Advanced clinical practitioners (ACPs) have emerged as a key professional group within the primary care multidisciplinary team (MDT), responding to increasing demographic and health system pressures (Evans et al, 2021). The expansion of the ACP workforce, aligned with the Health Education England framework for advanced practice (AP), is a central component of the NHS workforce transformation policy (NHS Digital, 2023). As outlined in the NHS Long Term Plan, the target for the next five years is to expand the AP workforce by 46% and to enroll up to 5000 ACPs in higher education programmes annually (NHS Education, 2023). However, this emerging professional group faces a significant lack of governance oversight because of the absence of a unifying professional body, contributing to a perceived lack of professional identity among ACPs in clinical practice (Timmons et al, 2023). This ambiguity around professional identity has led to employers misunderstanding both the role of ACPs and their clinical capabilities. More specifically, there is a lack of clarity regarding the post-qualification support required by ACPs to advance their clinical practice effectively (King et al, 2017).

As a result, systemic variations in the quality of training for ACPs persist across primary care settings. This issue was well-articulated in a cross-sectional analysis by Fothergill et al (2022), which assessed educational standards for advanced practice:

‘ACP respondents reported ongoing concerns regarding the variability and quality of training across different professions and settings… Further support is required for high-quality supervision, support and training for ACPs nationally, to enhance ACP professional development and career progression.’

The Haxby Group in Yorkshire has maintained a well-established AP workforce since 2016. As the team has expanded, an increasing number of clinicians have transitioned from trainees to qualified staff members. To address the evolving CPD needs of these qualified ACPs, the organisation published an internal workforce strategy for AP in 2022. This strategy used the maturity matrix—a national tool designed to assess the organisational maturity of advanced pathways and to ensure that clinicians meet national standards of practice (NHS England, 2022a).

