Political and societal changes have seen increased numbers of professionals becoming nurse independent prescribers (NIPs) (Weiss, 2021). The NHS Long Term Plan (NHS England, 2019) identified that breaking down barriers and pooling resources will facilitate continuous improvement, assist in achieving government targets and, most importantly, enhance patients' access to medicines.

Disparities across services have already been identified, with workforce deficits and increased numbers of patients living with long-term conditions impacting the delivery of primary care services (Edwards et al, 2022). Increasing patient demand and the decline of the GP workforce is delaying patients' access to medication. This issue could, in part, be alleviated by UK-based NIPs, who could support patients through providing earlier access to medication, especially for those receiving end-of-life care (Campling et al, 2022).

NIPs are professionals that have successfully completed the V300 prescribing module at an accredited university and work within the competency framework for prescribers (Royal Pharmaceutical Society, 2021). They have the skills and knowledge to prescribe any medication within their area of expertise in practice; this is inclusive of medicines in the British National Formulary (BNF), controlled drugs in schedules 2–5 and unlicensed medicines (Nursing and Midwifery Council, 2022). This allows NIPs to prescribe at an autonomous level, which is equivalent to that of a doctor; however, the prescription area must be within their scope of clinical practice (Weiss, 2021).

NIPs are a growing workforce. While there are approximately 58 000 professionals possessing the qualification in the UK, it is currently unknown how many are using their advanced skills (Cope et al, 2016).

Not only does NIP provide nurses with advanced skills, but it has also been identified that it improves patient care by providing patients earlier access to medication, which is crucial for symptom control within palliative care (Edwards et al, 2022). It can also prevent unplanned admissions into the acute hospital trust (Latter et al, 2020).

Patients experiencing a life-limiting condition should be receiving a responsive service for the assessment of symptoms, the delivery of which can often be complex. A timely response can provide effective symptom control and improve both palliative and end-of-life care (Latham and Nyatanga, 2018). NIPs, due to their speed, efficiency and influence, can aid in the delivery of medication across palliative care (Latter et al, 2020).

Aim

The overall objective of this survey was to explore the experiences of NIPs working across both primary and secondary palliative care settings. The author sought to:

- Understand the frequency of individual NIPs prescribing practice

- Evaluate and gain a clearer understanding of the experiences of NIPs within the organisation's community palliative care team, the inpatient unit within the hospice and the local acute trust's palliative care team

- Record opinions and experiences, to explore the context of the NIPs prescribing practice and assist in the identification of barriers and facilitators

- Identify whether prescribing is beneficial to patients and NIPs

- Explore the medications prescribed and the frequency of prescribing

- Provide recommendations for organisations

Method

Validity

Data were collected via mixed-methodology survey, which sought to identify the facts, attitudes, knowledge, expectations, experiences and opinions of NIPs (Parahoo, 2014). To demonstrate ethical governance, the questionnaire was piloted with a small number of hospice-based NIPs and one member of staff from the research and education department (n=3) (Moule and Goodman, 2009). Prior to the final version being published, the questionnaire was slightly adapted in response to feedback received.

Design

An online survey using the web-based platform Qualtrics (2022) was designed. The survey was informed by the findings from a literature review that was completed as part of the service evaluation review of NIPs within the organisation. The survey used both open, closed, multiple choice and free text questions, which allowed the respondents to share their experiences and opinions (Hindi et al, 2019).

The survey was structured into four sections. The first section gathered information regarding the participants, including their time working in palliative care and the clinical area they prescribe in.

The second section collected information regarding if they had ever experienced feeling pressured to prescribe medications outside of their scope of practice. The third section identified what medications they were prescribing, as well as the challenges and benefits to the patients and NIPs. The final part identified what support is needed pre- and post-qualification, barriers to prescribing and if the organisation should continue to fund NIPs.

Recruitment of participants

Purposive sampling was used to select the participants. This approach assisted with obtaining detailed experiences of NIPs, who were knowledgeable and experienced in the delivery of medications (Moule and Goodman, 2009). The project was designed for NIPs working in palliative care within the hospice, their community trust and the local acute trust's palliative care teams. The survey comprised of 13 questions, which were sent to nine NIPs. They were distributed by means of email, directly from Qualtrics.

Data collection

Data collection for the online survey took place over a 7-week period, which commenced on 14 October 2022. Two email reminders were sent to participants on weeks 3 and 6. The participant's answers and opinions were anonymised by Qualtrics.

Ethical approval

It was established via the Health Research Authority (2022) decision criteria that ethical approval was not required.

