The healthcare landscape in Singapore is dynamic. Given the country's rapid advancements in healthcare technology, there is an increasing demand for specialised skills in managing specific cancer cases within radiation therapy practice. This demand has created further opportunities for radiation therapists (RTTs) to address service gaps, such as patient treatment timeliness and treatment quality, and to increase job satisfaction, as highlighted in studies by Lim et al (2020) and Wong et al (2021). Therefore, as regional health systems in Singapore strive to remain contemporary, there is a need to broaden the roles of existing allied health professionals (AHPs) to meet service demands.

This study centred on advanced practice radiation therapy (APRT) roles in Singapore and explored the comparable roles of the UK advanced practice radiographer (UKAPR), specifically in England, UK. This examination considered operational implementation and can serve as a reference for other countries aiming to enhance their services. This collaboration, which was conducted as a joint operation between the UK and Singapore, offered mutual benefits, including the fostering of a diverse cultural and knowledge exchange, thereby encouraging innovative approaches and expanding the scope of both countries' APRT roles. A team of three experts from the National University Health System (NUHS) visited the UK in February 2023 (the chief RTT, senior principal RTT and a senior consultant clinical oncologist). The main goal of this visit was to investigate the scope of practice, educational pathways, training aspects and career advancement possibilities linked with UKAPR roles. The intention was to learn how to establish comparable positions in Singapore, thereby enhancing service delivery within its healthcare system. The secondary objective was to use the knowledge gained to devise and, if feasible, implement analogous structures in both the NUHS and broader landscape of Singapore's healthcare sector. This required the researchers to have a comprehensive understanding of the RTT competencies, be able to contextualise them in terms of consultant practitioner and enhanced practitioner roles, and address legal considerations and navigate framework-related matters.

Background

In response to the growing complexity of cancer cases and advancements in healthcare technology, specialised expertise in radiation therapy practice has become pertinent (Wong et al, 2021). Traditionally, RTTs focused on delivering treatments guided by clinical oncologists. However, evolving healthcare needs and regional health system aspirations have led to an expansion of roles for AHPs. Advanced practice (AP) roles, including advanced practice radiographers (APRs) in radiation therapy, have emerged to meet the demand for specialised skills (Stewart-Lord et al, 2020; Khine and Stewart-Lord, 2021; Olivera et al, 2022).

In 2017, Health Education England (HEE), NHS England (NHSE) and NHS Improvement collaborated to establish a national framework for advanced clinical practice (NHSE, 2017a). This initiative was driven by the challenges outlined in NHSE's (2014) Five Year Forward plan and a subsequent NHSE document, Next Steps on the Five Year Forward View (2017b), which addressed workforce gaps within the NHS in England. These documents acknowledged the strain on the healthcare workforce due to rising service demands. The multi-professional framework for advanced clinical practice provided a universally accepted definition applicable across professions and contexts. This standardised definition of advanced clinical practice aimed to address disparities, ensuring consistency across professions and levels of practice. The Society and College of Radiographers (SCoR) subsequently published specific guidelines in their education and career framework, outlining the knowledge, skills and attributes of advanced clinical practice in radiography (SCoR, 2022).

Recognising the need to bridge clinical gaps and enhance service efficiency in Singapore, the NUHS team explored the implementation of AP roles within radiation therapy. NUHS represents one facet of Singapore's health cluster, alongside SingHealth and the National Healthcare Group. Drawing insights from the well-established AP roles in the UK, the NUHS team sought to understand scope of practice, educational requirements and career pathways associated with these roles. Challenges identified in the UK included, but were not limited to, the misalignment of job descriptions, which hindered the fulfilment of AP roles and consistency in pay scales (Harris et al, 2021).

The outcomes of this study will guide the development and implementation of AP roles within the NUHS. Leveraging knowledge from the UK visit, the NUHS aims to empower RTTs to effectively manage complex cancer cases and address Singapore's evolving healthcare needs. The insights gained from this endeavour will contribute significantly to enhancing the capabilities of RTTs and improving cancer care in Singapore overall.

Methods

Pre-visit planning

The collaboration between the NUHS and a higher education institute in England, UK, began in early 2022, where a 1-week scientific visit was proposed. This visit was set to be funded by the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA), an independent agency within the United Nations, which is pivotal in supporting nuclear technologies, including radiotherapy, for medical purposes. The planning and execution of viable strategies within the designated timeframe involved extensive discussions among the lead author, who acted as the coordinator, and clinical centre practitioner leads and subject matter experts. Key considerations included:

The objective was to gain valuable insights into several aspects of the UK's radiography practices, including the scope of AP, educational prerequisites, training pathways, career development possibilities similar to UKAPRs and relevant governance structures. Consequently, stakeholders were selectively invited based on the capacity to complete these objectives.