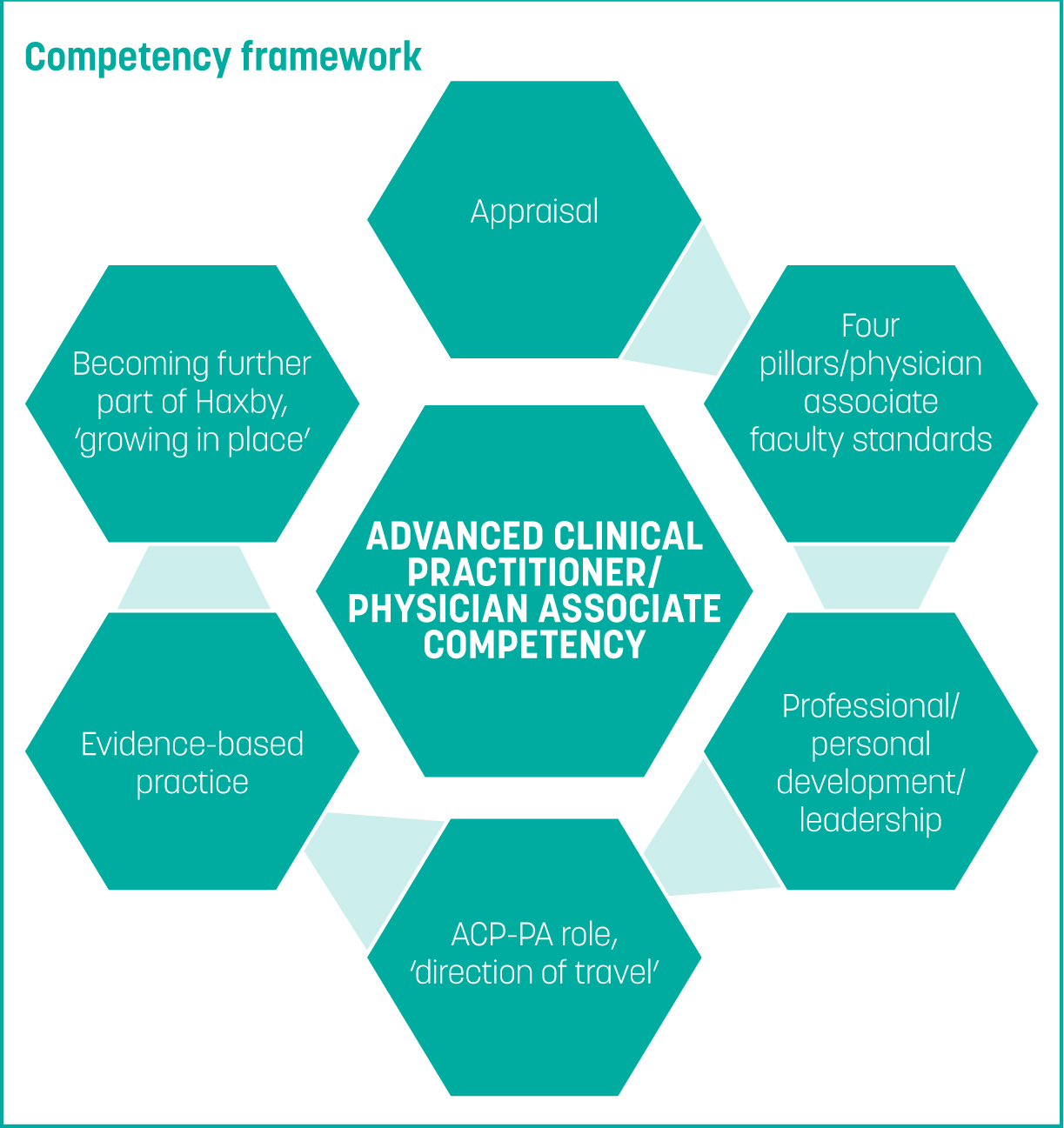

The maturity matrix assessment identified a local training gap for qualified ACPs, specifically a lack of structured CPD opportunities beyond university education, to support their continued professional growth. In response to this finding, the Haxby Group appointed an ACP teaching fellow tasked with designing and implementing an internal competency framework training programme. The primary goal of this framework was to support and enhance the clinical knowledge and skills of qualified ACPs in key areas of primary care. The training was tailored to align with each clinician's career pathway and was integrated into the appraisal process, fostering the development of specialised skills relevant to their practice area. This article explores the development of the competency framework and its establishment as a key assurance structure supporting high-quality organisational governance at the Haxby Group. The article examines how this framework could influence the broader national governance landscape and discusses how the project contributed to staff retention in North East England, a historically challenging region for recruitment. The article also highlights the wider benefits of this regional success, including its implications for the national agenda and the potential development of a primary care credential for ACPs in the UK.

Method and delivery model

The competency framework was launched internally in February 2023 (Figure 1). Following a year-long internal pilot, it was introduced regionally in March 2024. The training framework centres on the four pillars of AP: clinical, research, leadership and education. This CPD structure ensures that clinicians fully engage with the comprehensive scope of the ACP role, addressing the often-overlooked pillars of education and research alongside the more commonly emphasised clinical aspects of learning and patient care (NHS Employers, 2023). Competency framework training was delivered through 4-hour monthly teaching sessions as part of extended supervisor learning events (ELSE). Each ELSE session was tied to specific learning framework outcomes, which informed workplace-based assessments such as consultation observation tools (COTs) and clinical examination procedures (CEPs). Internal ACPs were paired with a GP mentor for 1-hour monthly meetings to review and enhance their individual personal development plans. For external ACPs, who typically already have GP mentors in their practices, the framework offered one supervision session per year. The subjects were tailored to ACP clinical needs, identified through an internal questionnaire completed by all qualified ACPs within the practice. This ensured that CPD topics addressed the priorities and gaps perceived by the practitioners themselves. All CPD achievements were documented using the FourteenFish CPD appraisal tool, a platform procured by the Haxby Group in response to the questionnaire feedback. This tool, widely recognised as a standard GP CPD appraisal system, provided ACPs with a structured and accessible way to record and reflect on their learning (Health Education England, 2023).