Data analysis

Quantitative data were obtained directly from the results within the Qualtrics (2022) platform; this automatically produced the quantifiable results. Qualitative data were analysed thematically to identify common reoccurring themes; this data was necessary to gain a more in-depth insight into experiences that occurred within a less-formal structure (Moule and Goodman, 2009; Ellis, 2019). The qualitative data did not identify the participants.

Results

A total of six responses from the survey distribution were received. There was a variation in the length of time the participants had worked as registered nurses within palliative care; it was requested for the participants to include the time spent working within palliative care in their previous roles. Responses ranged from 1–30 years. This did not include the amount of time they had been registered as an NIP.

Daily prescribing was undertaken by two NIPs (28.57%), 2–3 times per week by two NIPs (28.57%), once weekly by one NIP (14.29%), once monthly by one NIP (14.29%) and one NIP recorded (14.29%) never prescribing. Of the 6 participants (100%), all of the NIPs did not feel pressured to prescribe any medications that were out of their scope of practice.

Settings where prescribing was undertaken

NIPs responded that they prescribed in a variety of settings (Table 1). Most of the prescribing took place in the patients' homes; few NIPs mentioned prescribing in clinic settings and the inpatient unit. It must be acknowledged that NIPs who are using their skills in the community will be prescribing in different settings, which include patients' homes, clinics, residential and nursing homes.

