In the UK, patients with acute general surgical conditions were historically assessed in the emergency departments (EDs). Surgical assessment units (SAUs) were established to reduce the financial pressures and workloads in the ED, while diverting surgical patients to a dedicated and clinically focussed area for timely assessment before hospital admission or ambulatory treatment (White, 2023). SAUs have long been managed by the traditional surgical team, consisting of doctors with different roles (The Royal College of Surgeons of England (RCSeng), 2016).

However, global health systems have been compromised by safe working hour restrictions (Wheeler et al, 2022). In the UK, the European working time directive reduced the average weekly working hours for doctors to 48 hours (British Medical Association, 2024). Similarly, the accreditation council for graduate medical education placed an 80-hour per week restriction in the US (Eaton et al, 2019). These restrictions risked staff shortages, service delivery and patient care (RCSeng, 2016; Eaton et al, 2019; British Medical Association, 2024).

One solution was to retain and develop the existing staff. The NHS Long Term Workforce Plan initiated wider reforms to address the future needs of the organisation (NHS England, 2024). This started the integration of an adaptive and responsive workforce worldwide, using experienced healthcare professionals such as nurses, midwives and allied health professionals (Eaton et al, 2019; Stewart-Lord et al, 2020; Wheeler et al, 2022). The RCSeng (2016) recommended that, to enhance patient care, surgical firms needed to evolve into extended surgical teams (ESTs). ESTs encompass consultants, doctors in training, specialty and specialist doctors, and non-medical practitioners including advanced clinical practitioners (ACPs).

In the UK, ACPs are experienced healthcare professionals from a variety of backgrounds, educated at a Master's level to develop their skills and knowledge within the four pillars of advanced practice: clinical practice, leadership, management and education and research. The extended role was intended to transform and modernise pathways of care, while breaking down traditional professional boundaries (Health Education England, 2017). However, in recent years, ACPs have been used to ‘fill roster gaps’ and ‘plug holes’ in ward cover (RCSeng, 2016). ACPs provide a significant contribution to care of the surgical patient by undertaking duties traditionally performed by doctors at a competency level between foundation to core surgical trainee (RCSeng, 2018).

While the RCSeng have highlighted the potential benefits of having ACPs within the ESTs, there is limited research examining its value, particularly on their contribution to quality standards. Quality standards are identified by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) to improve the quality of care provided within health services. One quality standard outlines the quality statements and measures to reduce the risk of venous thromboembolism (VTE) in people aged 16 years and over, who are in a hospital (NICE, 2021). VTEs, which include both deep-vein thrombosis (DVT) and pulmonary embolus, continue to be a global health burden with serious mortality, morbidity and health economic consequences (McCormack et al, 2020). Worldwide, 1–2 per 1000 adults are diagnosed with VTEs annually (McCormack et al, 2020), with 99 per 100 000 VTE-related deaths within 90 days after discharge from a hospital in the UK (NHS Leicestershire Partnership, 2024). In 2022, the UK recorded one of the highest post-operative DVT rates at 377 per 100 000 hospital discharges, when historically the UK had been one of the lowest on average of countries recording data (Nuffield Trust, 2023).

To ensure a high-quality VTE prevention service, NICE (2021) recommends that all surgical patients should have their risk of VTE assessed using a national tool and commence on VTE prophylaxis as soon as possible. The tool recommended, and used in this study, is the Department of Health (2010) VTE risk assessment tool. It examines the risk of thrombosis and bleeding in relation to patient and admission criteria. A decision regarding prescribing low molecular weight heparin and mechanical prophylaxis can then be made. The national VTE Commissioning for Quality and Innovation (CQUIN) goal is that 95% of all inpatients aged 16 years and over should have their risk of VTE assessed (Nuffield Trust, 2023).

Another quality standard outlines the quality statements and measures regarding identifying acute kidney injury (AKI) in patients admitted to the hospital. AKI continues to be a global burden, particularly in developing countries, resulting in over 13 million diagnoses and 1.7 million deaths annually worldwide (Abebe et al, 2021).

