Ophthalmology is the busiest NHS specialty, with attendance continuing to rise (Greenwood et al, 2020; Gunn et al, 2022; NHS England 2023a). The specialty has one of the highest treatment backlogs, accounting for 10% of the total NHS waiting lists (NHS England, 2023b). The most recent ophthalmology workforce census by the Royal College of Ophthalmologists (RCOphth) (2023) reported large-scale staffing shortages as a serious problem in the UK in the aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic, while the previous census (RCOphth, 2018) identified that 230 consultant posts would be required to meet the rising demand for ophthalmology services.

The capacity and demand gap continues to widen with several factors playing a part—the ageing population; the diabetes epidemic; and the low numbers of ophthalmologists, especially in some specialist fields such as paediatrics (Government Office for Science, 2016; RCOphth 2023b). By 2050, the number of people in the UK with sight loss is expected to double (Office for National Statistics, 2015). An estimated 200 patients in the UK experience significant loss of vision every year, secondary to appointment delays (RCOphth, 2017a). These factors, together with the rapid expansion of diagnostic and treatment possibilities requiring more frequent attendance (Hingorani, 2019), mean that a greater workforce is needed to meet clinical ophthalmology demands. Paediatric ophthalmology is cited by a third of units as having the most significant backlog (RCOphth, 2023c).

In 2017, RCOphth launched ‘the way forward’ project, proposing the training of non-medical eye healthcare professionals as a strategy to manage increasing demand. Greenwood et al (2020) reported on many innovative roles using non-medical eye professionals across the ophthalmic workforce.

The orthoptist's role predominantly expands into paediatric and glaucoma care, as well as undertaking procedures such as botulinum toxin and intravitreal injections, while nurses play a major role in cataract, glaucoma, age-related macular degeneration (AMD) and emergency clinics (Greenwood et al, 2020). The role of optometrists has extended to performing YAG lasers, glaucoma and diabetic retinopathy screening clinics, as well as AMD and paediatric clinics (Greenwood et al, 2020).

Within the ophthalmic community, professional scoping exercises differentiate between extended roles, enhanced practice, advanced practice and consultant level practice. Generally, an extended role is considered to be task-based, involving limited decision making with some level of autonomy. The role would not require formal development at a Master's level, only local, regional, or continued professional development (CPD) training (Greenwood et al, 2020).

The Ophthalmic Practitioner Training Programme (RCOphth, 2023d), previously the Common Clinical Competency Framework (OCCCF), is an ophthalmology-specific initiative to bridge the capacity and demand gap. This programme, aimed at upskilling orthoptists, ophthalmic nurses and optometrists in cataract, glaucoma, acute care and medical retina, is delivered at three levels, with level three aligned to the clinical pillar of the ACP framework.

Advanced clinical practice in ophthalmology is emerging in several specialist areas. In contrast to extended roles, the advanced clinical practitioner (ACP) workforce is founded on four pillars of practice as set out in the Health Education England (HEE) multidisciplinary framework: clinical practice, leadership, education and research (HEE, 2017). ACP roles require key skills such as evidence-based practice and patient-centred decision making, modernising care pathways and dealing with complexity.

NHS England (formerly HEE) describes the ACP workforce as ‘healthcare professionals, educated to Master's level or equivalent, with the skills and knowledge to allow them to expand their scope of practice to better meet the needs of the people they care for’. Trainee Advanced Clinical Practitioners (tACPs) undertake a combination of work-based and academic learning at Master's level. Healthcare professionals who achieve ACP accreditation are expected to initiate and lead on a range of interventions, including assigning medicines and therapies, demonstrating a critical understanding of their level of responsibility and autonomy, and knowing when to seek help.

ACPs should also engage in research activity, critically appraising and synthesising relevant research, identifying gaps in evidence base and its application to practice, auditing and evaluating their own and others' clinical practice. This is key to distinguishing an ACP role from an extended role (HEE, 2017).