Table 1. Settings of Prescribing

| Setting of prescribing | Frequency of nurse independent prescribers |

|---|---|

| In patient unit | 1 |

| Hospital | 1 |

| Patients' homes | 4 |

| Nursing homes | 2 |

| Residential homes | 2 |

| Clinic setting | 1 |

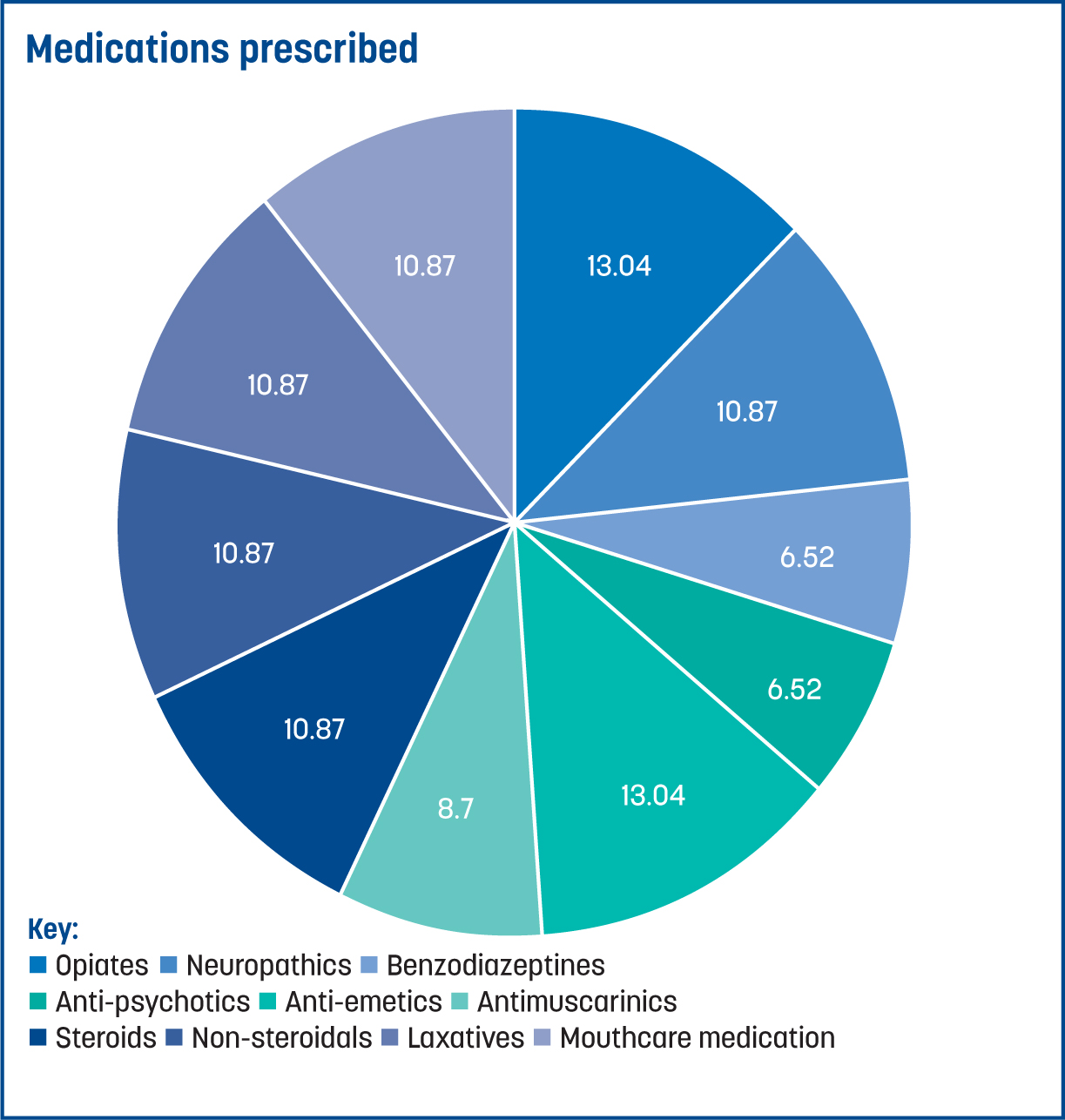

Medications prescribed

Figure 1 depicts the types of drugs that were prescribed. It highlights that while the most common prescribed drugs were opiates and anti-emetics, a wide range of medications had been prescribed by NIPs:

- Opiates (13.4%)

- Anti-emetics (13.04%)

- Neuropathic medication (10.87%)

- Non-steroidal medication (10.87%)

- Steroids (10.87%)

- Laxatives (10.87%)

- Mouth-care medication (10.87%)

- Anti-muscarinic medication (8.70%)

- Benzodiazepines (6.52%)

- Anti-psychotics (4.35%).

These medications were selected as they are the most used groups of medications prescribed under the guidance of the local formulary; many were prescribed ‘off label’ (Wessex Palliative Physicians, 2019).

Experiences of the challenges within practice

Challenges and themes encountered by NIPs were described as:

- The lack of access to electronic prescribing: participants detailed how electronic prescribing would save time and leave a clearer trail of evidence. Handwriting on prescriptions was described as complicated and carrying an element of risk. Some mentioned that it was quicker to ask GPs than write out prescriptions by hand and give to the patient. NIPs who had access to electronic prescribing found this a difficult system to navigate, but beneficial for safer prescribing

- The need for supervision and the opportunity to discuss prescribing with their mentor.

Is prescribing beneficial to clinical practice?

Themes developed from the participants (n=6) were as follows:

- Increased pharmacological knowledge has enhanced clinical practice and is believed to make NIPs practice safer, which has improved confidence

- Medications can be accessed quicker, therefore improving symptom control; it also saves doctors' time

- Within the patient's home, changing prescribing charts aids in better symptom control.

Do you think that prescribing is beneficial to patients and should the organisation support this?

Themes developed from the participants (n=6) were as follows:

- Medications can be commenced earlier

- Patients are more informed of the medications they are taking. This also helps the patients to understand what is happening, as they have trust in the prescribers due to having a professional relationship with the NIP

- All of the participants (100%) agreed that NIPs should continue to be supported and funded by the organisation.

