understand the importance of this balance, especially during the early stages of their training. It would be remiss not to acknowledge the inequality across the pillars, particularly when evidence suggests a lack of clinical research undertaken and led by ACPs (Dean, 2023). This is further supported by the recognition that non-medical healthcare research has not advanced at the same pace as other disciplines within the UK higher education sector. In recent rounds, the research excellence framework and UK National Institute for Health Research Fellowships have shown significantly lower representation compared to medicine (60–80%) (National Institute for Health Research (NIHR), 2021; Smith et al, 2024).

Gaining insight into trainees' perceptions of the ACP role is essential. It offers an opportunity to refine educational programmes, enhance curricula and support practice learning. This will help to ensure that all four pillars are embedded throughout tACPs' educational pathways and are sustained beyond qualification.

Aims

This research aims to identify tACPs' perceptions of the four pillars of advanced practice. The most and least important pillars of advanced practice, along with the qualities an ACP should possess are also explored in the research to understand participants' perspectives.

Methods

Ethical approval

Ethical approval was obtained through the university where the study took place (approval reference no: 23/NAH/008). In compliance with the relevant professional research guidelines and ethical principles, professionalism was maintained and participants were treated with fairness, dignity and sensitivity. All participants were aware that they could withdraw at any time from the research and that this would not affect their studies or student experience in any way.

Participants

The study was conducted in a UK Higher Education Institution (HEI) which provided programmes of study for tACPs. Purposive sampling strategy was used as it was reflective of the larger population (Gray, 2014). These sampling strategies have been used in many studies related to nursing and nurse education (Morrell-Scott, 2022). The potential study population was n=217.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

All participants were full-time tACP students on either an apprenticeship or a non-apprenticeship programme. Any students who were not tACPs were excluded. All eligible participants were emailed information about the research, including a participant information sheet and a link to the online questionnaire.

A total of 29 students self-selected to be a part of the research. The participants who completed the questionnaire (n=29) belonged to a range of professions: nurses (n=19), paramedics (n=6), pharmacists (n=1) and physiotherapists (n=1). Two students did not complete this part of the demographic details. None of the sample group withdrew from the study after agreeing to participate.

Data collection

Content validity was ensured to appraise the questionnaire and ensure that the questions were suitable and met the aims of the research (Taherdoost, 2016). A draft questionnaire was developed and shared with an external team of five to ensure relevancy and credibility of the questionnaire.

The external team included three practising ACPs, one ACP senior lecturer and a recent ACP graduate. The researchers believed this process added credibility and validity to the research. Based on feedback, minor modifications were made and the questionnaire was distributed.

This research employed a mixed-methods approach featuring a questionnaire grounded by the positivist paradigm (Macarthur and Clarkson, 2023). Data were collected through an online questionnaire to allow participants to undertake this at their leisure, within a designated time frame, making it convenient for them.

The questionnaire included six closed questions to gather demographic information about each participant's programme (eg apprenticeship or standard programme), professional body, time qualified before starting the programme, gender, employment band before study and length of time on the programme. Three free text questions asked were:

Data analysis

Quantitative data were analysed using descriptive statistics. The free text qualitative questions were interpreted using thematic analysis. In line with the principles of thematic analysis, themes were developed after identifying patterns within the data (Braun and Clark, 2006). The researchers also worked independently to analyse the data and to discuss and develop the themes. This ensured that the process was authentic and consistent with the principles of thematic analysis.

