The consultant-level practice is not a recent development; in fact, the UK Labour government first proposed the nurse consultant role in 1998. This was driven by the intent to counter the departure of highly skilled and expert nurses from clinical practice, seeking enhanced earnings and career progression opportunities elsewhere (Department of Health, 1999a). The role was envisioned as a crucial element in nurturing professional leadership, particularly in the broader context of strategically planning high-quality healthcare services for the future. This announcement was followed by the proposal to introduce consultant therapists from allied health professions (AHPs) in 2000, to ensure that their contributions to high-quality patient care was recognised, valued and supported while implementing NHS reforms (Department of Health, 2000).

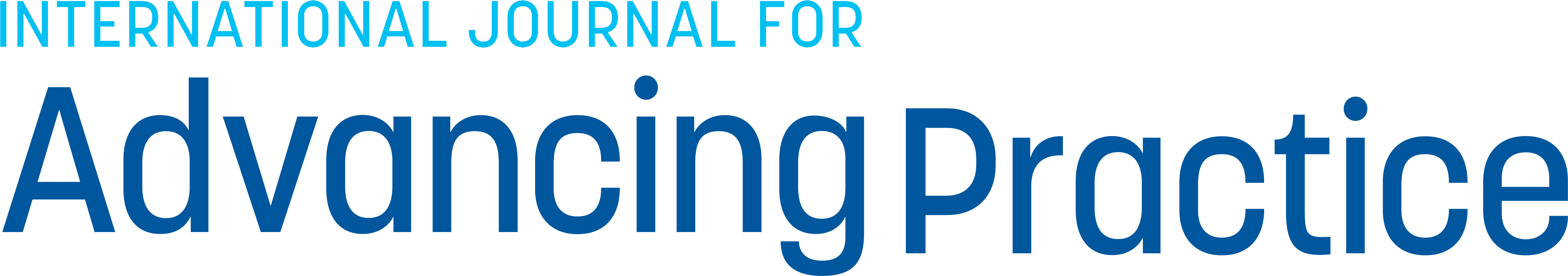

Regardless of the field of professional practice, setting or service, each consultant practitioner post was structured around core functions, serving as a framework that would exemplify the role―expert practice, professional leadership and consultancy, education, and research and evaluation. The core functions of the consultant nurse role were defined through extensive consultation during the creation of a new nursing, midwifery and health visiting strategy. This strategy was documented in the report ‘making a difference: strengthening the nursing, midwifery and health visiting contribution to health and healthcare’ published by the Department of Health (1999b).

One pivotal influence on operationalising the consultant nurse role was an action research project led by Kim Manley from 1992–1994 at one of the new nursing development units (Manley, 1997). Although at the time Manley was not the only consultant nurse in the post, she was the first to research the role and her work provided a preliminary framework that was further modified (Manley, 2002). For research, the consultant nurse role was loosely based on Hamric's model developed for the clinical nurse specialist role in the US, which identified the four sub-roles of expert practitioner, educator, researcher and consultant (cited by Manley, 1997). However, Manley's findings highlighted the necessity of integrating these sub-roles with additional skills and processes.

Being a strategist and visionary, she emphasised the importance of transformational leadership and acting as a change agent, facilitator and role model. Manley also identified essential contextual prerequisites, such as shared values and beliefs and an open, non-hierarchical management structure. These elements were crucial for demonstrating quality patient services, empowering staff, advancing nursing practice and fostering a transformational culture (Manley, 1997).

Over the last 20 years, clinical development and related research across various professions have identified the core interdependent capabilities essential for multi-professional consultant level practice (Crouch and Manley, 2020). These capabilities have been distilled into a robust framework through a co-creation process involving consultant practitioners, aspiring consultant practitioners, professional organisations and related workforce stakeholders across the UK (Manley et al, 2019). Health Education England (2023) introduced the multi-professional consultant-level practice (MPCP) capability and impact framework through the Centre for Advancing Practice.

Figure 1 illustrates the four domains of Health Education England and how consultancy practice across systems is linked to purpose. This framework, while retaining the foundational principles described in 1998, introduces certain nuanced variations that align more closely with the contemporary terminology of today's NHS and key national priorities for the NHS multi-professional workforce. The Centre for Advancing Practice has been instrumental in contributing to the NHS Workforce Plan (NHS England, 2023), recognising consultant-level practice—a step beyond advanced practice—as essential for system transformation and NHS reform (Crouch et al, 2024).