The itinerary for the UK scientific visit was carefully curated to optimise knowledge exchange and collaboration. It comprised:

Collaboration and research

Attendees of the inaugural meeting in the UK comprised of professional officers, an academic and experts from Singapore, and covered deliberations on various facets within the domain of advanced clinical practice (ACP) roles. The discussions encompassed topics such as governing structures, educational aspects, career frameworks, legislative considerations and recent advancements within the radiography profession. During the meeting, essential qualitative data were collected through the interactions that occurred between the participants. Following the meeting and the week-long visit to various clinical and academic centres, a post-visit questionnaire was distributed to the team of visiting experts from Singapore. The purpose of this questionnaire was to systematically gather information pertaining to participants' perceptions, opinions and reflections on the visited sites. The survey comprised of a set of 15 questions formulated by the academic team to align with the study's precise objectives. These aimed to grasp the structural essence of the advanced practitioner radiographer role in the UK. The study sought to gauge perceptions on the feasibility of establishing AP roles in Singapore and assessing the infrastructure viability within its NUHS. This included capturing their intellectual perspectives and agreement on decisions, as well as exploring thoughts and identifying what they saw as potential opportunities.

The collaboration and strategic planning allowed the researchers to explore various aspects related to AP in radiotherapy in both countries. The engagement with key stakeholders, including professional bodies, healthcare providers and academics, provided valuable insights into current UK practices, educational requirements and future development of AP roles.

Data collection and analysis

The evaluation of the scientific visit's impact on collective outcomes was conducted through a formative approach. To gauge the influence of the visit on joint outcomes, an unrestricted open-ended self-reported questionnaire was administered to all three participants following the visit. The combined results encapsulated the participants' newfound insights into the viability, applicability and developmental implications linked to evidence-based clinical role advancements. It also covered significant medical directives, aspects influencing practice guidelines and the potential for collaborative prospects between Singapore and the UK for advancing professional roles and technology initiatives in the future. Authors RJ and RK assessed meeting minutes and conducted thematic analysis to derive overall themes (Braun and Clarke, 2006).

The questionnaire used in this study adopted a standalone qualitative design, which was intended to elicit comprehensive and descriptive responses from the participants post-visit. It consisted of 15 open-ended questions that aimed to explore various dimensions related to the outcomes of the visit.

Findings

Overall outcomes

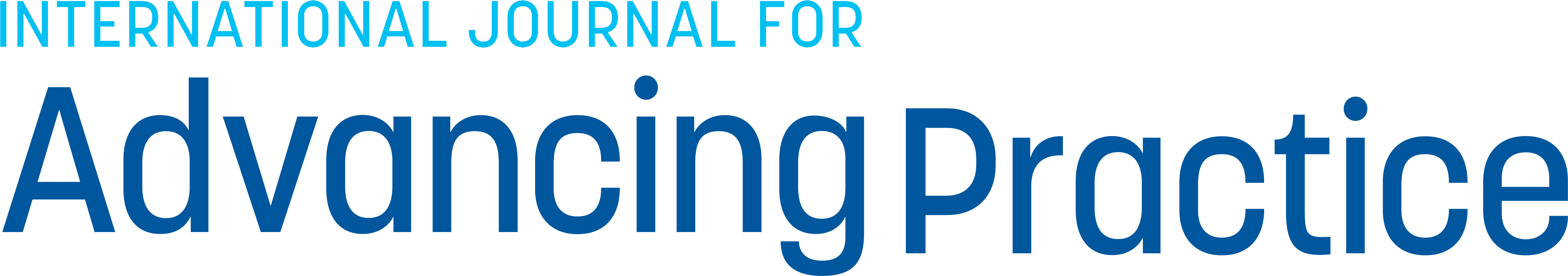

Knowledge exchange and meeting

The findings obtained through the two-part methodology (consultation meeting outcomes and a post-visit questionnaire) offered insightful perspectives that not only brought clarity to the subject, but also provided valuable indications on how the scientific visit could support Singapore's healthcare reform concerning APRT. This was through its implications being extended to the broader healthcare landscape. The visit's opening consultation meeting comprised primary knowledge-sharing data. The data revealed several critical points of discussion related to professional, legal and governance themes. These are summarised in Figure 1. In line with the Venn diagram depicted in Figure 1, key discussion points from the consultation meeting are further elaborated and grouped into appropriate themes in Table 1.

| Theme | Aspects |

|---|---|

| Professional | Guests are urged to explore a comprehensive range of significant reform documents starting from the year 2000, encompassing essential papers such as the NHS Plan (NHS England, 2000), the Department of Health's Radiography Skills Mix report (Department of Health, 2003) and the current education and career framework for the radiography workforce (Society and College Radiographers (SCoR), 2022) |

| Legal | Although the Health Care Professions Council (HCPC) regulatory body in the UK is legally responsible for radiographers' standards of conduct and performance (meeting specific educational qualifications, demonstrating competence and maintaining continuing professional development), they regulate the profession rather than levels of practice |

| Governance | While practitioners must exhibit advanced proficiency across four fundamental domains—expert clinical practice; professional leadership and consultancy; education, training and development; and practice and service development, research and evaluation—according to the UK's education and career framework for the radiography workforce (SCoR, 2022), fulfilling the local clinical practice competency sign-off standards set by clinical oncologists remains a requisite for UK advanced practice radiographers. This involves ensuring educational standards are met, enabling learners to bridge theory and practice, while fostering critical thinking skills |

The themes highlight the key elements necessary for crafting a governance structure for APRT and balancing flexibility to accommodate varying rates of role development across Singapore's health clusters, while ensuring clarity and definition in practice parameters. This framework should support profession-specific initiatives and be informed by the complexities observed in the UK. These insights should be used to shape a more comprehensive regulatory framework that caters to diverse needs and fosters inclusivity.