Results

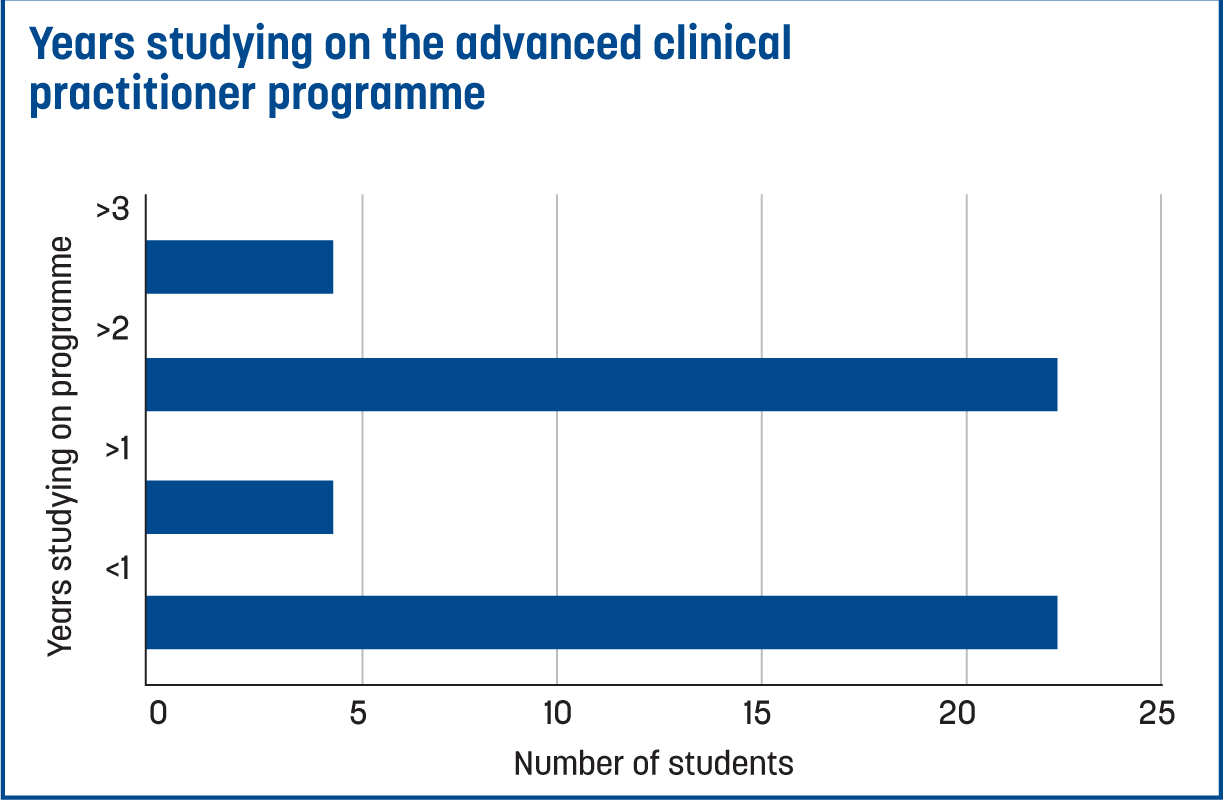

There were 22 female and 7 male participants. Details of the participants' demographics are discussed in Table 1, Table 2 and Figure 1. The results of the questions are discussed individually to offer a clear insight into the responses.

| Years registered before taking on the tACP role | No of participants |

|---|---|

| <5 | 1 |

| 5–10 | 10 |

| 10+ | 6 |

| 15+ | 12 |

trainee advanced clinical practitioner (tACP)

| Agenda for change band | No of participants |

|---|---|

| Band 5 | 2 |

| Band 6 | 8 |

| Band 7 | 15 |

| Band 8a or equivalent | 4 |

| Band 8b or equivalent | 0 |

| Band 8c or equivalent | 0 |

What did participants perceive was the most important pillar?