Results and feedback

Results and feedback were gathered through both qualitative and quantitative methods, including participant surveys conducted after the initial 3-month trial (Tables 1and2).

| Questions | Responses |

|---|---|

| Do you feel your clinical knowledge has improved since the introduction of the competency framework? | 5 answered yes; 0 answered no |

| On a scale of 1–10, to what extent do you feel your clinical knowledge has improved? | 1 scored 7/10; 3 scored 8/10; 1 scored 9/10 |

| Do you feel your clinical skills have improved since the introduction of the competency framework? | 5 answered yes; 0 answered no |

| On a scale of 1–10, to what extent do you feel your clinical skills have improved? | 2 scored 7/10; 2 scored 8/10; 1 scored 9/10 |

| Do you feel the competency framework is well-suited to your role in general practice? | 5 answered yes; 0 answered no |

| On a scale of 1–10, how well do you feel the competency framework aligns with your role in general practice? | 1 scored 7/10; 4 scored 10/10 |

| Do you feel the competency framework meets your Continuing Professional Development (CPD) needs? | 4 answered yes; 1 answered no |

| On a scale of 1–10, how well does the competency framework meet your CPD needs? | 1 scored 6/10; 1 scored 9/10; 2 scored 10/10; 1 person did not answer |

| Do you feel the competency framework serves as an effective CPD tool that can meet your long-term professional development needs as a qualified clinician? | 3 answered no; 2 answered no |

| On a scale of 1–10, to what extent do you feel the competency framework serves as an effective CPD tool to meet your long-term professional development needs as a qualified clinician? | 1 scored 3/10; 1 scored 6/10; 1 scored 9/10; 2 scored 10/10 |

| Question | Response |

|---|---|

| How useful did you find the training? | Feedback from respondents was 100%, marked 10/10 |

| Do you think there was a good balance between practical application and theory? |

Overall, the respondents gave a positive feedback, including:

|

| Was the information pitched at the correct level? |

Overall, most of the answers were yes; feedback included:

|

| Do you have any suggestions that could improve training? |

|

| Was adequate time allocated for the session? | Overall response was 100% |

| What was the impact of attending these sessions on your clinical knowledge? |

|

Advanced clinical practitioners (ACPs); general practitioner (GP)

Analysis and discussion

Clinical and organisational advantage

Five staff members participated in the initial survey. Although the sample size was small, it was reflective of the ACP cohort, as all participants were clinicians who had qualified within the last 24 months. Feedback indicated that the competency framework had positively impacted their clinical skills and knowledge. The length and frequency of the CPD sessions were well-received, with 100% of ACPs in the pilot agreeing that the allocated time was adequate. These sessions were conducted over 4–hour periods and followed a structured format, beginning with theoretical learning before progressing to practical applications. Clinical skills practice and assessment were enhanced through the inclusion of subject patients. For instance, patients with conditions such as multiple sclerosis, progressive supranuclear palsy and incomplete spinal cord injuries (C4–5) participated in a neurological CPD session to facilitate hands-on education.

Participants appreciated the balance of theory and practical learning, noting increased confidence and knowledge gained through the ELSE sessions. However, concerns were raised about how the workplace-based assessments (WBAs), such as COTs and CEPs, would integrate into the CPD model. Mentorship time for WBAs proved challenging to schedule during the 3-month pilot because of systemic pressures, including the demand surge following the January 2023 Streptococcus A crisis (Hay, 2023) and the lingering effects of the COVID-19 pandemic (British Medical Association, 2024). These factors led to longer patient waiting times, diverting focus away from mentorship activities.

The NHS Long Term Plan (NHS England, 2019) and subsequent people plan (NHS England, 2020) emphasise the need for educational transformation to support roles such as ACPs, which are still evolving. For this project, key measurable outcomes included clinician retention and staff satisfaction. Recruiting and retaining staff in socioeconomically deprived areas is particularly challenging, imposing significant financial and cultural strains on organisations. Constant recruitment cycles burden departments such as human resources and finance, while persistent staff turnover disrupts team dynamics and leads to change fatigue. Since the pilot, no qualified staff have left the practice. The framework has also positively influenced recruitment and retention of other teams, such as salaried GPs who have reported benefits from the support provided by well-trained ACPs.

In terms of softer outcomes, feedback on CPD relevance and AP succession planning revealed mixed insights. While most participants felt the competency framework met their current CPD needs, only 60% believed the existing delivery model would be suitable for their future learning requirements. Potential reasons include preferences for external CPD events, individual learning styles and career paths diverging from general practice. The lack of fully integrated mentorship time may also be a limiting factor for long-term satisfaction. This highlights the need for ongoing monitoring and refinement to ensure the framework remains aligned with ACPs’ evolving needs.