The framework continues to emphasise the integral aspects of expert practice, strategic leadership, system-wide learning and development, research and innovation. However, a key change is evident with an emphasis on navigating and influencing care delivery at various levels, from individual patient interactions (micro) to larger healthcare organisations or systems (meso and macro).

In healthcare delivery, the meso level serves as the bridge between macro-strategic intent and micro-level actions. It focuses on translating strategic goals into actionable plans within organisations, ensuring effective coordination and integration among multidisciplinary teams. This is achieved through consultancy approaches that maximise impact on practice, services, communities and populations. The MPCP framework also highlights values-based practice, emphasising the importance of compassion, respect, person-centred care, safe, evidence-based and integrated services, as well as relationships that challenge stigma and promote inclusivity and collaboration. There is also the expectation that this role offers additionality to workforce capacity and capability. Clearly defining consultant-level practice enables an understanding of its expected impact within each of the key domains.

While it is difficult to determine the exact number of consultant practitioner posts currently active in the UK, their presence is growing, as evident in the authors' organisation where 12 consultant practitioner posts now exist to support the delivery of high quality, person-centred community services across Wiltshire. The latest NHS Long Term Workforce plan proposes increasing the advanced practice pathways over the next 10 years to include more consultant practitioner posts to enable the delivery of better patient care and develop senior decision makers (NHS England, 2023).

Across the UK, there are some variations in the frameworks for consultant level practice in the devolved nations of Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland. Health Education and Improvement Wales (2023) have produced their own framework and NHS Education for Scotland (2025) has updated their framework to include consultant level practice for nurses, midwives and AHPs. The Northern Ireland Practice and Education Council for Nursing and Midwifery (2018) created professional guidance for the core competencies of consultant nurse and midwife roles, co-produced with the Department of Health (Northern Ireland). However, it is not clear if there is a similar framework for AHPs.

The consultant practice self-assessment tool (Health Education England, 2023) offers more formal pathways to facilitate the transition for the most experienced and skilled clinicians from advanced to consultant practitioner roles. It aims to enable practitioners to evidence and align their practice as it relates to each domain, dividing development within consultant practice into stages of expected practice. For example, advanced practice is categorised into 1–3 years, followed by 3–5 years in the consultant practitioner role.

The self-assessment tool allows the consultant practitioner to build a professional portfolio of evidence that represents the impact of their role. This is important for the quality assurance process and is critical at the expert and senior level of practice. It also enables employers, perhaps new to this level of practice, to understand how these roles fit within services and across the integrated care system.

The flexibility within this self-assessment tool acknowledges the individuality, diversity and specificity of consultant practice, as well as the unique priorities of a service, rather than adhering to a one-size-fits-all model (Health Education England, 2023). This self-assessment tool is also useful for revalidation and the appraisal process, ensuring that services can continue to support this senior level of practice through the provision of evidence.

Since the introduction of the MPCP framework, further research is required to evaluate the impact of the consultant practitioner role on both health services and health outcomes. Published case studies demonstrate their impact across the UK and are powerful in presenting a case for further investment and expansion of the role (Manley et al, 2022). The case studies illustrate how the consultant practice role provides the necessary skills and expertise to tackle the challenges and current policy landscape in the UK, ensuring that health and care needs are met using a person-centred approach (Manley et al, 2022). The next section discusses the experiences of three consultant practitioners in Wiltshire, England.