Adults, particularly those aged 65 years and over, who have emergency admissions to a hospital, have significant past medical history and undergo surgery have an increased risk of AKI (NICE, 2023a). AKI results in a 12-day median length of stay and accounts for approximately 100 000 deaths every year in hospitals in the UK (Renal Association, 2020). AKI-related inpatient care costs the NHS in England around £1.2 billion each year (NICE, 2023b).

While there is no nationally proposed AKI risk assessment tool, the completion rate of the locally devised AKI risk assessment tool was examined in this study. The assessment tool scored for age, hypotension, signs of sepsis and hypovolaemia, use of nephrotoxins and comorbidities. A maximum score of 20 can be achieved, with a score of more than four recommending daily blood tests, medication review and fluid status assessment.

Aims

This study evaluated the current service provision within an acute general surgical setting to identify whether the introduction of ACPs within the EST improved national quality standards and patient care.

Methodology

The study used a single-centred quantitative retrospective longitudinal design to describe the relationship between the introduction of ACPs within the EST and its effect on national quality standards. The study was conducted in the SAU of a large teaching hospital between September 2021 and May 2022. ACPs joined the EST in August 2018, when they were enlisted on the core surgical trainee roster. Data were collected for January 2018, before the ACPs joined the EST, and after their introduction in February 2021. The sample population was obtained through convenience sampling.

Any general surgical patient who attended the SAU during January 2018 and February 2021 was recruited. Inclusion and exclusion criteria were then applied to determine the eligibility and patient selection (Table 1). A total of 1399 patients were recruited for the two outcome variables: completion of VTE risk assessment and completion of AKI risk assessment.

| Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria |

|---|---|

| Aged over 17 years | Urological attendance/admission |

| Acute general surgical attendance/admission | Vascular attendance/admission |

| Nursing attendance |

Data collection

Clerical personnel logged all the SAU attendances in an admission book, recording each patient's hospital number and time of attendance. Admission books were used to identify each attendance and to access the electronic patient record system. Secondary data for January 2018 were extracted from the clinical management system iCM, while the data for February 2021 were extracted from Lorenzo.

The data extracted included whether a VTE and AKI risk assessment was completed, the time it was completed in (minutes) and whether the patient was clerked by an ACP or a doctor. The data were recorded on a spreadsheet, one for each outcome variable, with a row for each patient and a column for the corresponding data. Each patient record was represented as a case number to ensure anonymity and confidentiality.

Analysis

To evaluate quality measures the outcome variables ‘completion of VTE risk assessment’ and ‘completion of AKI risk assessment’ aimed to establish whether the risk assessments were completed within 4 hours of attendance to the SAU for January 2018 and February 2021. Therefore, the two variables were dichotomous in nature; the data were divided into one of two categories, yes or no.

Discrete data were obtained by counting the number of cases that achieved a given outcome and then expressed as a percentage of the total number of cases. The descriptive statistics were expressed using cluster columns to demonstrate proportions and visual comparison.

Logistic regression was used to determine the relationship between the completion of VTE and AKI risk assessment and the introduction of ACPs within the EST. The results were represented using odds ratios (ORs). Regression was used to predict the value of one continuous variable from another, if the two variables were associated.

Logistical regression was specifically used to describe the relationship between a dichotomous variable and a known experimental variable. ORs measured the association between the experimental variable and the outcome variable by comparing the odds of the outcome occurring because of exposure and the odds of the outcome occurring in its absence.

To establish whether the mean of the sample accurately described the population from which it was drawn, confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated. A CI of 95% ensured that there was a 95% certainty that the population mean was within two standard errors of the sample mean.

The standard error is the dispersion of a set of means. Therefore, all analyses were presented with a 95% CI and as probability values (P value). Variables in a population are not related, and if the probability of finding a relationship between the variables and a population is 0.05 or less, then this relationship has not occurred by chance. Therefore, p<0.05 was regarded as statistically significant. All analyses were conducted by a statistician using Stata version 16.

Ethical approval

A research ethics review was completed and all personal information and data relating to the study was stored on an encrypted USB device, preventing unauthorised access and corruption. No breach of data protection was identified throughout the course of the study.