Post-scientific visit questionnaire

The next phase of the methodology involved the administration of a post-scientific visit feedback questionnaire. Analysis of the feedback revealed that the advancement of AP in Singapore's radiotherapy practice was at an early stage. Challenges with AP roles were identified/highlighted by the questionnaire findings. Additionally, several facilitators were recognised, notably the identified service requirements for these roles and the availability of professional development opportunities for RTTs. Delegates highlighted that the scientific visit significantly enhanced their comprehension of the broader concept of advanced practice, yielding distinct themes: conception, challenges, enablers, and insights.

Thematic analysis

Conception

The feedback provided by the Singaporean visiting experts acknowledged that within the National Cancer Centre, Singapore (comparable hospital facility to the NUHS), AP was still in its infancy. Several sub-clinical sites were initially identified as part of plans to develop AP roles. The head and neck specialism was selected by the radiation oncologists and RTTs as the first field to develop an AP role for, and a planned training programme structure was developed alongside the role. Some of their key responses were:

‘They first started with the head and neck APRT role, where a structured 1-year residency training programme was developed. The programme consisted of structured lectures and clinical practice-based modules, where APRT residents receive structured mentoring under a mentorship programme. A competency and assessment framework was set up to assess the core competency areas.’

Moreover, the analysis of the survey also acknowledged the importance of stakeholders to aid in the conception of AP roles:

‘We would need to include oncologists in other institutions, [as well as] hospital senior management [and an] allied health regulating body’.

Challenges

The post-visit feedback also acknowledged several challenges in the implementation of AP roles in Singapore. These included areas such as funding issues and the unfamiliarity of AP roles:

‘There is a lack of awareness on the advance role of RTT, no funding to support the advance role development for RTT, and no national guidelines to support advance practice and remuneration for advance roles.’

In addition, the feedback also highlighted the potential for patients to be disinclined to accepting AP practitioners/their roles:

‘Patients may not be aware or accept an RTT to lead the treatment review. They may still prefer to see a doctor.’

The visitors were equally keen to acknowledge solutions to the challenges if the APRTT role was successfully adopted by the workforce:

‘We need to educate and to communicate with patients in advance that the care model is a team effort, consisting of both RTTs and doctors.’

‘The funding will mainly be the hospital training funds. We are currently exploring opportunities to seek funding from other national skill training or cancer society's funding.’

Enablers

Several enablers were also acknowledged, specifically the service needs of such roles and professional development opportunities for RTTs:

‘The gaps are in palliative, head and neck cancer, breast cancer sites and image guided radiotherapy and advance technology and techniques.’

‘The development of APRT roles can also help to promote the profession, as RTTs are now able to undertake more roles and responsibilities.’

Alongside those mentioned above, the delegates were keen to highlight that the enablers can also provide benefits such as the positive impact on patient care:

‘The development of APRT role can help to improve patients' experience and care during their treatment.’

Insights

The delegates commented on how the scientific visit provided them with a greater insight into the concept of AP, which was seen as highly beneficial:

‘The visit has provided us with a better understanding of the development of the APRT in UK, and the different roles and responsibilities of the APRT.’

Moreover, the visit reportedly provided them the opportunity to learn from others engaged in AP, with particular reference to the work conducted in the UK:

‘There are many areas that we can learn from the work done by UK professional bodies. Some of the areas of practice include the development of a professional development framework, as well as guidelines for the regulation of advance practice, roles of professional bodies and clinical professional development.’

‘There are lot of things that we can learn from the UK experience in APRT.’

Discussion

Uniformity of standards

Recognition of radiotherapy's efficacy in treating oncology patients has expanded globally (Duff ton et al, 2019); the development of RTT roles in Singapore has been driven by this increased demand for healthcare (Allied Health Professions Council (AHPC) Singapore, 2023). This has led to the acknowledgment and emergence of AP roles, shaping related job descriptions and scopes of practice. To demonstrate RTT proficiency in AP, Sin et al (2021) compared the assessment of side effects in patients with nasopharyngeal cancer between radiation oncologists and APRTs in head and neck radiation therapy working within the SingHealth health cluster. The findings revealed a strong agreement in grading side effects, indicating the feasibility and potential contribution of APRTs in patient assessment, and emphasising the importance of timing for the launch of APRT in Singapore's practice. The initiation, however, requires support from national workforce guidelines and frameworks, which are yet to be formalised by the country's government organisation (Ministry of Health, 2023). Contextual differences and cultural changes may be the cause for hesitation in deviating from existing norms, along with concerns related to risk aversion towards the accelerated adoption of APRT roles within NUHS and across other health clusters. The AHPC in Singapore, operating under the Ministry of Health, regulates the behaviour and ethical standards of registered AHPs nationally, in line with legislation, such as the AHPC Act (2011). This Act oversees registration, certification issuance and training standards, and maintains a comprehensive register of AHPs across Singapore, akin to the role of the Health Care and Professions Council (HCPC) in the UK.