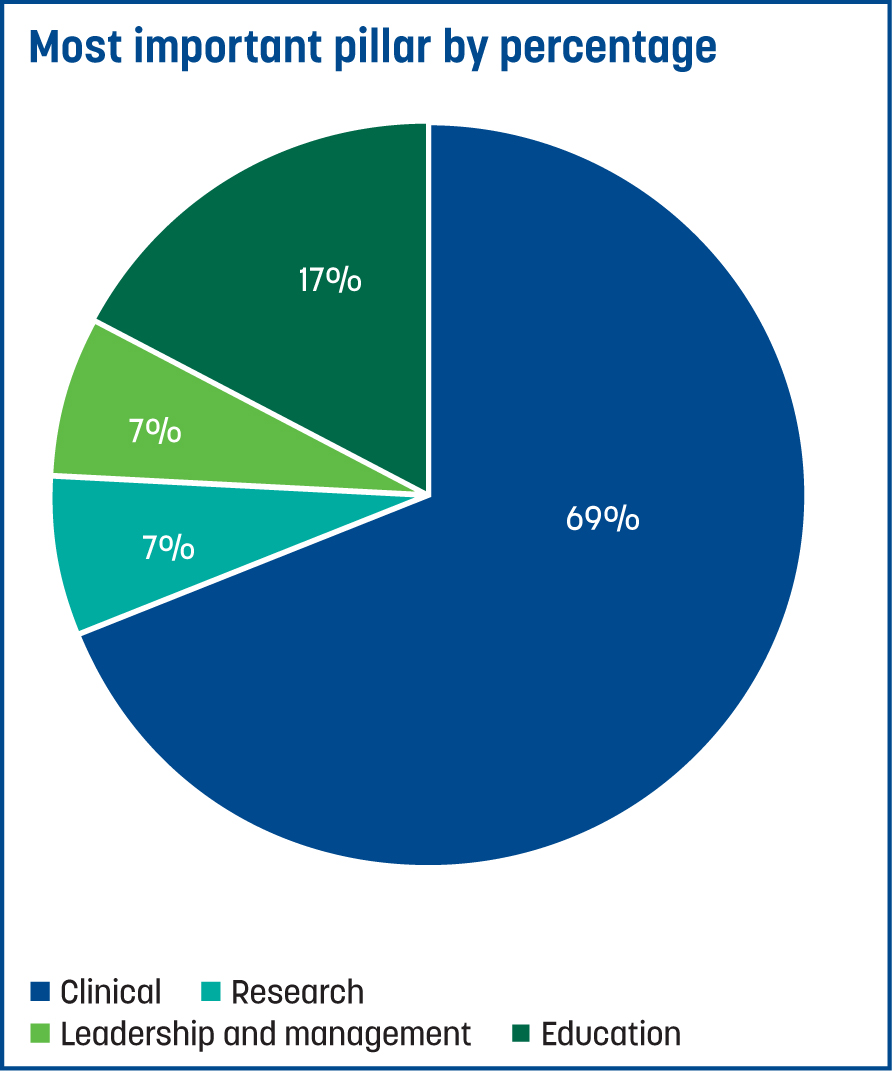

Overall, the most important pillar according to tACPs is the clinical pillar, with education as the second most important (Figure 2). There were various reasons for this perception explained under the following themes.

Survival to prove oneself

The clinical pillar was regarded as the most important by the majority of participants. They felt that their peers judged them based on clinical competence and that they needed to ‘survive’ in the role by avoiding errors.

‘This is the area I am going to be expected to prove myself in.’

It is all about the patient

Others believed that competence in clinical skills should be the priority, as it is directly linked to patient care. Participants expressed a strong dedication to their patients, with their commitment to providing quality care being the key reason the clinical pillar was viewed as the most important.

‘My role as a paramedic is mostly patient facing, so I believe having advanced clinical knowledge is important.’

‘It doesn't matter how much education or research or audits you do; if you can't do the hands-on work what's the point.’

‘I am a clinician and want to ensure my clinical skills are the best they can be.’

Preparation for the future

Many participants felt that the clinical pillar underpins the other three pillars, which is why they considered it the most important. Additionally, participants felt that clinical skills should be practised first and research, leadership and education would develop with time.

‘I will need more experience working within different settings at an advanced level before I return to teaching.’

‘With clinical ‘mastery’ I will be more confident in practitioner leadership, able to identify education needs and act as practitioner role model; enact research-based on clinical needs.’