Findings

VTE risk assessment

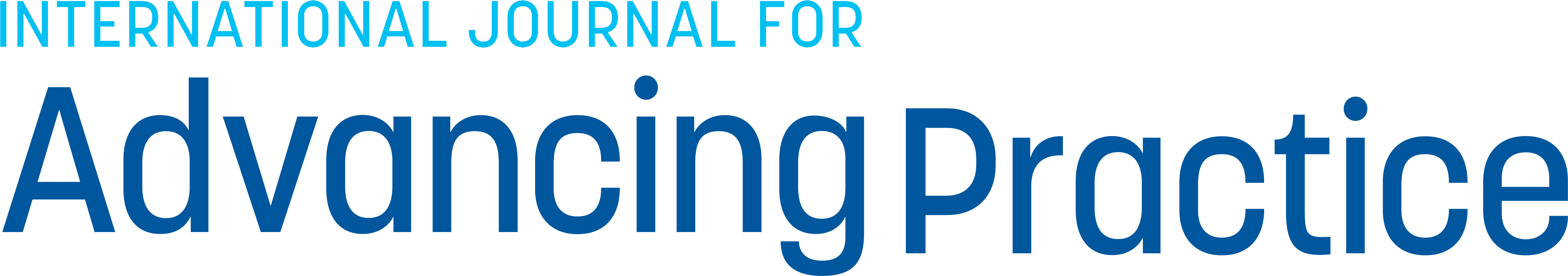

A total of 842 general surgical patients were assessed by the SAU in January 2018, of which 533 patients (63%) had their risk of VTE assessed and of those, 406 (76%) were completed within 4 hours (Figure 1). In comparison, 557 general surgical patients were assessed by the SAU in February 2021, of which 277 patients (50%) had their risk of VTE assessed and 195 (70%) of those were completed within 4 hours (Figure 1).