Advanced clinical practice in the UK began with nurses developing this role in the 1970s, with the extension of the concept to the allied health professionals (AHPs) workforce in the late 1990s and early 2000s (Royal College of Emergency Medicine, 2022). While the majority of ACP roles are held by nurses, the number of AHPs developing as ACPs is growing (Stewart-Lord et al, 2020). Griffin and McDevitt (2016) reported high patient satisfaction rates in relation to ACP services, while O'Keeffe et al (2013) discovered high job satisfaction rates among ACPs in the nursing community. Hooks and Walker (2020) found that ACPs in acute and primary settings in one region of England felt their role exceeded simply undertaking extended roles. ACPs and managers reported improved service quality and timing, with positive patient acceptance (Hooks and Walker, 2020).

Marsden et al (2010) compared advanced practice in ophthalmic nursing in the UK and New Zealand. While policies have been implemented in New Zealand to support the nurse practitioner role, the number of nurse practitioners remains low because of the lengthy and challenging validation and registration process. The absence of clear policy on advanced practice roles in the UK has allowed a variety of roles to emerge in response to health needs. This led to a confusing array of titles and payment structures (Marsden et al, 2010). Czuber-Dochan et al (2006) also identified a lack of clarification regarding roles, job titles, qualifications and pay bands in advanced practice in nursing as a significant barrier (Czuber-Dochan et al, 2006).

Other barriers to the implementation of advanced clinical practice in these professions have also been reported, with Pulcini et al (2010) documenting opposition from medical professionals as a significant barrier. Concerns regarding the change in workload, possible lack of patient acceptance, as well as professional body resistance (Higgins et al, 2013) were also reported. The positive impact of advanced clinical practice in other sectors of medicine could be replicated in ophthalmology if the identified barriers are mitigated.

Regionally, flexible advanced clinical practice services are needed, and regional faculties for advancing practice have been established to pioneer workforce transformation and drive collaborative change at a local level. The seven faculties aim to support new care pathways, improve patient safety and access to practitioners, and provide value and efficacy (HEE, 2022). Advanced clinical practice Master's programmes to address priority workforce areas are emerging in the UK. In order to craft a curriculum for a new programme in paediatric ophthalmology at the University of Sheffield, survey responses were collected from paediatric ophthalmologists and non-medical eye care professionals (orthoptists, optometrists and ophthalmic nurses).

Aims

The aim was to establish clinical curriculum areas for the new MMedSci ACP ophthalmology (paediatrics) programme, introduced by the University of Sheffield in 2021 (University of Sheffield, 2021) for current and future paediatric ophthalmology service needs and ACP workforce delivery.

Methods

The academic staff in ophthalmology and orthoptics at the University of Sheffield developed a survey to identify paediatric ophthalmology curriculum areas needed for the new potential ACP role in paediatric ophthalmology. The online survey (a Google form, provided in supplementary information) was digital and self-administered. Four populations were sampled and the survey was shared within each profession as widely as possible.

The survey was distributed to paediatric ophthalmologists to identify clinical areas where a paediatric ophthalmology advanced practitioner could relieve the clinical burden. It was also sent to hospital optometrists, orthoptists and ophthalmic nurses to determine areas for upskilling if they wished to become paediatric ophthalmology ACPs. Additionally, the survey gathered views and understanding of the ACP role.

The survey was distributed through appropriate professional bodies between October 2020 and March 2021 to the following email and distribution lists and networks:

The questionnaire consisted of 12 open- and closed-ended questions (3 mandatory), regarding ACP practice and a possible ACP curriculum in paediatric ophthalmology. Mixed question formats, including multiple choice and comment boxes, were used as well as questions using the 5-point Likert scale that allowed participants to express a range of opinions. The questions were written with the intent to identify the skills needed for the paediatric ophthalmology advanced practitioner professional qualification, in order to streamline effective clinical pathways. Efforts were made to avoid leading questions and to use clear language.