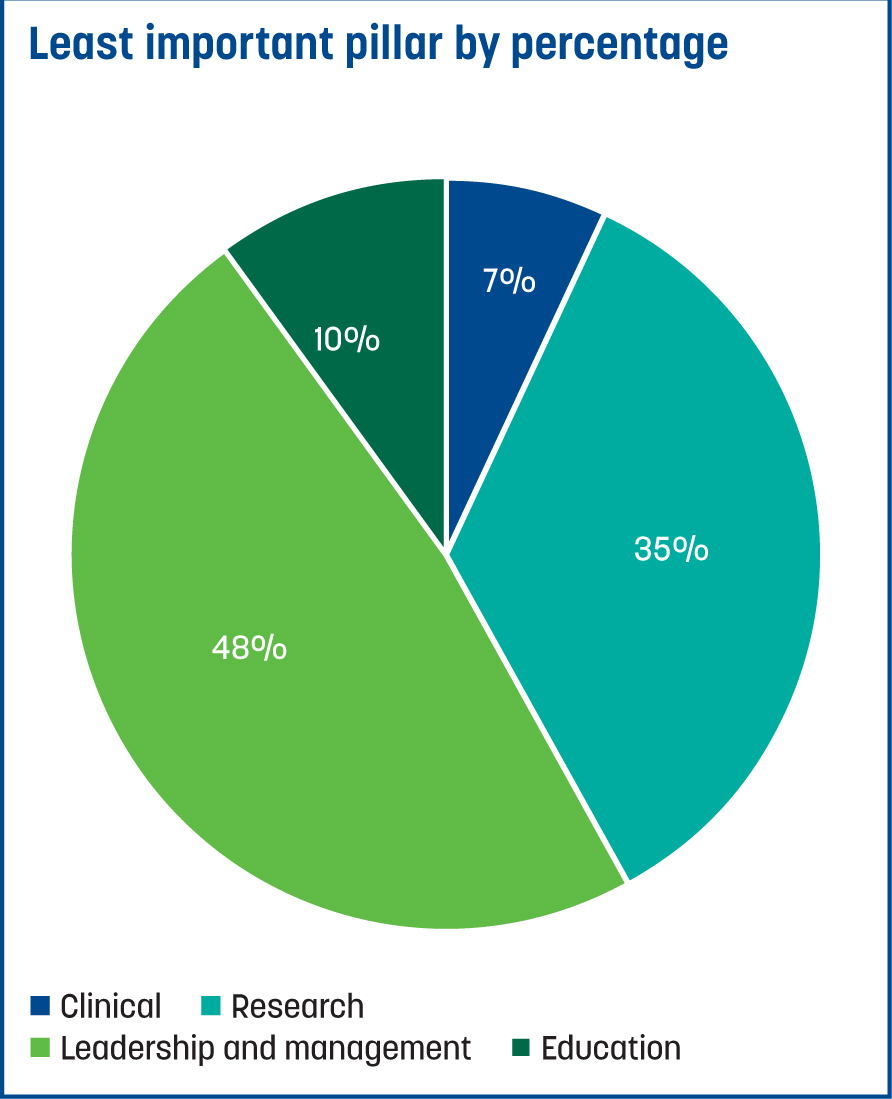

What did participants perceive as the least important pillar?

The least important pillar, according to the participants, was leadership, followed by research as the second-least important (Figure 3). There were varying accounts for this opinion, examined in the following themes.

No time for research

Participants who chose research as being the least important largely cited time as the main reason. Participants expressed that given their day-to-day clinical demands they would not have time for research; they did not consider research being unimportant.

‘I am also conscious that once having completed the course my availability to continue with research will be more constrained, because of expectations and time limitations.’

‘The organisation only expects clinical.’

Participants felt that leadership skills would not be expected of them by their organisation. For some, not wanting to line manage was another reason.

‘I do not believe my organisation will give me any leadership function on completion.’

‘If you want to do management then you shouldn't be an ACP.’