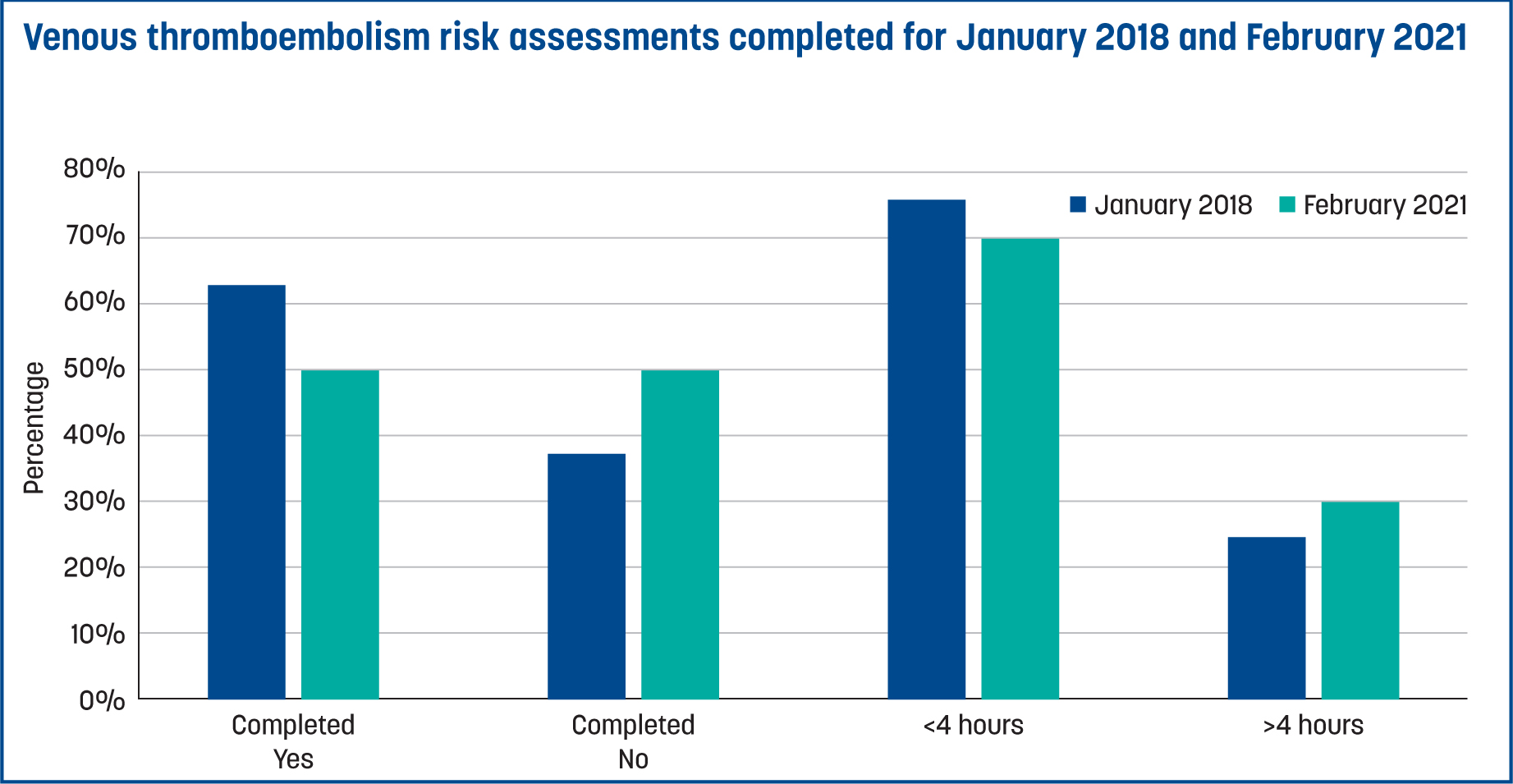

The mean time taken to complete a VTE risk assessment in January 2018 was 324 minutes, as compared to 364 minutes in February 2021. When the patient was clerked by an ACP, 82% of VTE risk assessments were completed and 58% were completed within 4 hours. This compared to 57% of VTE risk assessments completed and 42% within 4 hours when the patient was clerked by a doctor (Figure 2). For patients who went on to be admitted to the hospital, 93% of VTE risk assessments were completed in January 2018, compared to only 85% in February 2021. Of the patients admitted by an ACP, 98% had their risk of VTE completed as compared to 48% of patients admitted by a doctor.

The analysed data identified a statistically significant reduction in the number of VTE risk assessments completed within 4 hours when the patient was clerked by a doctor, as compared to an ACP (OR 0.57, 95% CI 0.35–0.95, P=0.03). Therefore, ACPs contributed to more VTE risk assessments being completed within 4 hours and contributed to the national VTE CQUIN goal (Nuffield Trust, 2023).