Ethical approval

The research was approved by the University of Sheffield, Faculty of health ethics committee and was conducted between September 2020 and January 2021. An introductory paragraph explained that, by completing the questionnaire, participants consented to their data being used anonymously and for the purpose of the research. This research adhered to the declaration of Helsinki. Anonymous data were gathered from the Google form results and exported to Excel for analysis.

Participants

A total of 92 questionnaires were collected. The majority of respondents were orthoptists (50 responses, 54.3%), followed by ophthalmologists (25 responses, 27.2%), ophthalmic nurses (10 responses, 10.9%) and optometrists (7 responses, 7.6%). The responses came from 81 different NHS trusts across the UK as represented in Table 1.

| Region | Profession | Scale | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Orthoptist | Optometrist | Ophthalmic nurse | Paediatric Ophthalmologist | |||

| North West of England | 6 | 1 | 1 | 3 | ||

| North East of England | 9 | 5 | 2 | 4 | ||

| Midland of England | 9 | 0 | 2 | 3 | 0 | |

| South East of England | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1–2 | |

| South West of England | 7 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 3–4 | |

| East of England | 2 | 0 | 2 | 4 | 5–6 | |

| London | 4 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 7–8 | |

| Wales | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 9+ | |

| Scotland | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | ||

| Northern Ireland | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Ireland | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| No answer | 7 | 1 | 1 | 4 | ||

| Total | 50 | 7 | 10 | 25 | ||

Results

Areas of specialist interest

The most common areas identified as part of the current practice of paediatric ophthalmologists as well as non-medical eye care professionals are presented in Table 2. There was a difference between the base professions of the eye care professionals and the areas of extended work they regularly undertook. The areas most commonly identified as part of orthoptists' areas of practice were strabismus, nystagmus, vision screening, paediatric cataracts and low vision, respectively.

| Area currently working in | Area thought useful to be included in advanced clinical practice course | Frequency* | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical condition | Paediatric ophthalmologists (%) | Non-medical eye care professionals (%) | Paediatric ophthalmologists (%) | Non-medical eye care professionals (%) | Scale | |

| Blepharitis | 100 | 14.93 | 84 | 62.69 | High | |

| Botulinum toxin | 56 | 10.45 | 16 | 38.81 | Low | |

| Chalazion | 96 | 19.4 | 88 | 71.64 | High | |

| Conjunctivitis | 100 | 13.43 | 76 | 67.16 | High | |

| Cortical visual impairment | 84 | 10.45 | 28 | 65.67 | High | 0-19.9 |

| Disc and neuro screening | 92 | 19.4 | 68 | 74.63 | High | 20-39.9 |

| Eye casualty/emergency setting | 80 | 28.36 | 52 | 73.13 | High | 40-59.9 |

| Glaucoma/buphthalmos | 52 | 11.94 | 16 | 50.75 | Low | 60-79.9 |

| Juvenile idiopathic arthritis screening | 88 | 20.9 | 92 | 65.67 | High | 80-100 |

| Low vision | 36 | 29.85 | 72 | 40.3 | High | |

| Nasolacrimal duct obstruction | 100 | 19.4 | 80 | 70.15 | High | |

| Neurofibromatosis type 1 | 84 | 19.4 | 72 | 62.69 | Low | |

| Nystagmus | 84 | 56.72 | 20 | 71.64 | Medium | |

| Paediatric cataract | 76 | 34.33 | 20 | 70.15 | Low | |

| Retinoblastoma | 40 | 16.42 | 12 | 56.72 | Low | |

| Strabismus | 96 | 74.63 | 60 | 67.16 | High | |

| Screening services | 48 | 55.22 | 84 | 49.25 | High | |

The figure presented is given as a percentage and the intensity of the colour denotes the most popular areas.