ACP qualities

Participants' responses focussed around doing their best for their patients, providing excellent care and maintaining safety (Table 3).

| Synonym group | Words |

|---|---|

| Autonomous | Adaptive, progressive, constantly learning, pushes themselves, proactive, dynamic, flexible, independent |

| Caring | Supportive, compassionate, empathetic, dedicated, reassuring |

| Reflective | Good reflector, humble |

| Learning | Constantly learning, keen to gain skills, enthusiastic, innovative |

| Experienced | Highly experienced, highly skilled, well-rounded knowledge, broad knowledge |

| Leadership | Leader, role model, excellent leadership skills |

| Competence | Highly competent, expert, confident, highly specialist and skilled, competent practitioner |

| Communication | Good communicators, expert communicator, excellent communicator, collaborative communication skills |

| Skill | Clinical expertise, clinically skilled, highly skilled, enhanced skills and knowledge, clinical skills, professional skills, clinical examination, therapeutics, competency in clinical skills, treatment and diagnostics |

| Holistic | Holistic, whole person-centred, comprehensive assessment and treatment, holistic approach |

| Confidence | Confidence within their specific skill set, confident, determined, confidence, reassuring |

| Education | Knowledge, education, academic skill, excellent knowledge in areas of clinical and educational |

| Initiative | Proactive, dynamic, innovative |

| Accountability | Responsible, adheres to the Nursing and Midwifery Council code |

| Advocacy | Advocates for patients and senior clinical staff, supports patient safety and hospital avoidance |

| Decision making | Clinical reasoning and decision making skills |

| Approachability | Approachable, open to help, good leadership skills |

| Empathy | Empathetic, compassionate, understanding |

| Resilience | Resilient, persistence, determination |

Discussion

It could be reasoned that the study findings correlate with pre-existing research, which suggests that while the clinical pillar is well established, the remaining pillars of advanced practice require further development and focus (Henderson, 2021; Fielding et al, 2022; Mellors, 2023). The study provides a strong indication that students who are already in tACP positions have preconceived views about the importance of each pillar and its implementation as part of their current role. Participants can also identify aspects of the role that may not be fully met when transitioning into their qualified positions. For example, they may anticipate limited time for research (Fothergill et al, 2022; Mellors, 2023) because of organisational expectations. The multi-professional framework for advanced practice (HEE, 2017) identifies the role of the ACP as being much more than a clinical practitioner.

It would be neglectful to ignore the significant demands on ACPs from organisations with complex patient caseloads, who require assessment, diagnostic investigations and treatment. Therefore, the drive to address this imbalance will always be the priority (Mann et al, 2023). The three remaining pillars still require nurturing and it is up to the trainees and their supervisors to demonstrate how they will meet all four. A further challenge which may lead to misunderstanding regarding the importance of the pillars is the title of the role. The fact that the title ACP has the term clinical within it may be part of the wider issue as to why individuals perceive clinical as the most important pillar. The role organically developed as a means to address medical workforce issues, so this clinical aspect has been the most recognisable element of the role (Timmons et al, 2023). The title itself could prove a barrier to developing skills within other areas, especially if understanding the role is not clear to stakeholders and organisations from the outset (Schwingrouber et al, 2024). This emphasises the importance of role accreditation by professional bodies to ensure practitioners maintain their advanced skill sets and employers understand the necessary level, scope and vision required to develop an autonomous advanced practice workforce (Hill and Mitchell, 2021).

It may be that ACPs are viewing the three pillars of research, education and leadership as separate entities. Ensuring effective supervision and education may help tACPs to understand how each pillar links to one another in functional day to day practice when delivering patient care. The HEE (2021) have provided clear standards and expectations for the supervision of the ACPs. Harding's (2020) project attempted to establish the training and development of supervisor practitioners using a multi-professional approach to improve consistency and limit variations across healthcare sectors. This advocated a blend of coordinating educational and associate supervisors with partnered specialty knowledge and skills development to guarantee supervision which has a professional focus and prioritises public safety within advanced practice. This model of supervision lends itself to enabling tACPs to understand the correlation of all pillars and supports a multi-professional perspective on how they can be achieved.