Heart failure nurse consultant practitioner

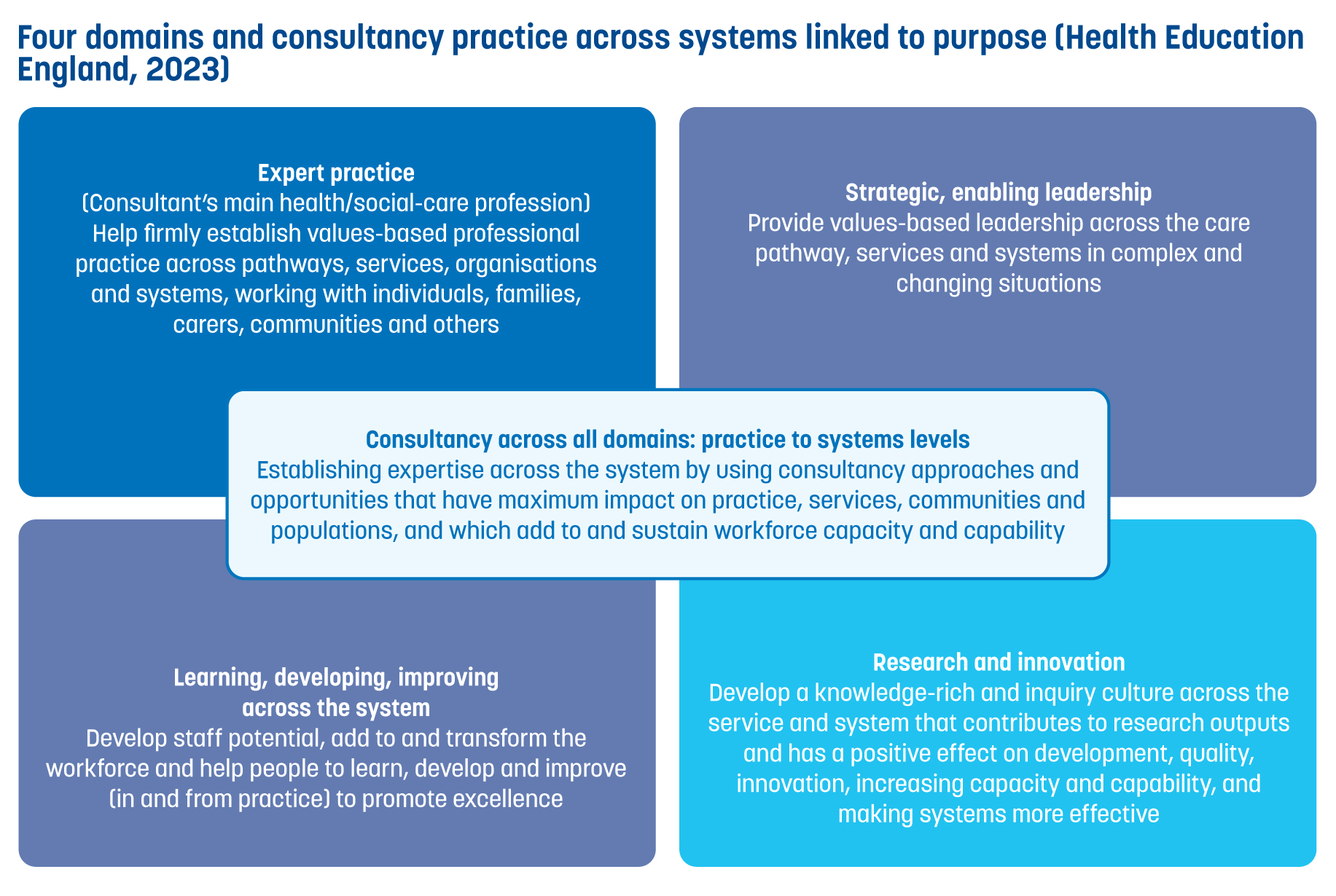

As I reflect on my development into a consultant practitioner, I notice that the three main components (experience, continued professional development and involvement in national heart failure activities) have overlapped to create the practitioner I am today (Figure 2).

Clinical experience

After qualifying as a nurse, I started working in cardiology and never looked back. Within the speciality, I gained experience in a variety of care settings from ward-based care to cardiac catheter laboratories, to a high dependency cardiothoracic unit and outpatient setting. Working as a research nurse developed my interest in heart failure in particular, which led to a heart failure specialist nurse role and ultimately, my current role. Heart failure care is constantly evolving with more research and evidence for providing care to this diverse patient group.

The chronic nature of this disease is such that healthcare professionals have the opportunity to support patients and their families from diagnosis to end-of-life care. There are approximately one million people living with heart failure in the UK and the cost to the NHS is estimated at £2.3 billion (British Heart Foundation, 2023). Therefore, working at a system and national level, my role in advocating evidence-based prognostically beneficial therapies is crucial.