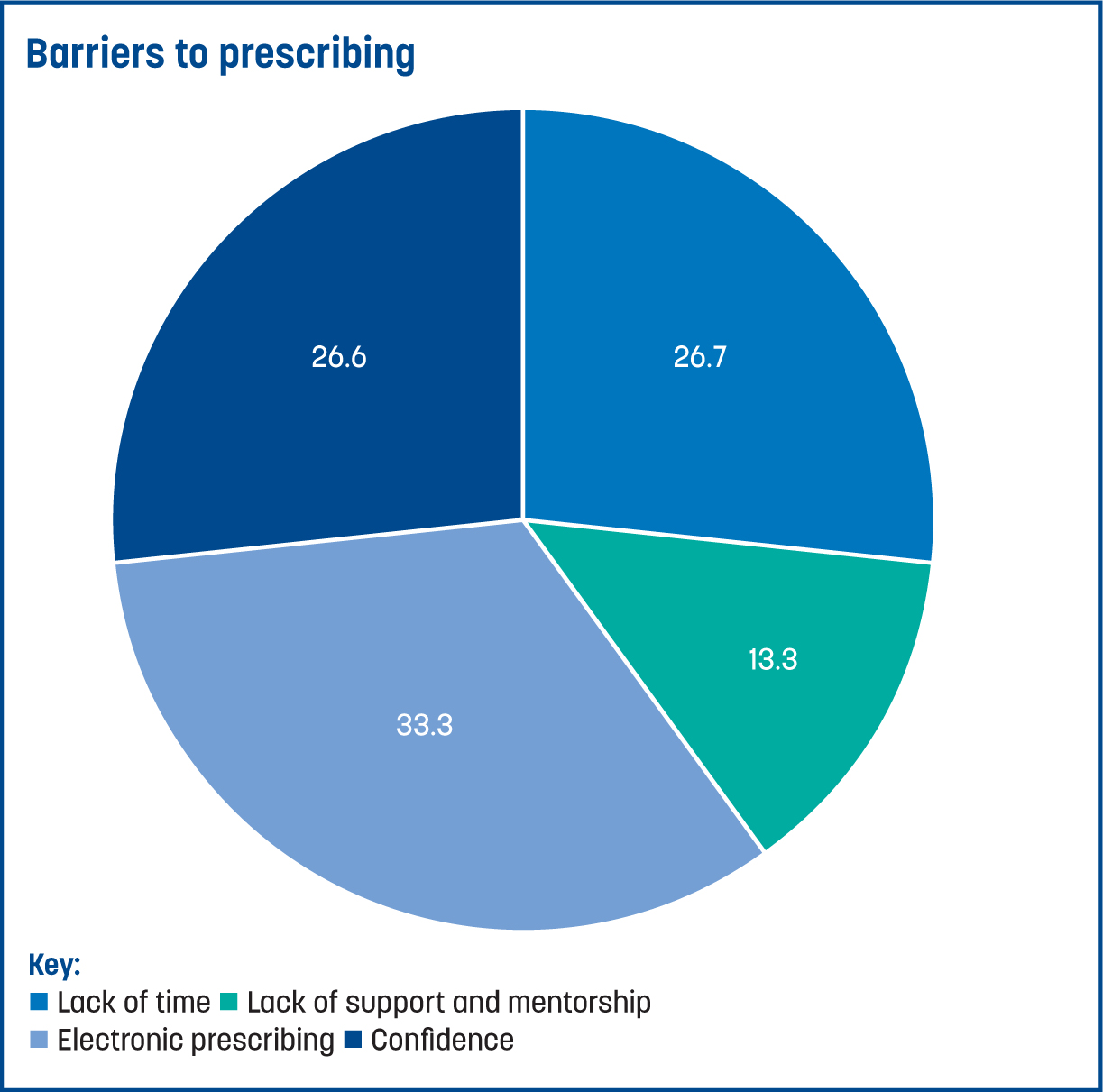

What do you think are the barriers to prescribing?

Figure 2 displays the responses to the multiple-choice questions. The highest recorded barrier to prescribing was the lack of electronic prescribing (n=6; 37.5%).

Equally, 27% of NIPs said that lack of time and confidence affected their capacity to prescribe, with 13% feeling they had a lack of mentorship and support.

How do you maintain your competency?

Results showed that competencies are maintained by mentor/peer support (29.17%), reflective practice (29.17%), multidisciplinary team meetings (25%) and yearly updates 16.67%.

Discussion

Cope et al (2016) acknowledge that experience is essential for the effective integration of NIPs, as it gives the confidence to prescribe within their scope of practice and work within their boundaries. Each participant in this study had experience of working within palliative care, ranging from 1–30 years. This was across both the roles that they had previously been employed in and within the organisation. As this study was limited in size, it may have been beneficial to ascertain how long each NIP had been qualified for, and whether this enhanced their confidence within their prescribing practice for diagnostic and clinical decision-making.

The results demonstrate that there is a variety between how much NIPs prescribe; one NIP reported having never prescribed, while another reported prescribing daily. There were several barriers as to why the NIPs were reluctant to prescribe, such as a lack of electronic prescribing, time, confidence and support from others. It is still unclear why some NIPs lacked the confidence to prescribe; this could be explored further by using focus groups to generate discussions and further consider where support should be directed (Ellis, 2019). It is interesting to note that while not all the participating NIPs frequently prescribed, all of them agreed that the organisation should continue to fund the training of NIPs, as it achieves a better outcome for patients and their own clinical practice. Arguably, the volume of prescribing carried out may not be a true indicator of how prescribing is used within palliative care. Holding a NIP qualification can help with the increased knowledge with regards to pharmacological decision-making and medicine management, both with patients and professionals (Hall et al, 2019).

The survey confirms that confidence and time are seen by the NIPs as essential to being able to increase their capacity for prescribing practice. The results demonstrate that prescribing is beneficial to the patients and also for clinical practice, but in order to increase prescribing activity, confidence needs to be considered. Previous research has identified that the transition from course completion to applying it to practice does appear to be problematic. It is acknowledged that a lack of confidence, not feeling prepared to prescribe and the fear of making an error can hinder the development of the prescriber (Ziegler et al, 2015).