Ophthalmic nurses were mostly working in eye casualty, vision screening, paediatric cataracts and retinoblastoma, while optometrists identified vision screening and strabismus as the most common areas of work. In the free space given for respondents to identify other clinical conditions for the paediatric ophthalmology ACP workforce, suggestions included:

The frequency of each condition, as seen within the paediatric ophthalmology clinic, is shown in Table 2, where it is presented as high, medium or low. These categorisations, together with areas paediatric ophthalmologists reported as frequent conditions (within the survey) were determined by a prevalence cohort study by Cumberland et al and the Millennium Cohort Study Child Health Group (2010).

Barriers to implementation

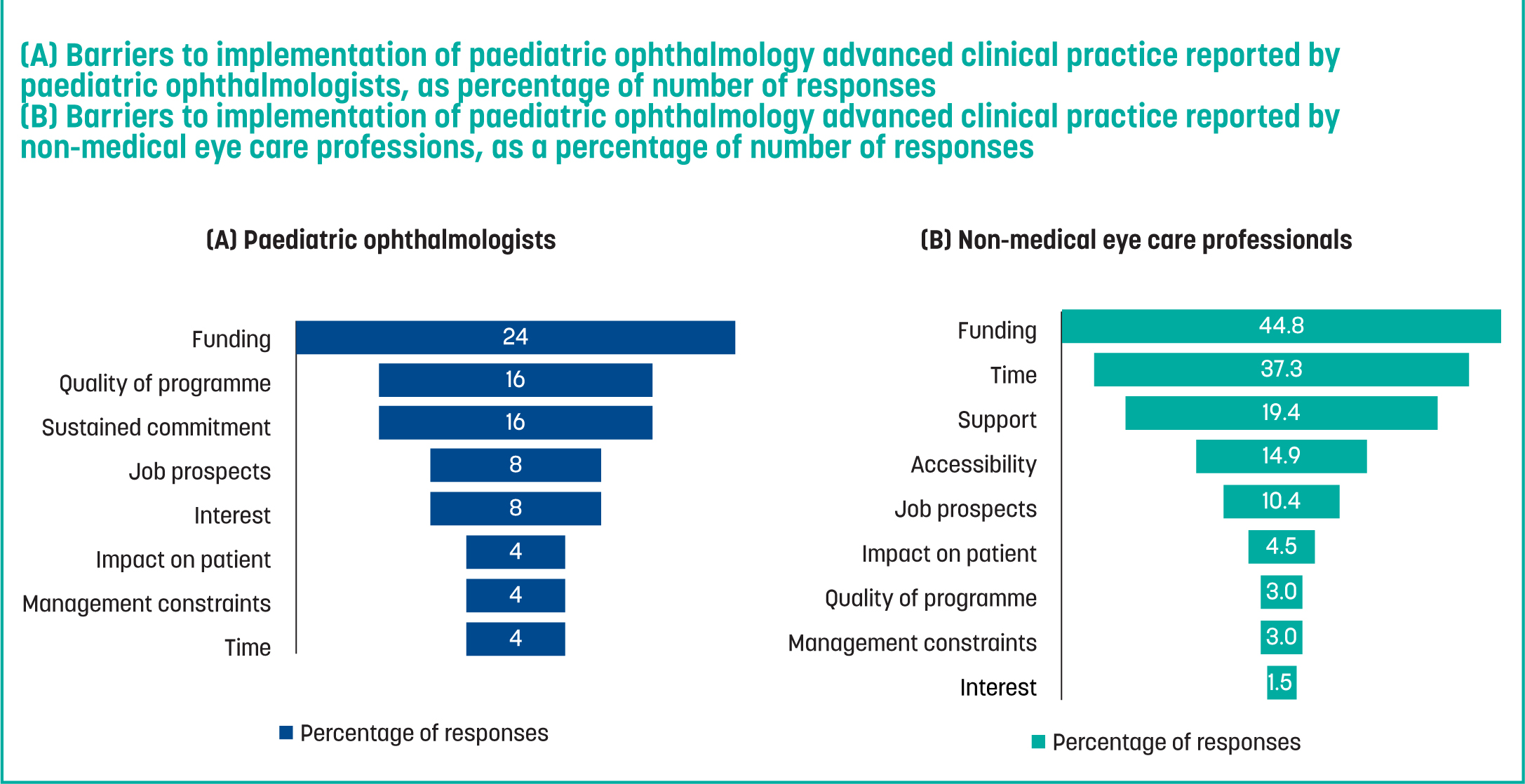

While the largest barrier for both paediatric ophthalmologists and eye care professionals was funding, the secondary and tertiary barriers identified by paediatric ophthalmologists were the level and quality of the programme and sustained commitment. For non-medical eye care professionals, these were time and support (Figure 1).

Some participants mentioned the importance of online learning, while others emphasised the importance of a practical element of learning and assessment. Furthermore, several respondents suggested there would need to be motivations for undertaking a course, such as ACP accreditation and opportunities for career progression.

Practitioner perceptions regarding the understanding of the role of ACP in paediatric ophthalmology

Common themes from orthoptist responses were upskilling and taking on additional roles that would enable them to work independently while reducing the workload for ophthalmologists. Common themes from paediatric ophthalmologists for the ACP role were that non-medical eye care professionals should take on more roles, allowing ophthalmologists to manage higher risk patients. A minority of the respondents mentioned the importance of research, leadership and education in ACP, while the majority of comments focused on the clinical aspects.

Other skills needed for the advanced clinical practitioners in paediatric ophthalmology in future years

When asked what further skills would be needed by ACPs in paediatric ophthalmology, the answers were: refraction, independent prescribing, interpretation of imaging and diagnostics, slit lamp techniques and research skills.

Interest in the course

The majority of all the eye care professionals who participated in the study expressed an interest in an advanced clinical practice course in paediatric ophthalmology, with 79.3% indicating it would be ‘likely’ or ‘very likely’ for them to enrol or suggest enrolment to other team members. It was very clear that enrolment would rely on funding, with 85.8% of respondents reporting that they are ‘dependent’ or ‘very dependent’ on funding.