Education in advanced practice

I have had the opportunity to undertake a Master's degree through the Open University, and with support from my employer, have progressed through a number of advanced clinical skills modules. This higher-level learning supplemented my clinical practice and enabled me to develop into advanced roles within my specialism. As a result, I was able to secure the Health Education England advanced practice digital badge after successfully submitting the e-portfolio.

The Wiltshire community heart failure service was a new facility at the time of my joining, which enabled me to create a provision of care best-suited the patients in the community and at a variety of clinic sites, reducing the distances patients had to travel for specialist reviews. A nurse-led rapid access heart failure clinic in the community enabled diagnostic tests and clinical review on the same day, improving timelines from referral to diagnosis and the implementation of a management plan. While complex cases are supported by discussion with local cardiologists, the implementation of evidenced-based management plans based on advanced assessment are provided by myself and the team.

Involvement in national activities

Involvement in activities with national cardiology societies, such as the British Society for Heart Failure and the British Cardiovascular Society, has given me insight into national strategies for promoting high quality and evidenced-based heart failure care. Networking with colleagues and having peer support has enabled me to develop an increased regional and national presence, with opportunities for academic writing and involvement in webinars and conferences. I am currently developing a regional heart failure nurse working group to integrate care and improve patient pathways across the integrated care system.

Impact of the role in heart failure services

Consultant Nurse, Hospital at Home

Professional curiosity, community health and clinical leadership are all key areas that have been crucial to my development and career journey into consultant practice.

Professional curiosity

I have always been inquisitive, whether engaging with those on my caseload, colleagues, education supervisors or mentors. I actively listen to understand issues, decisions, feedback and learning, all of which contribute to my growth mindset. Asking questions not only strengthens my critical thinking, it also challenges assumptions, explores alternatives and deepens my understanding of complex problems.

This practice of inquiry and active listening reflects my commitment to personal and professional growth, effective communication and continuous learning—qualities that are essential to my career. I continue to cultivate this mindset in my new role as a consultant practitioner, collaborating with like-minded colleagues and critical companions as we develop the hospital at home service in Wiltshire.

Community nursing

Since qualifying in 1994, I have spent much of my career in the community so I can nurture my passion for personalised care planning and providing older people with expert and complex nursing care at home. I find working in the community fascinating. The opportunities for working in a multi-professional team are maximised in the community and learning is optimised as I work alongside experts in their professions and recognise the importance of access to a specialist in the community. As I lean into the key domains of consultant practice, I realise, now more than ever, that research and innovation is critical to how we deliver sustainable services that provide better outcomes and better care.

Attending regional research networks, shadowing opportunities with nursing leaders, sharing best practice through communities of practice and the future NHS platform has really opened my eyes to the importance of research culture. Joining the community nurse consultant network and my organisation's research strategy group has also helped me appreciate this and develop my confidence as a research champion promoting research activities. I now focus on sharing this message, encouraging others to consider their research activities and to change the language, breaking down barriers to developing a research culture.

Leadership

My understanding of leadership has developed over my career and I am grateful for all the experiences I have had, both in clinical practice as well as formal education and training. Taking opportunities to work alongside, listen to or network with senior leaders has been a priority throughout my career. Reflecting on the practices of my role models and understanding why they have made an impact on my practice and which attributes resonated with me, has helped my understanding of leadership qualities. The NHS Leadership Academy (2025) is an excellent central hub with many resources such as the clinical leadership competency framework launched in 2010 and the healthcare leadership model in 2015. Using this framework and model has been key to understanding the dimensions for developing my leadership competence and capacity. The 360-degree feedback assessment is an excellent tool designed to give insight into other people's perception of your leadership abilities and behaviour. My 360 feedback highlighted my strengths, but perhaps more importantly, my blind spots and identified opportunities for development and growth. While it is easy to get lost in the different types of leadership defined in the literature such as systems leadership, inclusive leadership and compassionate leadership, focusing on the nine dimensions within the model is helpful for developing a dynamic approach that changes depending on the situation you are presented with. Followship is also important and critical for learning from colleagues, knowing when to lead from behind and see others flourish. We can all develop leadership qualities and attributes, but understanding and knowing ‘self’ feeds authenticity as a leader and has been crucial in my leadership journey.