Global perspectives and contextual challenges

It is challenging to offer a unified global view on AP in radiotherapy due to differences in educational systems, workforce dynamics and resource availability (Duff ton et al, 2019). Despite this, various countries beyond the UK have effectively established policies and frameworks that support AP roles. For instance, entities such as the Australian Society of Medical Imaging and Radiation Therapy (ASMIRT) and the Canadian Association of Medical Radiation Technologists (CAMRT) have successfully integrated AP into multidisciplinary teams (MDTs) (CAMRT, 2016; ASMIRT, 2017).

Singapore's healthcare system differs from the UK's, employing a mixed approach that involves government subsidies, mandatory savings (Medisave), insurance coverage (Medishield Life) and direct out-of-pocket payments (Health Hub, 2023). Singapore's Ministry of Health may emphasise workforce development strategies that align with this mixed system, focusing on specific skill sets and training to maximise the use of these diverse financing mechanisms. Conversely, HEE, operating within the UK's NHS (now denoted as NHS England (NHSE)) may concentrate on workforce strategies tailored to a predominantly publicly funded healthcare system, crafting training programmes and workforce planning to suit the needs of a system heavily reliant on government funding and resources.

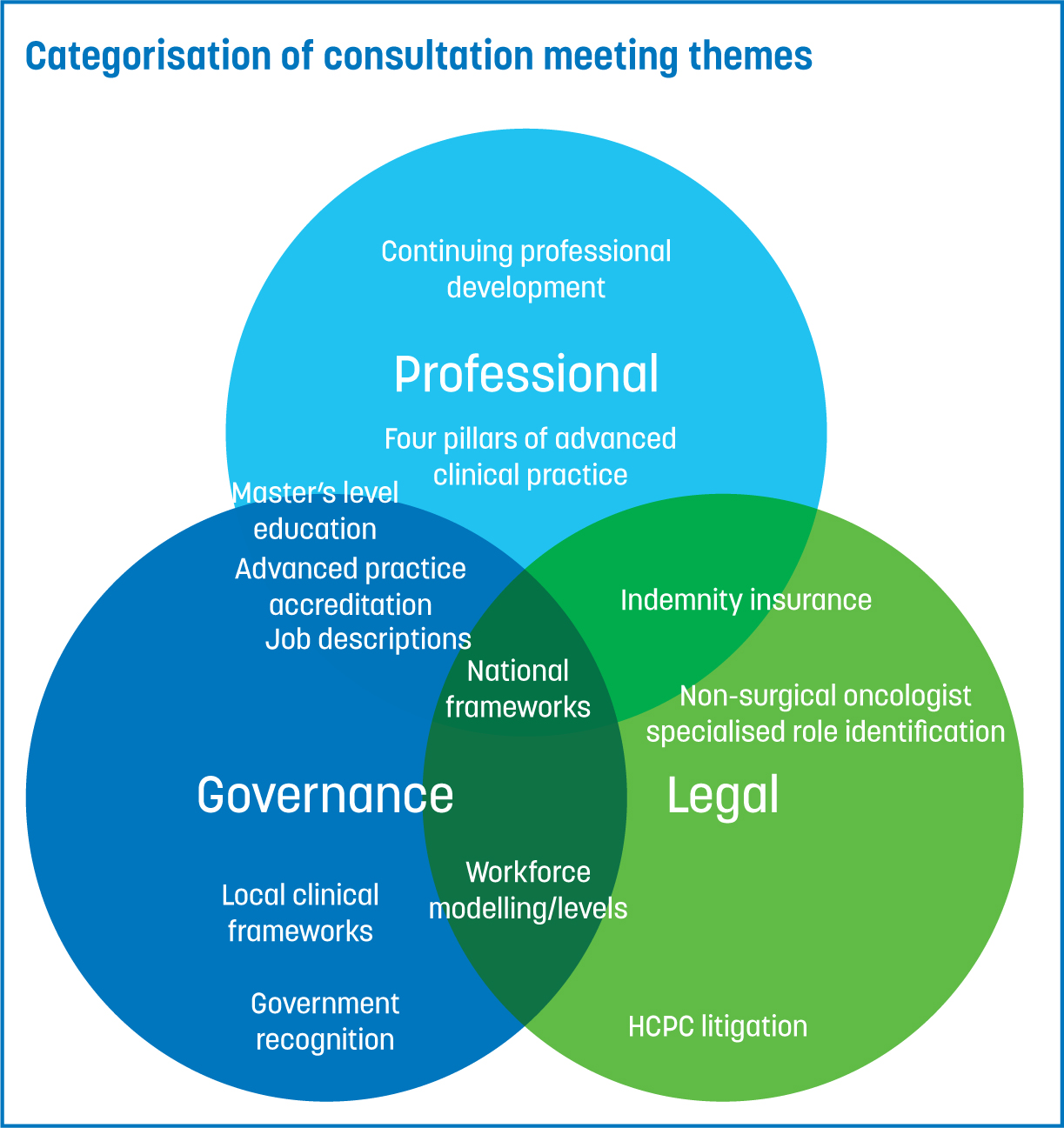

As the career framework for the UK's radiography workforce evolves, the importance of viewing AP as an integral part of a larger framework has become evident. The recognition of diverse career progressions traces back to 2003, when assistant practitioner roles were initially acknowledged by the government's radiography skills-mix report (Department of Health (DoH), 2003). Since then, there have been developments in enhanced, advanced and expert practice levels (among others), forming a cohesive pathway. This holistic approach not only influences job descriptions, but also extends to job plans, enabling hospitals and systems to strategise comprehensive career progression for practitioners. Such initiatives (Figure 2) are pivotal in developing profession-based workforce planning strategies, ensuring a consistent supply of skilled healthcare professionals (Department of Health and Social Care, 2013; NHSE, 2014). The map displayed in Figure 2 identifies the approximate point of registration towards the progression point relevant for advanced practice. This is particularly important for NUHS, as it moves towards ensuring parity among APRT pay bands and job titles. National standardisation in Singapore should be an important factor in institutional development across all health clusters.

Progression pathways

Given the absence of an AP structure in radiotherapy, efforts are underway to build a comprehensive career pathway (Lim et al, 2020; AHPC, 2023). The safeguarding of career progression levels is specifically ensconced within the protective sphere of professional titles, notably within the realms of diagnostic and therapeutic radiography. This configuration allows a certain degree of autonomy in crafting career progression pathways, which is underpinned by comprehensive research and remains responsive to nationally indicated needs (Appleyard et al, 2021).

Due to the UK's demographic diversity shaping local hospital needs, disparities in accessing UKAPR training routes have led to unequal opportunities across practice areas for CPD and career advancement. Consequently, there exists a discrepancy in the qualifications and experience held by UKAPRs. Addressing these challenges, the SCoR education and career framework (SCoR, 2022) emphasised the importance of standardised and benchmarked training routes, which involves ensuring educational standards are met; this enables learners to bridge theory and practice, as well as foster critical thinking skills. These disparities highlight potential challenges for Singapore's health systems to consider and potentially avoid.