Curriculum areas

After careful evaluation of Table 2 and discussion with colleagues working in these specialist areas of care from around the UK, the following paediatric ophthalmology curriculum areas were chosen for the advanced clinical practice paediatric ophthalmology curriculum:

Discussion

The survey results provided key insights into the paediatric ophthalmology clinical areas currently within the scope of practice for paediatric ophthalmologists and current eye care professionals (orthoptists, optometrists and ophthalmic nurses), as reported in Table 2. Unsurprisingly, a higher percentage of paediatric ophthalmologists reported working with each of the conditions listed, when compared to the eye care professionals, showing the area and scope of work that currently largely remains with ophthalmologists.

Many areas were identified as suitable for practice for the new paediatric ophthalmology ACP workforce, as evident in the high percentages for a broad curriculum. The areas with lower reported involvement from ophthalmologists, allowed the authors to determine the less clinically burdensome areas. However, for all of the areas reported, there was further work to do. For instance, conjunctivitis needed to be further categorised into BKC and VKC. Glaucoma, although not a high area of demand, needed to be differentially diagnosed from other similarly presenting conditions.

In general, the response rate was low and perhaps the timing of the survey's distribution (post COVID-19) was a factor, with response rate varying for different professions. Only seven responses were collected from optometrists and this might not be representative of the general view of optometrists across the UK. Similarly, 10 responses were collected from ophthalmic nurses. In addition to clinical pressures and workloads, there may have been other reasons why eye care professionals and ophthalmologists did not respond, such as not yet being comfortable with the definition of the level of practice of an ACP—in support of this theory, several respondents referred to ACP as extended roles. Only a few respondents mentioned leadership, education and research as part of their understanding of an ACP role.

A variability in ophthalmology role terminology was also noted by Greenwood et al (2020). There is a need for greater ophthalmology awareness and understanding of the ACP and related roles. Steward-Lord et al (2020) emphasised the importance of promoting the understanding of ACP roles across the workforce, as well as the general public.