Acute kidney injury risk assessment

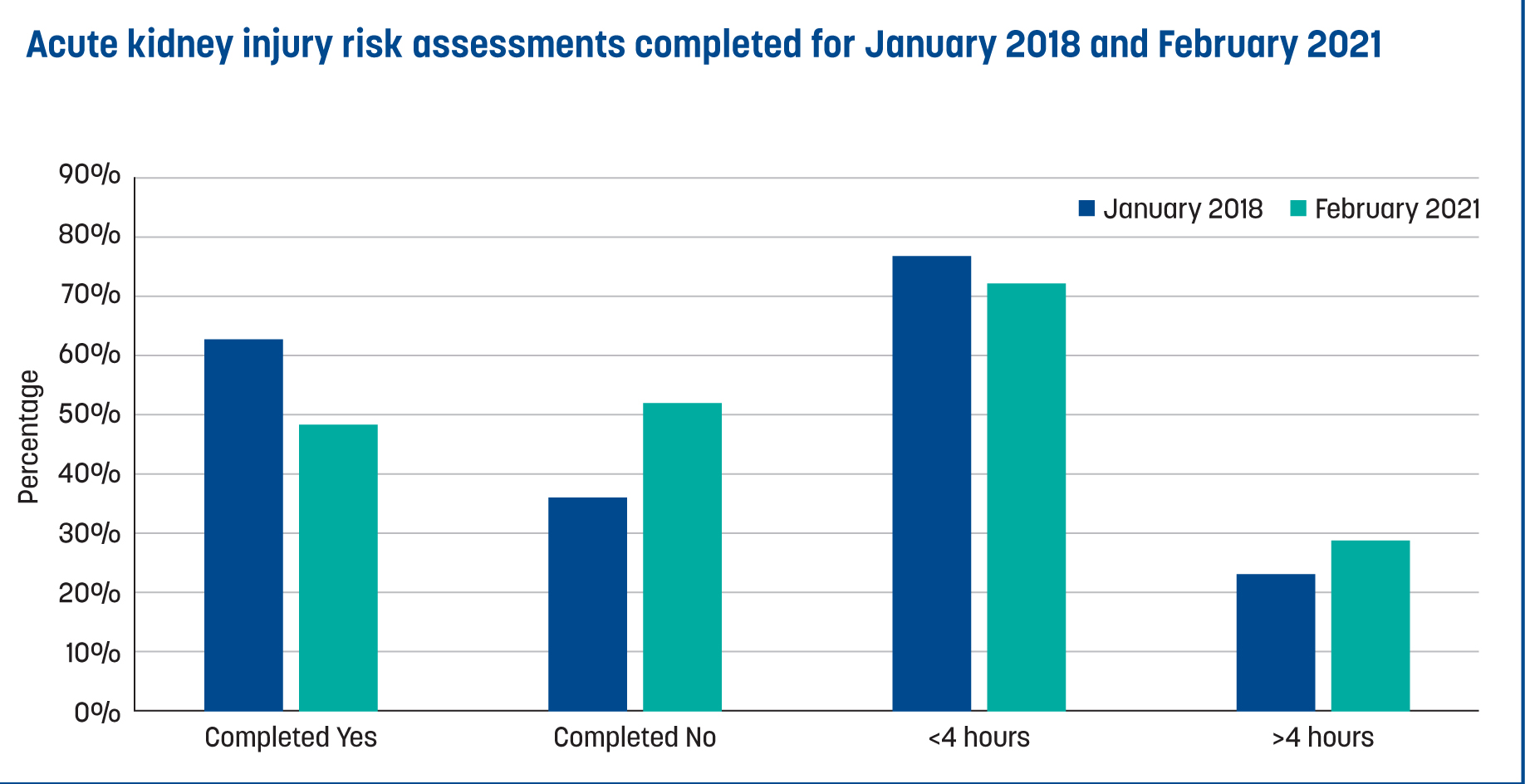

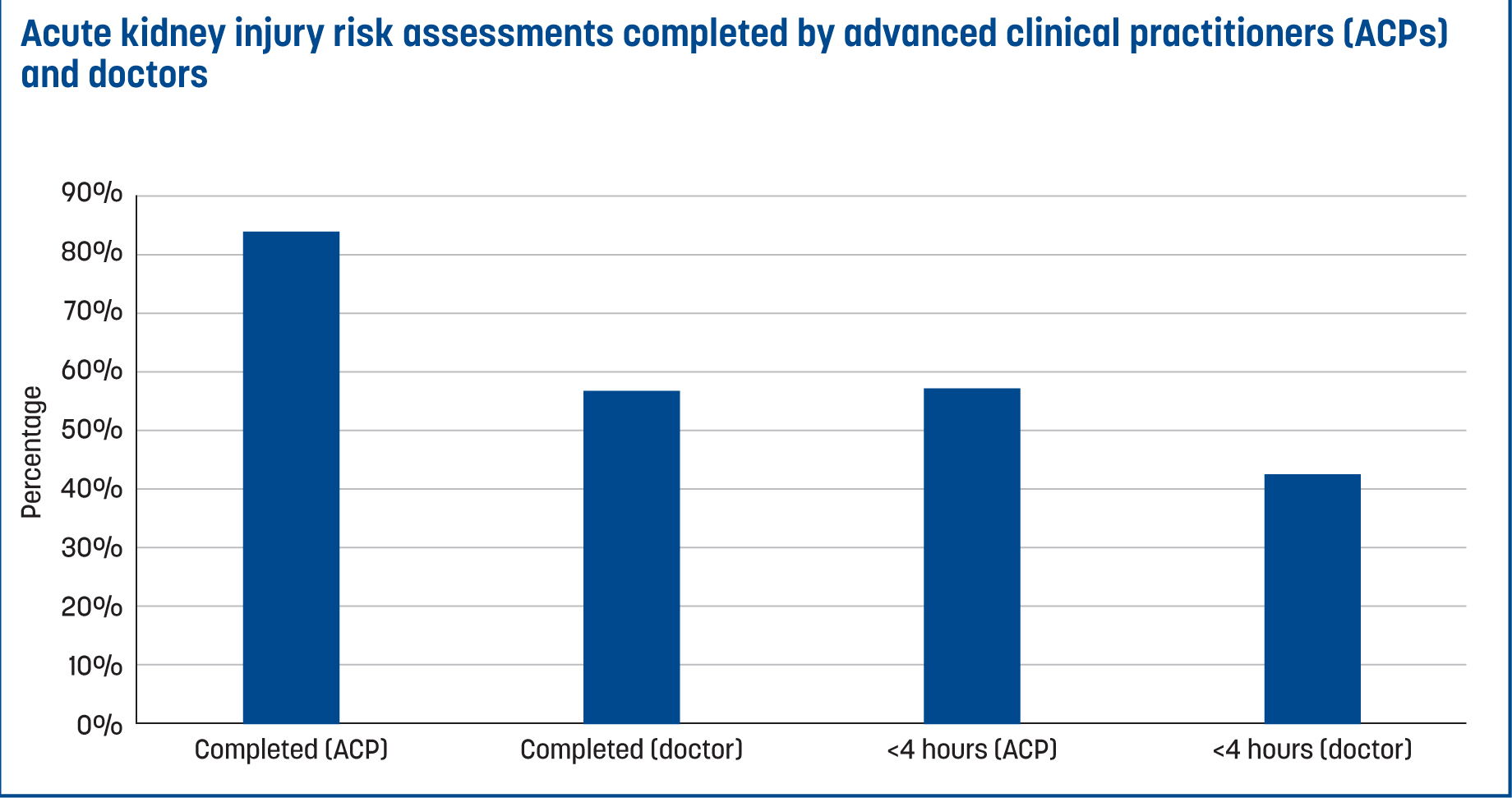

Of the 842 general surgical patients assessed by the SAU in January 2018, 537 patients (64%) had their risk of AKI assessed, of which 413 (77%) were assessed within 4 hours (Figure 3). In comparison, 275 (49%) of the 557 general surgical patients assessed by the SAU in February 2021 had their risk of AKI assessed with 195 (71%) of those assessed within 4 hours (Figure 3). The mean time taken to complete an AKI risk assessment was 283 minutes in January 2018, compared to 363 minutes in February 2021. When the patient was clerked by an ACP, 83% of AKI risk assessments were completed, with 58% being completed within 4 hours.

This compared to 57% of AKI risk assessments completed and 43% within 4 hours when the patient was clerked by a doctor (Figure 4). The analysed data identified a statistically significant reduction in AKI risk assessments completed within 4 hours when the patient was clerked by a doctor rather than an ACP (OR 0.54, 95% CI 0.33-0.89, P=0.02). Therefore, ACPs contributed to more AKI risk assessments being completed within 4 hours of attending the SAU.

Discussion

This study evaluated the current service provision within an acute general surgical setting to identify whether the introduction of ACPs within the EST improved national quality standards and patient care. Locally, a VTE and AKI risk assessment must be completed when a patient begins hospital care. Analysis of the results and the use of logistical regression identified a relationship between the clerking clinician and completion of the risk assessments, reflecting the clinician's individual contribution and direct impact on patient care. This quantitative retrospective longitudinal study found a statistically significant reduction in the number of VTE and AKI risk assessments completed within 4 hours when the patient was clerked by a doctor, rather than an ACP. Overall, ACPs contributed to more VTE and AKI risk assessments being completed within 4 hours of SAU attendance and contributed to the national VTE CQUIN goal (Nuffield Trust, 2023).

This study noted that ACPs as part of the EST improved and enhanced patient care. Pol-Castañeda et al (2022) also found significant improvements in clinical indicators related to pressure ulcer prevention and treatment, and vascular access care when inpatients were cared for by an ACP in three Spanish hospitals.