In terms of succession planning, the framework naturally fostered the development of a leadership group among qualified staff, creating a positive cultural shift. This leadership dynamic is expected to influence trainee ACPs, establishing strong local team dynamics and ensuring that CPD needs are met post-qualification. The framework also addresses the critical training gap in CPD for newly qualified ACPs, offering a structured solution.

From an organisational perspective, implementing a new training structure requires careful navigation of risks and facilitators. In healthcare, training and governance are deeply interconnected (NHS England, 2023). This is especially relevant for ACPs, as the absence of national regulation places the onus of managing clinical risk on employers (Diamond-Fox and Stone, 2021). While the maturity matrix published by the AP School (NHS England, 2022b) helps organisations assess their structural readiness for AP roles, its application varies. Primary care practices, often smaller than secondary care trusts, face unique challenges in developing robust governance structures (NHS Confederation, 2023).

At the Haxby Group, the competency framework has become a cornerstone of the internal ACP workforce strategy. This strategy ensures that governance is embedded across the AP career pathway, enabling safe clinical practice and mitigating organisational risk. The framework emphasises the four pillars of practice at all career stages. This comprehensive approach safeguards clinical risk, nurtures leadership and fosters relevant research, aligning with the unique demands of primary care. The constant reinforcement of these principles during management meetings was instrumental in the framework's development, implementation and sustainability. This focus on aligning CPD with the four pillars of practice was arguably the project's most critical driver, ensuring its long-term success and relevance.

The challenges

From an inception perspective, there was little evidence of this type of framework being developed within primary care, aside from a competency framework aimed at nurses published in 2020 (Health Education England, 2020). Reviewing the evidence nationally, there was no planned primary care credential for general practice being developed by the AP school, despite primary care having specialty status (McManus and Hobbs, 2016). Therefore, the trial was largely based on anecdotal evidence from an internal qualitative survey of ACPs, outlining what they might need from a competency framework, while structurally aligning with frameworks aimed at core specialties within secondary care, such as the Royal College of Emergency Medicine publication for emergency care (2024).

It is also important to consider the barriers and facilitators of clinical and fiscal responsibility when implementing new governance structures. Reduced clinical capacity because of missed patient appointments will always be a potential barrier when clinical staff are assigned CPD time (Mann et al, 2023). For the Haxby Group, 80% of same-day acute appointments across the practices are delivered by ACPs. When ACPs attend CPD sessions, the loss of acute appointments creates a clinical risk, which has to be backfilled by the GP team. To mitigate this, workforce data were reviewed before the pilot's inception, with Thursdays identified as the day with the least risk of disrupting clinical work.

The cost influence was pre-empted before delivering the pilot and had been approved, accounting for all relevant factors, as summarised in a proposal to the Haxby Partnership 6 months before the project's initiation. An internal red line that was never crossed was to avoid using locums to backfill ACPs attending CPD. Although difficult to calculate, the initial fiscal outlay of delivering CPD was balanced by the savings from reduced staff turnover and increased patient appointments as more ACPs became qualified. Much of the initial real cost was mitigated by the educational delivery, as the CPD programme was internally built and delivered by partners and clinicians who were heavily invested in the project and often built training programmes within their own personal or pre-agreed administration time. Therefore, the fiscal conclusion of delivering the project had some initial perceived short-term risk, with clear medium-term empirical justification and only predicted tangible longer-term financial benefits from delivering the CPD framework regionally.

Conclusions

The overarching aim of this pilot was to deliver a CPD format for qualified ACPs to support retention and recruitment in a socio-economically challenging area of the UK. Overall, the pilot has been assessed as successful. The feedback from participants has been largely positive, with a clear desire for the CPD framework to continue, although there is caution about its educational longevity, particularly regarding teaching delivery and access to other forms of CPD. Organisationally, the pilot has now been adopted as a governance mechanism to manage AP clinical risk within the practice. The project has seen a successful regional launch that will improve staffing retention and positively impact patient care in East Yorkshire. On a national level, this work highlights the need for resources to be focused on developing and implementing an AP primary care credential. Such a credential would standardise governance for ACPs within general practice, informed by the four pillars, and ensure the continuation of high-quality care for primary care patients.

While implementing such a programme may present challenges for some practices—both organisationally and financially—it is considered a necessity. This raises the question of how, in the future, appropriate resources and support will be provided at regional and national levels through higher education institutes, training hubs and the AP school, including the potential publication of a nationally recognised primary care credential.