The majority of respondents identified funding as the main barrier, prohibiting them from enrolling in an ACP course. The emerging need of ACP roles is being felt in different workforces across the UK. To meet the increasing service demand, the NHS Long Term Plan (2019) and the NHS Long Term Workforce Plan (2023) emphasise the importance of investing in the ACP workforce to contribute to the workforce transformation agenda (NHS England 2019a; NHS England 2019b). In 2020, the NHS People Plan highlighted the increase in innovative roles, contributing to valuable clinical support in areas such as critical care, while still underscoring the need for additional ACP training. In 2020–21, the plan was to fund a further 400 healthcare workers for ACP training to build on the success that was already seen as a result of increasing ACP roles to improve the quality of care offered by multidisciplinary teams (NHS England, 2020). Plans to increase funding to further practitioner training, as in ACPs via Master's courses, have already been published (NHS England, 2022).

The respondents mentioned other aspects that would affect their decision to enrol, which are common to ACPs from nursing and several AHPs. Several respondents stated that the availability of clinicians to support and supervise was a key factor. A study by Fothergill et al (2022) found that there was no consistency in supervision and guidance structures, with only 32% of ACP respondents reporting a formal structure for their supervision. To enhance ACP career progression and professional development, it is important to provide the required support and high-quality supervision. Establishing standardised supervision approaches is essential, to which end the NHS England has published workplace supervision guidance for advanced practice (NHS England, 2022).

Some orthoptists and an ophthalmic nurses reported that the availibilty of consultant support would also influence their decision. According to Keating et al (2010), nurse practitioners felt a lack of understanding and support from medical professionals. However, in Kerr and Macaskill's study (2020), participants perceived doctors as being more positive and understanding towards advanced nurse practitioners' roles and services. This might indicate a trend towards increasing willingness from ophthalmologists to delegate clinical work to ACPs. The majority of paediatric ophthalmologists within this study showed support towards the introduction of ACPs in this area of specialty. Some ophthalmologists did note that only low-risk cases should be managed by non-medical professionals, while others were open to the possibility of assessment and management of high-risk cases, but with consultant supervision and input.

One aspect not mentioned by survey participants, but a recurring theme in other studies, was the lack of standardisation of job titles, description of job roles and frameworks. Fothergill et al (2022) highlighted the lack of standardisation in ACP roles, specifically variations in job titles, educational backgrounds, scopes of practice, job descriptions, as well as lack of governance structures leading to inconsistent ACP frameworks (Fothergill et al, 2022). Similarly, Steward-Lord et al (2020) found an inconsistent ACP infrastructure within AHPs, with considerable discrepancies in levels of qualification and evolution of roles (Steward-Lord et al, 2020).

The introduction of ACPs in the ophthalmic community does not negate the need for extended roles, as these are highly valuable in meeting demand. It should be recognised that not all practitioners will want to undertake a Master's degree. NHS England has outlined the roadmap for multi-professional progression as follows: core practitioner, enhanced practitioner, advanced practitioner and consultant practitioner (NHS England, 2022).

Educational possibilities vary and include local training for an extended role to Master's and doctorate levels of qualification for a non-medical consultant role. With the growing capacity and demand gap in ophthalmology both nationally and internationally, there is a need to upscale the recruitment and retention of the workforce into ACP roles in ophthalmology. The ophthalmology ACP profession is still evolving, with various areas of specialisation expanding. To support this growth, there is a need for professional scaffolding, networking, and evidence demonstrating the impact and influence of these roles to further develop the ophthalmology ACP community.

Conclusions

This research has identified the curriculum development process for the clinical role of ACP in paediatric ophthalmology. The heavy clinical ophthalmology burden needs national-scale solutions, to distribute the increasing workload to a capable workforce. While the perception and knowledge of ACP is improving in general, there is still work to be done, particularly in the context of ophthalmology and specialist training pathways. Funding and access to supervision are two key areas which may facilitate the uptake and success of this workforce.