Globally, ACPs are healthcare professionals from a variety of professional backgrounds and are included in clinical departments depending on service needs. Therefore, ACPs not only have diverse levels of experience, knowledge and skillsets but are also trained to meet local specialist service requirements. In the UK, while ACPs adhere to local regulation and legislation, the title is not protected or regulated by an overarching governing body. Other countries are regulating advanced practice to protect the title, adopt uniformity and benefit healthcare systems (Wheeler et al, 2022; Haney, 2023). Doctors are concerned about the risk of litigation when ACPs take on tasks that were previously performed only by doctors (Williams, 2017; Hooks and Walker, 2020). Moreover, the ACP role has met with disparaging opinions and negative scrutiny, particularly on social media. While all healthcare professionals are required to work within their professional standards and have a legal obligation to comply with guidelines, protocols and policies, there is a possibility that some ACPs are practising with increased fear of litigation, a recognised influential factor in medical decision making. Evidence indicates that decisions and behaviours are not always deliberate or rational, but automatic and are profoundly influenced by the environment (Elaraby et al, 2023).

However, there are important benefits of using ACPs. They are experienced healthcare clinicians practising at advanced levels and are employed in clinical departments as permanent members of multidisciplinary teams and ESTs. This compares favourably to doctors who rotate between specialities and trusts, requiring a period of training. Therefore, ACPs have greater familiarity with healthcare systems, pathways and procedures, resulting in greater adherence to targets and guidelines (Hooks and Walker, 2020; Htay and Whitehead, 2021; Pol-Castañeda et al, 2022). It is for these reasons that ACPs are consistently employed for the induction and teaching of junior doctors.

The United Nations (2024) is working towards achieving universal health coverage by 2030 in that all individuals receive needed health services without suffering economic hardship. However, the World Health Organization (2024) estimated a projected shortfall of 10 million healthcare workers by 2030 with difficulties in education, employment, deployment, retention and performance. ACPs make a significant contribution to high-quality, effective and efficient patient care worldwide. However, significant challenges persist around regulation, consistency of role and public perception. All stakeholders must recognise and address these challenges in order to provide a thriving workforce that can be part of the solution for achieving universal access to health services.

Implications for practice

VTEs and AKIs continue to be global health burdens, resulting in significant mortality rates annually. Quality standards set out by NICE aim to improve the quality of care provided within health services. General surgical departments should consider integrating an adaptive and responsive workforce by enlisting ACPs as part of the extended surgical team.

Limitations

A sample size calculation was not performed before data collection, which would have determined the sample size required to test the hypothesis. It was initially intended that 3 months of data would be collected for each outcome variable. However, data collection was time limited and only 1 month was achieved for each period, resulting in 1399 cases. To reduce the risk of sampling errors, probability levels and CIs were used. A P value <0.05 was regarded as statistically significant, which reduced the risk of making a type 1 error and rejecting a correct hypothesis. To reduce the risk of type2 errors and accepting an incorrect hypothesis, a 95% CI was used, which resulted in the probability of inferring a statistically significant effect, if there was one.

The study design was noted to be slightly flawed during data collection. Secondary data were obtained retrospectively from medical records, which reduced bias by not disrupting clinical practice or influencing the actions of the doctors or ACPs being observed. However, 81 cases either had no hospital number recorded, an incorrect hospital number recorded or no encounter recorded, demonstrating a design bias that resulted in a reduction of the available sample size, which potentially influenced internal validity or data quality.

Conclusions

Working restrictions and a growing, ageing and sicker population have put tremendous pressure on surgical service delivery and patient care. This has prompted global healthcare reforms and fuelled a surge of new advanced healthcare roles, trained to undertake duties that were traditionally only performed by doctors. This has also led to the transformation of surgical teams into ESTs in the UK. This study used a quantitative retrospective longitudinal design to evaluate the value of ACPs within the EST in acute general surgical setting. The study found that ACPs significantly increased the number of VTE and AKI risk assessments completed within 4 hours of attending the SAU and admission to the hospital, improving the quality of patient care and contributing to a higher-quality VTE prevention service.

The findings support the current but limited field of study and the idea that ACPs add value to clinical departments. However, the findings are only applicable to the EST examined. In the UK, the lack of title protection and overarching governing body results in differences in role implementation and development, as well as poor understanding of ACP roles and boundaries. Further research is required to investigate the impact of ACPs working in ESTs on clinical outcomes, patient safety and interprofessional relationships on a national level, to aid transferability and generalisability as well as role integration.