Confidence can also be affected by the prescribing of unlicensed medications; this is potentially due to the lack of evidence and research in areas such as palliative care (Tatterton, 2017). NIPs can face challenges within their practice; as they are adapting to a new skill, their responsibilities and accountability increases, and they also must integrate these new aspects into their workplace settings (Latham and Nyatanga, 2018).

Increasing confidence for NIPs certainly reinforces the requirement for ongoing support and mentorship. There is a cost implication on the funding provider if NIPs do not proceed to prescribe (Ziegler et al, 2015); therefore, there could be an understandable reluctance to provide training from some organisations. Solutions could be addressed within the organisation to ensure the numbers of NIPs are supported and confident in their practice (Campling et al, 2022). This will not only be beneficial to the patient, but will also reduce the demand on GPs (Weiss, 2021).

The Nursing and Midwifery Council (2022) recommend within their guidance that NIPs receive regular supervision, thus ensuring safe practice. This not only supports prescribing from a governance perspective, but also provides an additional form of peer support, a capacity to highlight any issues or concerns they may have, and also explores further opportunities to improve care provision.

The medications prescribed within palliative care often support symptom control, the most common of which relate to pain and nausea. A lack of confidence around the generally low numbers of medications prescribed could be attributed to the many medications that are used unlicensed and ‘off label’, often with a lack of evidence trail (Tatterton, 2017).

Current evidence supports the results from this survey. Campling et al (2022) state that a lack of access to electronic prescribing can lead to delays in obtaining medication. The NIPs surveyed in this study implied that it was much more efficient for the GPs to prescribe as it was timelier for the patient and also enabled an immediate update of the patient's records. Increasing evidence is showing that professional groups must have access to both shared records and electronic prescribing (Graham-Clarke et al, 2018). This further concurs with the results of this study, which highlighted the importance of electronic prescribing and how it is perceived to be beneficial by NIPs.

Enhancing and supporting the skills of NIPs will also have a positive influence on the service delivery for both patients and carers. The ability to prescribe ensures that patients have timelier access to medications, as well as reduce the pressures placed on both NIPs and doctors.

It must be recognised that this study focused on NIPs within primary and secondary care. It is important to acknowledge that non-medical prescribers (NMPs) are multidisciplinary, with varying professional healthcare backgrounds. It would be valuable to compare this study of NIPs with NMPs within wider healthcare settings.

Limitations

This study was limited was its small sample size, which solely focused on NIPs within the organisation and the palliative care teams within the acute trust. The response rate was not as high as anticipated, even following reminder emails. A further study of a larger sample size including the wider community care teams maybe beneficial for identifying additional experiences and behaviours that could influence change and work development within integrated teams.

Qualtrics did not identify how many respondents answered the questions in regard to experience and views. It may have been beneficial to identify how many of the participants responded to these questions as data could potentially have been missed around experience and views.

Conclusion

This is the first survey that has been undertaken within the organisation to examine the views, individual practices and experiences of prescribers. While the sample size of this study was small, the experiences that have been acquired are similar to that of other studies including, Campling et al (2022) and Edwards et al (2022). Barriers that have been identified through NIPs experiences should be considered and acted upon, to enhance the prescriber's skills and improve service delivery, which will aid in a higher standard of patient care.

It has been established that an understanding of the NIP role is a key component of integration, not only within the clinical teams but also within the wider healthcare setting; trust and confidence are essential for successful prescribing (Hall et al, 2019). In addition, strong clinical leadership needs to be established among NIPs in order to improve integration and performance in the workplace; NIPs need to take responsibility for their own practice, their team and the wider organisation (Kings Fund, 2017).

While many professionals have embedded prescribing into their practice, some organisations continue to see prescribing as a purely medical role (Graham-Clarke et al, 2018); utilising and integrating the role of the NIP is essential to improving the approaches of prescribing across all healthcare areas (Weiss, 2021).

KEY POINTS

- Leadership skills are essential for both the prescriber and their manager to ensure that prescribers are using their skills and providing safe practice

- Formal ongoing mentorship is needed to facilitate and support prescribing

- A yearly questionnaire reviewing prescribing activity would be beneficial for future practice to identify growth in prescribing following the results of this survey.

CPD / Reflective Questions

- Do you think your organisation has the correct support in place? If not, how could you influence this?

- How can you promote prescribing in your workplace for enhanced patient care?

- How could you support your nurse independent prescriber and non-medical prescriber colleagues to increase prescribing practice and gain confidence?

- Identify one area in your prescribing practice that you would like to improve, how can you achieve this?