Educational approaches

In assessing the comparative analysis between Singapore and the UK concerning the accessibility and extent of available data, notable insights can be derived by examining governmental expenditure on education. According to UNESCO (2023), while Singapore allocated 2.4% of its GDP towards education in 2022, the UK dedicated 5.3% in 2021. Despite this, accessing precise statistics pertaining to healthcare education funding for health professionals presents a considerable challenge. This dearth of data suggests a potential area for enhancement, indicating a necessity for increased investment in broader healthcare education initiatives. Notably, the realm of radiation therapy education represents a fraction of this broader scope.

Considering the lack of a formalised curriculum, the pursuit of an MSc remains paramount for UKAPRs, offering a structured educational pathway essential for APs to meet the requirements outlined in the multi-professional framework for advanced practice in England (NHSE, 2017a). Emphasising capability development, this framework underscores the necessity for practitioners to discern the required level of competence within diverse situations, rather than focusing solely on educational processes. This flexibility enables practitioners to adapt and extend their expertise according to service demands. This pursuit aligns with the accreditation criteria established by the SCoR, addressing specific service-related needs and ensuring compliance with the local competency sign-off standards set by clinical oncologists and/or experts for UKAPRs. Alternatively, achieving recognition of MSc AP equivalence involves participation in the supported e-portfolio route offered by the Centre for Advancing Practice, culminating in the attainment of a digital badge upon completion (SCoR, 2023). Nevertheless, while the SCoR's accreditation scheme involves portfolio submission for accreditation, these pathways currently function independently without integration (SCoR, 2023). However, using such viable UKAPR mechanisms is predicted to enable NHSE to increase its AP training by 46% within the next 15 years; NHSE is reportedly intending to enrol 5000 clinicians annually in AP pathways, including therapeutic radiographers (NHSE, 2023). This drive showcases the government's trust in the efficacy of training and accreditation mechanisms for the AP workforce.

Australia, along with nations such as New Zealand, seems to be actively embracing innovative educational approaches in CPD. This is evident through a range of implemented initiatives, such as the creation of a MSc AP programme that is designed to suit practitioners' needs, clinical settings and professional requisites, irrespective of a national capability framework for standardisation (Wright and Matthews, 2022; University of Otago, 2023). Given the absence of such courses in Singapore's higher education institutes, NUHS practitioners might consider exploring available international options. Alternatively, if Singapore's health systems, professional organisations and respective government bodies trust international training standards and educational alternatives, the recognised authorities in those countries leading in the APRT domain should formally recognise and support the extended scope of practice for APRT professionals in Singapore. This formal acknowledgment might play a vital role in expediting policy changes overseen by the governmental body regulating Singapore's radiotherapy profession.