Impact of the role in hospital at home services

Within the hospital at home services, the consultant practitioner role is the golden thread that transcends the micro, meso and macro levels of the healthcare system.

Consultant practitioner (rehabilitation and frailty), physiotherapist

My career thus far reflects a ‘squiggly career’ (Tupper and Ellis, 2020) in healthcare. Since qualifying, I have had roles both in the NHS and the private sector, as well as continued roles in national societies and forums. This has exposed me to various working landscapes, governance structures and patient cohorts, challenging me to adapt and develop my skills for the individuals in my care and the team around me. I believe these opportunities have particularly supported me in the areas discussed below.

Advocacy in leadership

A consultant practitioner role typically represents the senior non-medical clinician in the room, and this often means I represent the wider AHP professions. In order to develop leadership, I have learnt through experience to balance advocacy for AHP professionals with organisational priorities and strategy.

To advocate for other professions, I have worked closely with colleagues and actively participate in their day-to-day roles to allow a true understanding of how they support patients and the wider organisation in service delivery. Leadership in a consultant practitioner role has to be an active leadership style, whether this is encouraging others to take opportunities while being available for support, advocating for the need for an AHP voice in the room, or creating opportunities for others.

Helicopter view and ground level involvement

One of the key benefits, and what I most enjoy about the consultant practitioner role, is that it allows the dual scope of a helicopter view and ground level involvement in service delivery. This can be challenging because you need to be actively involved in complex clinical delivery for individuals, in addition to being able to step back and see the bigger picture of the overall service delivery and strategy.

Being able to do this means being able to separate yourself from individual clinical issues and to identify themes and trends in clinical pathways. In reality, this dual view allows the ability to positively impact services in real time and create change by doing; this also allows for a true co-productive nature to service improvement as consultant practitioners have a vital role in implementing the change, not just planning and overseeing improvements.

First, seek to understand then be understood; I first read the 7 Habits of Highly Effective People by Stephen Covey (Covey, 1989) a couple of years into my career and this particular quote has resonated with me ever since. In my earlier career, this was a mantra to help individual clinical practice; it reminded me to listen to patients, to explore what matters to them and to ensure that we were having a collaborative discussion.

As my role developed, I have learnt that this does not apply just to individual conversations and interactions but also to service level issues, system-wide strategy and national agendas. In consultant practice, you are often a key decision-maker, representing multiple professions, teams or services. Therefore, it is imperative that you take the time to listen to stakeholders (patients, colleagues etc), review pertinent data and truly understand the nature of the issue or information before forming an opinion and decision. This is the first part, ‘first seek to understand’. The second part is about developing the ability to relay your opinion, decision, proposal (whether an individual treatment recommendation or a national guideline decision) into an information style that is understandable to the audience. This could be a data set and presentation at a national forum, a drawing for a patient, a metaphor for treatment or a full academic journal article. Without this, the time and effort taken to understand the problem will be lost in translation and the outcome of the given intervention will lose effectiveness; we must understand our audience to support them.

Impact of the role within community therapy services

Box 1 provides tips for successfully developing into a consultant practitioner.

Conclusions

The article discusses consultant level practice and its evolution through time, now firmly underpinned by an evidenced-based framework with the aim of increasing understanding about the role and to offer some real-world experiences through reflections from three consultant practitioners. This insight into their professional career paths, and the key influences that have shaped their journey so far, demonstrates the dynamic nature of the role and reflects the changing NHS in the UK and the need to develop consultant level practice beyond advanced level practice. The common themes of expert specialist practice—building your network, developing relationships across traditional boundaries, leadership at all levels, education and research—are evident in these reflections. So is the need to develop the capability and impact at micro, meso and macro levels to implement system-wide improvements that reflect values-based practice. This knowledge and understanding of the role for developing the NHS consultant practice workforce is useful for integrated care boards, NHS managers and service leads, as well as aspiring consultant practitioners.

TIPS FOR SUCCESSFULLY DEVELOPING INTO A CONSULTANT PRACTITIONER

Workforce reform is needed now more than ever with the challenges faced by health and social care in the UK. The multi-professional consultant practitioner role can support the challenges faced and influence sustainable change and quality improvements to meet the needs of the populations they serve.