An example of this is understanding the research pillar. The participants assumption that, as qualified ACPs, they would have limited time to undertake research highlights the need to explore effective ways to integrate this element of practice. Specific protected research time may provide the solution because no practitioner would overlook patient care to undertake work seen as non-essential. It could be argued that protected time as a scheduled job plan requirement would allow ACPs to develop their research skills and practically undertake and lead research. This would authentically promote the research pillar and seek to develop ACPs as research leaders to set examples for those aspiring to the role.

Given the demands that all healthcare staff face, and that pressures are unlikely to be resolved unless time is mandated, the prospect of ACPs undertaking and leading research will remain negligible. Research is often a neglected pillar, but for an ACP to be competent, safe and practicing within their own professional scope, they must possess the knowledge and skills to identify pertinent literature, while evaluating its quality and interpreting its results for application to clinical practice (Fielding et al, 2022; Fothergill et al, 2022).

Dean (2023) echoed this sentiment and identified challenges in developing ACPs to influence the culture of research. Dean (2023) identifies clinical academic careers as a route yet acknowledges the challenges associated with integrating research and clinical practice, which often relies on self-motivation to engage in research as opposed to following a predefined pathway (Trusson et al, 2019). Therefore, there should be a balance between organisations and ACPs to implement innovation methods. Polak and Allan (2023) suggested the use of journal clubs to create a peer-learning approach to research appraisal, which promotes an active style of learning and upholds the application of research knowledge to evidence-based practice (Hew and Lo, 2018). The Royal College of Physicians (2022) echoed the NIHR position statement which held the view that research was everyone's business and the study findings have proven that this must be encouraged for ACPs. Badu (2023) called for urgent collaborations between clinical research regulatory agencies, NHS organisations and pharmaceutical companies to support the progression of ACP roles in clinical research. It further highlights that for the ACP role to progress it must be appropriately used and the cross-pillar knowledge, skills and experience for ACPs must be valued.

It could be reasoned that the ACP role has been too pioneering and evolved quickly without the infrastructure in place to fully support ACPs to meet all the elements. Despite increases in the numbers of ACPs, the NHS England (2023) Long Term Workforce Plan identified that workforce numbers have failed to keep pace with the increased demand for care, as well as the technological advances and the expectations of those receiving care. Its train, retain and reform mantra could provide an opportunity to reflect on how to embed all pillars equally into the future ACP role.

Limitations

This was a small-scale research study from a sample of students from one HEI. However, this smaller, in-depth study allowed for an insight into the students' perceptions. Despite this, the researchers are confident that given the quality processes used and that other healthcare education research (Watts and Davies, 2014) has used small numbers, this is an acceptable approach. Another limitation is that this is only the perspective of tACPs, not experienced ACPs. It may be possible that once ACPs have consolidated clinical skills, they may begin to appreciate the other pillars in equal measure.

Recommendations

A larger-scale study recruiting qualified ACPs may determine whether perceptions of the most important pillar evolve alongside role development, individual experiences and career opportunities. Trainees should spend time learning from a range of different supervisors to understand how they navigate and fulfil the four pillars effectively. The title ACP may be reconsidered in the future, if the role continues to be challenging for ACPs to fulfil in its entirety.

Conclusions

This research reported on the perceptions of tACPs and their perceptions of the most and least important pillars of advanced practice, their reasoning for this opinion and the qualities they believe ACPs should possess. It is evident that, despite the development of the ACP role, there is some disconnect among the pillars of advanced practice and the clinical pillar is perceived as taking precedence over the others in order to survive in advanced practice roles. Future consideration of job descriptions, trainee expectations, and educational and supervision strategies must support and guide tACPs in emphasising all pillars to ensure equal integration in training.