Post-visit questionnaire outcomes

The findings from the post-scientific visit questionnaire outlined imperative themes—conception, challenges, enablers and insights—regarding the development of APRTs. The analysis revealed that AP was still in its early stages of progression within SingHealth, with plans to formalise AP roles across other clusters in the future. The SingHealth APRT initiative had commenced before the scientific visit discussed in this article, and consisted of a structured 1-year residency training programme that focused on head and neck specialisation, and was backed by mentoring and competency assessment frameworks. Stakeholder involvement, particularly from oncologists, hospital management and regulatory bodies, was highlighted as pivotal in shaping AP roles.

However, the initiative also faced challenges. A lack of awareness, funding, national guidelines and patient acceptance were prominent hurdles that had to be overcome. Proposed solutions included patient education about collaborative care models and exploring various funding avenues, primarily relying on hospital training funds and seeking external support.

Conversely, enablers for APRT roles encompassed identified service needs in specific cancer sites and technology advancements. The development of APRT roles was viewed as a way to expand professional responsibilities and potentially enhance patient care experiences.

Insights gleaned from the scientific visit to the UK highlighted the benefits of understanding the UK's AP model and its diverse roles and responsibilities. Learning opportunities from the UK's government and professional bodies, especially regarding professional development frameworks, regulatory guidelines and continuous learning, were acknowledged as invaluable.

Cultural context

Given the alignment in radiotherapy practices between Singapore and the UK, which have been influenced by international standardisation and the shared use of medical products for cancer treatment, it is important to acknowledge existing cultural and systemic differences between the countries' healthcare systems. Understanding these distinctions is useful for a potential integration of AP scope and for addressing current challenges. Table 2, Table 3 and Table 4 offer insight into the disparities at three key practice levels. These are:

| Aspect | Singapore | UK |

|---|---|---|

| Healthcare financing strategy | Mixed approach, including subsidies, savings, insurance and out-of-pocket payments | Predominantly publicly funded healthcare system |

| Healthcare system | Mixed system with public and private healthcare providers | NHS is publicly funded |

| Demographic diversity impact | Demographic diversity of service needs shaping local hospital needs | Disparities in accessing advanced practice radiation therapy training routes, resulting in unequal opportunities for continuing professional development and career advancement |

| Aspect | Singapore | UK |

|---|---|---|

| Hospital management/leadership structure | Varies based on individual hospital administration | Generally, follows the NHS hierarchy, led by Trust Board and Integrated Care Systems Board/Partnership Board |

| Administrative decision making | May involve a combination of local and centralised decisions | Decision making often centralised within NHS structures |

| Hospital funding mechanism | Mixed approach | Predominantly centrally funded through taxation, with limited private provision |

| Hospital size and structure | Varies; smaller and larger hospitals may have different structures | NHS hospitals follow standardised structures based on size |

| Professional indemnity | Supplied by the local hospital or health system | Supplied on a centralised basis by a national professional organisation |

| Aspect | Singapore | UK |

|---|---|---|

| Radiotherapy treatment decision making | Often involves the oncologist as the primary decision maker, with strong influence from family input | Emphasis on shared decision making, involving oncologists, clinical oncologists and patients |

| Perception of radiation therapists (RTTs) | Generally viewed as essential members of the treatment teams; strong respect for their role by the public | Recognises the central role of RTTs, often part of multidisciplinary teams, but with varying public awareness |

| Preference for doctor-led care | Traditionally, there may be a preference for being treated by doctors over allied health professionals | Generally open to receiving care from various healthcare professionals, including allied health professionals |

| Role of family in decision making | Significant family involvement in decision making; family may expect to be well informed | Values individual autonomy but recognises the importance of involving family as needed |

Systemically, the adaptation of public sector provisions in the UK, specifically in England, faces challenge due to the diverse demographics that new policies must address, especially in AP. The evolution of UK practices has been a gradual process over several years, influenced by the entirely public tax-based system of the UK NHS, where cost management is a high consideration. In Singapore's mixed healthcare system, encompassing both public and private provision, establishing a unified approach across hospitals may be comparatively more manageable.

Singapore's hospital leadership structure varies, contrasting with the UK's NHS-centralised hierarchy. While this might pose challenges in aligning a collective vision among Singaporean hospitals, the country's smaller size and fewer facilities within the three health clusters could facilitate accelerated change to support AP policy change, particularly in response to evident service demand.

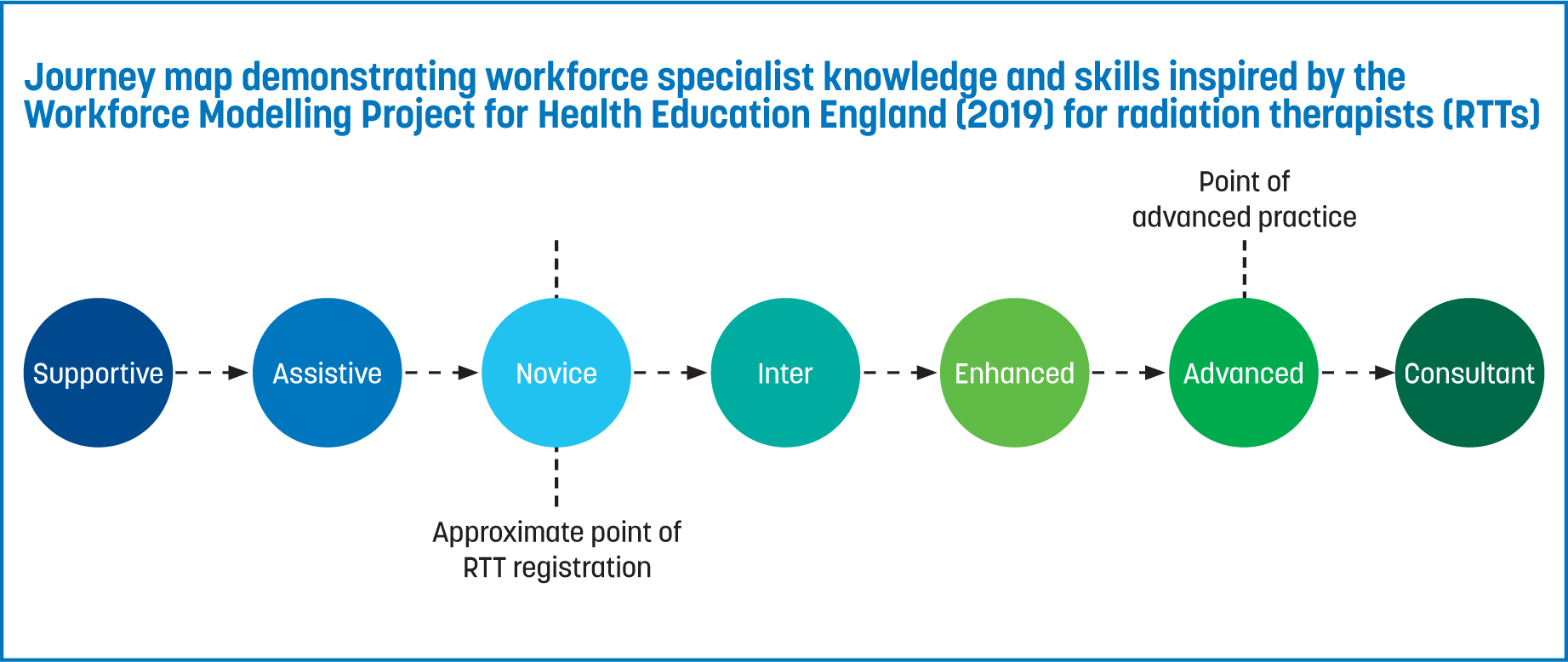

With the emergence of APRT roles in Singapore, a paradigm shift in service user perception may occur, favouring increased acceptance of RTTs in progressive roles rather than a traditional preference for doctor-led care. Although this bears no direct implications for policy, it suggests a potential correlation with the practical implementation of APRT roles, contingent upon legislative changes supporting APRT (Figure 3).

Specific terminology extracted from the literature was structured into tabular format for presentation in Tables 2–4. The language was also interpreted to portray varying levels of risk or readiness. For instance, terms indicating a low risk level included words such as ‘well-established’, ‘efficient’ and ‘smooth integration’. Moderate risk terms suggested some challenges but not critically problematic, such as ‘varying public awareness’, ‘developing’ and ‘moderate challenges’. High-risk terms implied significant challenges, including phrases such as ‘strong influence’ and ‘crucial role’. The visual and tabulated categorisation provide insights into risk representation. The Singapore Society of Radiographers' AP working party can use these insights to advocate for policy change with the Ministry of Health and AHPC.

Professional indemnity

While, in the UK, the HCPC bears the legal responsibility of overseeing radiographers' conduct and performance—which encompasses facets such as educational qualifications, competence and ongoing professional development (HCPC, 2023)—NHSE's rigorous workforce guidelines further augment eligibility criteria for professional bodies to provide indemnity insurance. This form of insurance functions as a protective barrier for practitioners against legal claims arising from their professional practice and is routinely integrated into their membership benefits with the professional body (SCoR, 2020). Moreover, medical malpractice insurance, a variant of private insurance tailored to the specific needs of healthcare practitioners, provides safeguards against legal claims associated with their professional practice. It is imperative to acknowledge that in instances where a healthcare practitioner is acting within the scope of their employment, vicarious liability may be applicable under the Equality Act (2010), potentially holding their employer responsible for any negligence or misconduct (Giliker, 2010).

As the profession's regulator, the HCPC mandated professional indemnity cover for each registrant practicing in 2014 (HCPC, 2014). This measure aimed at safeguarding patients, practitioners and services alike. In the Singaporean context, the Singapore Society of Radiographers does not provide indemnity insurance to RTTs, necessitating practitioners to depend on their hospital establishments for coverage (Allied World Insurance, 2023).

However, this arrangement imposes limitations on the extent of coverage, hindering its comprehensive extension across healthcare settings and professional activities on a national scale.

Healthcare partnerships

When examining the approaches taken by other healthcare system, an inter-system perspective can help emphasise the potential advantages of institutional healthcare partnerships, notably showcased through the concept of twinning. This method, as posited by Kelly et al (2015), envisages the exchange of knowledge, expertise and resources between healthcare institutions from diverse regions, fostering a mutual learning process and bolstering advancements in healthcare delivery, education and infrastructural development. Cadée et al (2016) highlighted four pivotal attributes intrinsic to healthcare twinning. Among these, ‘reciprocity’ emerged as the most frequently cited attribute, complemented by job satisfaction, retention, the development of personal relationships, the dynamic nature of the collaborative process, and the participation of two distinct organisations across diverse cultural landscapes. The literature supports the notion that these attributes can significantly empower healthcare professionals involved in transformative healthcare or system change initiatives (Herrick et al, 2021; Sors et al, 2022).

Within the context of this discourse, an intriguing prospect emerges for potential collaboration between Singapore's health clusters and a well-established healthcare region within the UK. Such collaboration could viably leverage practical insights and lessons from a selected UK region. This consideration encompasses factors such as population size, comparability of hospital resources, the number of health professionals and the intricacies of radiotherapy practice. This is especially pertinent for the effective implementation of APRT role infrastructure, ensuring the presence of relevant governance structures.

By harnessing experiential knowledge derived from an elected UK region, a bespoke framework tailored to Singapore's unique healthcare landscape could be envisaged. This framework, poised to provide a nuanced and context-specific approach, could substantiate region-specific recommendations to Singapore's health ministry. Through doing so, it could serve as a persuasive case for achieving legal coherence and the efficacious implementation of transformative healthcare strategies.

Limitations and recommendations

In advancing APRT in Singapore, a comprehensive approach that addresses both strategic limitations and scopes for future research is required. The disparity in data scope and availability between Singapore and the UK was a significant limitation to this study, as it necessitated the acquisition of comparable longitudinal data to comprehensively assess the effectiveness of the implementation of an APRT role.

National consultations involving experts from Singapore's health clusters—NUHS, SingHealth and NHG—are imperative. These consultations will drive APRT discussions forward, ensuring alignment with the ministry's healthcare strategies. Furthermore, aligning the APRT working group, in collaboration with the UK, may prove effective for developing governance frameworks that support Singapore's AP ambitions.

The official acknowledgment and approval of expanded APRT practices by professional organisations are essential. This is especially significant for Singaporean practitioners adopting the UK's education and training framework, as they might consider seeking recognition and endorsement from the UK's professional bodies. Such recognition could, in turn, offer assurance regarding the necessity for interim policy changes by Singapore's Ministry of Health, and facilitate policy changes. This is a key step in integrating APRT roles effectively.

In future research, the essential task is to establish a Singapore-based CPD education and training framework. Drawing inspiration from the successful UK model, this framework should concentrate on validating practitioner expertise and skills through an accreditation system. Additionally, exploring healthcare partnerships and twinning with the UK, particularly in oncology, can bring mutual benefits. These partnerships can leverage the similarities in infrastructure to enhance the quality of services (Plamondon et al, 2021).

Conducting rigorous longitudinal studies is essential to understanding the long-term consequences of APRT role implementations. These studies should focus on healthcare outcomes, efficiency and patient satisfaction, providing insights into the effectiveness of these roles.

By addressing these strategic measures and focusing on the identified areas for future research, Singapore can effectively formalise APRT roles into its healthcare system. Drawing inspiration from the UK model and fostering international collaboration will ensure improved patient-centric services.

Conclusions

In this conclusion, the authors highlight and reassert the significance of NUHS's initiative to harness global insights for enhancing Singapore's APRT infrastructure. The IAEA-funded scientific visit was pivotal, and provided a template for knowledge, skill and practice guidelines that could be tailored to Singapore's healthcare context. This international learning was not only instrumental in shaping Singapore's evolving AP landscape, but also acted as a catalyst for local authorities to re-evaluate and establish regulations regarding APRT autonomy, including the implementation of an effective indemnity protection charter.

Addressing inherent challenges, such as cultural differences and hesitancy to change within the healthcare system, requires a nuanced and targeted approach. By leveraging lessons from global best practices, Singapore can navigate these challenges more effectively.

Furthermore, the learnings from this initiative hold potential benefits for other nations facing similar challenges in their healthcare professions. The collaborative model serves as a blueprint to overcome professional, legal and governance barriers, thereby fostering the advancement of healthcare policies globally. This conclusion aims to not only summarise the current progress but also to project a forward-looking perspective on the role and impact of APRT in Singapore's healthcare system, highlighting its potential as a benchmark for wider healthcare advancements.